“Antitrust is a kitchen table issue.” So said Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter in a speech provided below that included a discussion of moats and the importance of protecting competitive markets. However: “We’re often up against companies and firms with multiples of the lawyers and economists and paralegals and staff that we have.” Ouch. So said Kanter at the 2024 Stigler Center Antitrust and Competition Conference interview reported by ProMarket on 5.11.2024. ProMarket also stated that Congress has cut Kanter’s antitrust division’s budget by some 20 percent. Ouch again. There is much more, including the significance of what Kanter called “HIPS” as their tool for deciding what cases to take and thus its importance to manufactured housing and the U.S. economy. MHProNews has observed via various reports with analysis that the Biden regime was unlikely to be as serious about antitrust enforcement as their often-vigorous rhetoric might suggest. No special insider knowledge was needed to make that observation, because it is simply a matter of human nature. For instance. It is not typical for politicians to bite the hands that feed their campaigns or make a campaign successful. Perhaps the last president of the United States who accepted the help of what might be described as a special interest and then turned on it was the late President John F. “Jack” Kennedy (D). As left-leaning Bing’s AI powered Copilot observed: “After taking office, Kennedy and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, did pursue anti-organized crime efforts, which may have caused tensions with those who had supported them during the campaign2.” Be it coincidental or not, Kennedy was widely reported to be killed via an assassination plot in Dealy Plaza in Dallas, TX, and some have speculated that organized crime may have played a role in a scheme to kill Kennedy. Organized labor and organized crime – often intertwined in places such as Chicagoland – were said to play a key role in Kennedy winning a tightly contested election in 1960. A possible takeaway or point, with respect to Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, is that people who go to the White House don’t normally turn on their financiers and benefactors. More specific to Kanter or the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) chair Lina Khan and their campaign on behalf of competition, some of the high-profile antitrust cases being handled by the federal government in recent years were launched during the Trump era. That said, Kanter’s speech and the interview that follow provide relevant insights that he asserts reflects a ‘growing bipartisan consensus’ – meaning from both Democrats and Republicans – on the importance of antitrust enforcement.

Restated, it should be kept in mind that despite years of tough talk by higher profile Democrats like Senators Elizabeth Warren (MA-D) or Amy Klobuchar (MN-D) on how vigorous their antitrust efforts would be once they (Democrats) held power, there is an evidence-based argument to be made that their proverbial bark was worse than their bite. More on that in Part IV further below.

But first up in Part I is a reminder of key paragraphs from the Biden-Harris (i.e.: Democratic) “Fact Sheet” on competition had to say.

Part II is from an interview on the University of Chicago-linked ProMarket interview with Kanter from which some pull quotes above are from. Note that ProMarket’s about us page says: “Stigler Center for the Study of the Economy and the State at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.”

Part III is by Kanter in a different address found on the DOJ Antitrust website, that happened to be delivered at the Stigler Center.

Part IV is our focused analysis on those topics and possible insights or lessons for MHVille and the U.S.A. on the issue of monopolization and antitrust enforcement more broadly.

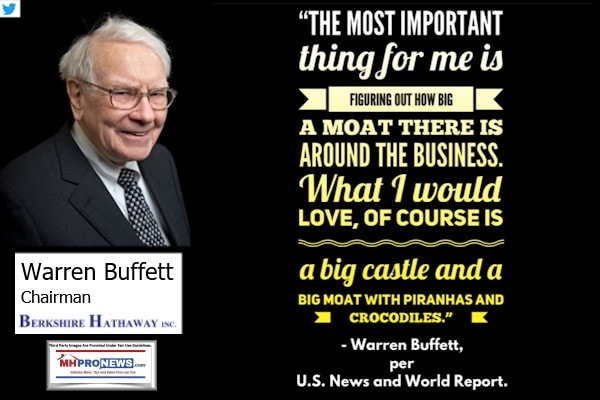

As a housekeeping note, in each of the items that follow highlighting is added by MHProNews. For new as well as regular visitors, highlighting should not stop a reader from carefully read all of the text that follows by skimming mainly highlighted items. While we are Buffett critics, and note that Buffett and moats will be part of the discussion in Part IV because Kanter raised the subject of moats below, we believe that Buffett is arguably correct on the high value of reading with care. Because, paraphrasing Buffett, knowledge is gained somewhat similar to how compound interest is earned on an investment.

Or as Matthew Kelly, popular author and business consultant put it, “Superficiality is the curse of the modern world.” At MHProNews we strive to eschew the superficial, to focus on topics that matter, and to provide a level of detail that may ultimately save readers time because they are digesting content on topics that matter in their lives today and could be impactful for years to come.

Part I

From the Biden-Harris era JULY 09, 2021 “FACT SHEET: Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy” is the following.

That lack of competition drives up prices for consumers. As fewer large players have controlled more of the market, mark-ups (charges over cost) have tripled. Families are paying higher prices for necessities—things like prescription drugs, hearing aids, and internet service.

Barriers to competition are also driving down wages for workers. When there are only a few employers in town, workers have less opportunity to bargain for a higher wage and to demand dignity and respect in the workplace. In fact, research shows that industry consolidation is decreasing advertised wages by as much as 17%. Tens of millions of Americans—including those working in construction and retail—are required to sign non-compete agreements as a condition of getting a job, which makes it harder for them to switch to better-paying options.

In total, higher prices and lower wages caused by lack of competition are now estimated to cost the median American household $5,000 per year.

Inadequate competition holds back economic growth and innovation. The rate of new business formation has fallen by almost 50% since the 1970s as large businesses make it harder for Americans with good ideas to break into markets. There are fewer opportunities for existing small and independent businesses to access markets and earn a fair return. Economists find that as competition declines, productivity growth slows, business investment and innovation decline, and income, wealth, and racial inequality widen. …”

Much of that is arguably accurate. The problem, for the economy and those who are suffering the effects of restricted competition, is that merely identifying the issue is not the same as dealing with those issues in a straightforward fashion. There are several remarks before and after those quoted above that might be called posturing mixed with paltering. Half-truths seem to be a common fuel used to keep ‘a base’ of voters and special interests satisfied while politicos go about doing what they authentically intend to do.

Part II – From ProMarket’s Interview with DOJ’s Kanter.

ProMarket: I’d like to ask you how you choose your cases? …”

Jonathan Kanter: We have to cover the entire economy. So we have a lot on our shoulders. And we have limited resources. So we developed a methodology that I call “HIPS,” like hands on our hips. It stands for “high impact programmatically significant.” What the concept is, when we’re deciding where to devote our resources, whether it’s an investigation or litigation, we think about, okay, what are the issues that would have the biggest impact on society. An impact can be measured in terms of economic harm, it can be measured in the importance of the product or service, it can be measured in its significance to society broadly. We try to make sure that we are focusing on things that have high impact. Programmatically significant—the “P” and “S” stand for programmatically significant—those are cases that might help focus on an important legal principle or important precedent that can shape enforcement going forward. We think about, very broadly speaking, our program through that lens, and then we use it to help determine how best to focus. Within that process, we have a methodology for allocating our resources in a way that we think is in the best interest of the public.

ProMarket: Earlier today in his keynote, Randy Picker argued that the Agencies should settle more cases. …”

Kanter: I think we have to look at each case on its own merits. And, you know, we are interested, always interested in bringing cases to a resolution. And sometimes that can be a negotiated resolution. Sometimes that can be litigation to an order. Ultimately, we’re interested in protecting competition. And so, however we can get there, we’ll get there. If we can do it efficiently, and companies are willing to go willingly, then that’s great. But that’s not always the case.

ProMarket: “…Last month, Congress cut 20% of the Antitrust Division’s budget as part of its Fiscal Year 2024 Appropriations Minibus. Would you say the wind is still to your back? What has changed, if anything? What is missing for a truly bipartisan coalition that supports antitrust?”

Kanter: I think that there’s still a tremendous amount of bipartisan support. We hear from folks across the political continuum, who are supportive of our work, who think that it’s important to protect the ability of farmers to get a fair return on investment from their livestock or physicians and nurses to have the ability to care for their patients—for competition, and the flow of information, and distribution of ideas. We hear from a wide variety of stakeholders. And support, I think it really does cut across the entire political continuum. So that hasn’t changed since our last discussion.

ProMarket: How do you anticipate the budget cuts impacting ongoing and future investigations and lawsuits?

Kanter: Well, the Antitrust Division is a formidable group of people. I would never bet against the Division. We will use the resources that we have as effectively as we can. I am proud of the work that we’re doing. We’re often up against companies and firms with multiples of the lawyers and economists and paralegals and staff that we have. But I think we are extraordinarily effective. And we, you know, more than hold our own against teams that are ten times the size.

ProMarket: Last summer…Much of the debate pivoted on a defense of the consumer welfare standard (CWS)—which by most definitions prioritizes consumer prices, output, innovation, quality, or variety—versus a shift toward “protecting competition,” which to me is about maintaining freedom of choice in the marketplace and encouraging creative destruction and the market entry of new firms. Relatedly, it’s about the dispersal of market power. Some of the critics of the “protecting competition” model argue that competition is not a goal in itself but an avenue to achieving traditional CWS goals. Thus, we should just keep the focus on the CWS. How would you defend the shift toward “protecting competition” against this argument?

Kanter: Well, it’s not a shift. It’s adhering to the language of the statute, which talks about substantial lessening of competition as tending to create a monopoly. There’s no mention of consumer welfare in the Clayton Act, but there is a mention of competition. And so the value that Congress sought to protect, the value judgment Congress made, was competition, the competitive process. Now, that can lead to all sorts of benefits, including the welfare of consumers, including innovation, including the welfare of workers. But Congress, in its wisdom, determined that concentration of power, whether it’s lessening of competition or tending to create a monopoly, is something important and worth protecting. And so I think our revised 2023 Merger Guidelines are more faithful to the language of the Clayton Act and more faithful to the history of antitrust laws and over a century of [court] precedent.

ProMarket: Another critique that arose during the symposium was that the new Merger Guidelines try to do too much: it is not just defending the traditional goals of the consumer welfare standard, such as consumer prices, and less common goals such as labor wages, but also abstract principles such as liberty and democracy. Are there limits to antitrust and antitrust enforcement? How do we determine them?

Kanter: So, we’ve taken the approach that competition and the process of competitive process, rivalry, and concentration of power is what we are asked to protect under the Clayton Act. At the Department of Justice, that’s what we focus on with respect to mergers: competition. Congress decided to protect competition because it has a wide range of benefits. And those benefits can include lower prices. Congress believed that dispersion of power can affect liberty and freedom and democracy. I think those are legitimate goals. So we preserve competition in order to protect all those attendant values and benefits.”

Part III

Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter Delivers Keynote at the University of Chicago Stigler Center

Thursday, April 21, 2022

Location

Chicago, IL

United States

Antitrust Enforcement: The Road to Recovery

Remarks as Prepared for Delivery

- Introduction

It is wonderful to be back at the Stigler Center. Five years ago, I attended the Center’s inaugural antitrust and competition conference. That first conference asked an important question: “Is There a Concentration Problem in America?” In retrospect, that particular conference functioned as a critical inflection point in the conversation regarding corporate concentration and the state of antitrust enforcement — a conversation that we are still having today, but against the backdrop of a dramatically different enforcement and political environment.

I have vivid memories of attending a lunchtime keynote, much like this one, where Judge Richard Posner quipped with a degree of seriousness and a bit of humor: “antitrust is dead, isn’t it?”[1] It was a provocative statement, to be sure, but a fair question. Judge Posner was saying the quiet part out loud. Indeed, the purpose of the conference was, in many ways, to assess whether antitrust enforcement still had a pulse and whether it could be nursed back to health.

It turns out that antitrust was not actually dead. If anything, the patient was on the table for open heart surgery.

I am pleased to report that the patient is alive and well, and the prognosis is good. Antitrust enforcement is on the mend, cared for and supported by a broad, bipartisan coalition devoted to its rehabilitation and full recovery.

We are not completely out of the woods yet though. Now we have the distinct challenge — and opportunity — of charting the path forward.

The good news is: that which does not kill us makes us stronger. And I am here to declare that the era of lax enforcement is over, and the new era of vigorous and effective antitrust law enforcement has begun. But the path will not be easy or linear.

- Five Point Plan for Antitrust Law Enforcement Amidst a Competition Crisis

With the remainder of my time today, I would like to outline what I see as five pillars of an effective civil antitrust enforcement regime. Although I am heartened by the productive discussions taking place in Congress to clarify our antitrust laws, Americans cannot afford to wait for new legislation to combat our competition crisis. These five pillars, which are by no means exhaustive, focus on enforcing the laws we already have — as Congress wrote them and as courts have interpreted them for decades.

First, recognize that the purpose of antitrust law is to protect competition.

Second, change the language of antitrust so it empowers all Americans to participate.

Third, adapt antitrust to address market realities rather than relying on static models and assumptions.

Fourth, revive enforcement of Section 2 of the Sherman Act.

Fifth, litigate cases to decisions so that the law can develop.

Each of these five pillars are worthy of longer discussion, so today I will just summarize briefly in the interest of time.

- The Purpose of Antitrust Is to Protect Competition

The first pillar is to recognize that the purpose of antitrust law is to protect competition. “The heart of our national economic policy,” the Supreme Court said in Standard Oil v. FTC, “long has been faith in the value of competition.”[2]

Yet somewhere along the way, the antitrust community lost its North Star. Over time, antitrust enforcement turned into a mathematical exercise focused on measuring welfare tradeoffs rather than trusting in the benefits of competition. We took up the impossible challenge of quantifying often unquantifiable welfare effects and speculative efficiencies down to the last decimal point. On the basis of those calculations and projections, the antitrust community took it upon themselves to decide who should win and lose rather than allowing competition and competitive markets to govern that determination.

The problem is that standards about measuring welfare tradeoffs turn antitrust into a narrow technical exercise that overlooks the realities of our economy. Antitrust law is about so much more. To paraphrase the Supreme Court in Northern Pacific, antitrust promotes material progress, quality, and innovation, “at the same time” that it supports our democracy and preserves a society of choice and opportunity.[3] Antitrust helps make us both prosperous and free.

We usually cannot measure and quantify all of those values. But we can promote them the way Congress intended — by protecting competition and the competitive process.

Instead, however, for years scholars and pundits have expended enormous energy debating the meaning of words that do not appear in the statute: the ephemeral “consumer welfare standard.”[4] By my count, 831 academic articles have been written invoking the consumer welfare standard, with more than 200 since 2020. It is the academic gift that keeps on giving.

All of this is fine as an intellectual exercise, but there is just one problem — the phrase “consumer welfare standard” does not appear in any statute, legislative history, or common-law precedents. The vibrant debate around the consumer welfare standard is an attempt to interpret words that are not in the law. Instead, the text of the antitrust laws reflects a value judgment by Congress to protect competition.

For generations, Congress has continued to anchor our antitrust laws in a simple but powerful concept: that competition deserves protection. Congress prohibited agreements that restrain trade, mergers that substantially lessen competition and conduct that monopolizes markets. Where the Sherman Act’s prohibition on unreasonable restraints of trade was general, the Supreme Court explained that, based on the common law it invoked, it outlawed restraints that were “unreasonably restrictive of competitive conditions.”[5]

The Supreme Court describes antitrust law the same way. There are zero Supreme Court opinions that use the phrase “consumer welfare standard.” Instead, the Supreme Court has repeatedly described the purpose of the antitrust laws as protecting competition. For each of the handful of times the Supreme Court has mentioned that antitrust is a prescription for consumer welfare, it has a dozen times reminded us that the mandate of the law is competition.[6] Even when courts mention the welfare of consumers as a prescription, they do not declare it as the exclusive goal. Indeed, courts have articulated myriad benefits and goals associated with preserving competition and enforcement of the antitrust laws.

Competition is the process of rivalry we all see play out in the markets and participate in every single day as buyers, sellers, workers and innovators.

Focusing on rivalry and competition lets us decide the tough questions in particular cases as markets evolve.

I have seen those that say antitrust does not protect our democracy argue that, even though that was plainly Congress’ intent, acknowledging that value in the law would not be administrable in particular cases. I would say the same for assessing the allocative efficiency impacts of particular cases. We spend millions arguing about models of the economy and how conduct will hypothetically shift outcomes to the fourth decimal point up or down. Plaintiffs and defendants offer experts to present quantitative models. More often than not, courts reject both competing models and do not believe either side. The judges are on to something. Law enforcers and courts are not central planners capable of consistently making those kinds of measurements. Calculating welfare effects is difficult in non-dynamic markets and is increasingly impossible in today’s multisided, cross-subsidized, and dynamic markets.

We can, however, more easily assess how conduct or mergers impact competition and the competitive process. That is how the antitrust laws simultaneously serve prosperity and freedom and all their many values — by preserving economic liberty and letting competition operate to organize our economy.

That is not to say promoting competition never raises tough questions and never requires debate and expertise. Of course, there will always be hard issues and hard cases. Focusing on competition, however, ensures that we remain faithful to the underlying purpose of the antitrust laws, which is that a competitive economy yields innumerable benefits for a free, open and democratic society.

Congress has chosen the values we are to preserve, and it has squarely settled on upholding a competitive process in free markets. Our job is to ensure a fair game, not to choose who wins.

The good news is that promoting competition can be administrable and effective. That is why it is the first pillar in addressing the competition crisis. We need to enforce the laws as we find them and vigorously protect competition as Congress demanded.

- Change the Language of Antitrust So It Empowers Americans to Participate

That brings me to my second pillar. For too long we have cloaked the antitrust laws in technocratic language. We must use the language of the people and the markets to empower participation in the Antitrust enterprise.

Our competition crisis affects real people. These people are not numbers in a spreadsheet. They are farmers struggling to find competitive buyers for their livestock. They are travelers who cannot afford a plane ticket home to visit family, or consumers who have little choice in who extracts and exploits their data.

When we issue guidelines and speak only of small but significant non-transitory increases in price, or of how vertical effects derive from the elimination of double marginalization, we exclude these people from the antitrust dialogue. This language boxes the public and the courts out of a critical discourse about how their economy is structured.

The technocratic veil around antitrust has helped mask contortions in the law that undermine its purposes. How else can one rationalize a theory that monopolies and competition can coexist? Or that establishment and maintenance of monopoly power are consistent with antitrust law? Using the language of the law and of real people we can be clear — merger to monopoly always lessens competition.

At the same time, a technocratic approach has made antitrust less accessible, and less democratically accountable. Congress, the courts and the people cannot engage with language that is accessible by a small segment of the population. Shielding the antitrust exercise from the public benefits only those with the money and power to hire experts and purchase access. And it shuts out other forms of expertise and real-world experience.

Finally, our inaccessible antitrust system makes it harder for businesses to understand whether their conduct is lawful. Antitrust is supposed to empower businesses to operate to their fullest potential in an economy free from the threat of monopolists. But businesses cannot act confidently if they do not know the rules or if the rules are so complex that it is impossible to rely on them with any degree of certainty.

Of course, economics remains incredibly important. So do other forms of expertise.

But at the same time, you should not need a graduate degree in economics to understand the law. The challenge before us is to engage in sound reasoning at the same time that we reengage the public with critical decisions that impact the structure of their economy.

That is why one of my primary goals as Assistant Attorney General is implementing the division’s Access to Antitrust Justice initiative — “AT2J.” That means listening to the public. That also means writing our guidelines in language that reflects how people understand harm to competition. We recently published an updated leniency policy and extended FAQ that reflect this focus on accessibility. Our ongoing review of the merger guidelines with the FTC is also placing a high priority on accessibility, both by engaging the public more broadly in the debate, and by prioritizing plain language in the revisions.

- Address Today’s Market Realities, Not Yesterday’s

The third pillar is to focus on the competitive realities of today’s markets. The digital revolution has brought about change in our economy rivaling, if not exceeding, that of the Industrial Revolution. We must acknowledge that new market realities demand new approaches to competition enforcement. We need to update our tools to meet the facts, not try to contort the facts to fit out of date tools.

The changes in our economy are not confined to digital markets. The internet revolution, the advent of Big Data, and the new ubiquity of connectivity have transformed our entire economy, from finance to healthcare to energy to retail and so on. Now you order your ticket online in advance, interacting in seconds with a dozen or more interconnected businesses. Across the economy, businesses are harvesting more data, gatekeepers are growing in strength and automated decision-making is changing business paradigms. Just as our economy evolves, so must the tools that we use to understand it.

That will often mean focusing first on the facts when we examine competitive realities, as opposed to beginning with assumptions embedded in out of date models or cases. We need to start with how competition really works in a market, then extrapolate to whether competition would be harmed or a monopoly created or maintained.

It will also mean reassessing whether precedents are outdated because they reflect embedded assumptions about how markets work that no longer hold true. As Justice Gorsuch recently explained in NCAA v. Alston, analysis of competitive effects follows market realities, and so “[i]f those market realities change, so may the legal analysis.” [7] While enforcers and the courts must respect Congress’ core command that the antitrust laws should be applied to protect competition, how we do that must evolve as competitive realities do.[8]

Antitrust enforcers must therefore think critically about where their practices, and the cases, reflect outdated assumptions.

Take Brooke Group.[9] There, the Supreme Court recognized a safe harbor for above-cost pricing, even where such pricing is exclusionary, based upon what it characterized as “the general implausibility of predatory pricing.”[10]

A growing body of evidence suggests that above-cost pricing strategies can in fact be a rational strategy for anticompetitive exclusion, particularly in modern digital markets.[11] We need to think about whether an assumption of general implausibility still holds in modern markets when companies often prioritize long-term growth of share price over short-term profitability. Strategies that may have once seemed implausible or irrational can yield eye-popping wealth for executives that earn more from their shareholding than from salaries or bonuses.

Another example is the refusal to deal paradigm set forth in Trinko and Aspen.[12] Modern online platforms are cooperatives. They are fundamentally participatory in a way telephone lines and ski lifts never were. Yet Trinko relies on basic understandings about how networks are built and whose investment incentives are most important. If the nature of the networks changes, other parts of the analysis should probably follow.

There are more examples than I have time to go through today.

That is the third pillar: we need to focus on markets as they exist today. If conduct harms competition, the models and tools need to be adapted, not the other way around.

- Vigorously Enforce Section 2 of the Sherman Act

The fourth pillar of my plan is to vigorously enforce Section 2 of the Sherman Act.

Section 2 prohibits monopolization, but when we met here five years ago it was probably the best illustration of Judge Posner’s question. With no significant cases in nearly twenty years at that point, Section 2 was very near death.

Senator Sherman warned that “if the concentrated powers of [a monopoly] are entrusted to a single man, it is a kingly prerogative, inconsistent with our form of government.” Yet we now know many such people who enjoy power over key markets. Notwithstanding the original goals of the law, we saw the emergence of monarchs over the new industries of the digital revolution.

Senator Sherman wrote the antitrust laws as a prescription. We must vigorously enforce the Sherman Act to prevent the unlawful acquisition, maintenance and extension of monopoly power.

That means we must assess conduct on its merits, and based on the entire course of conduct involved. We need to use all our tools and understanding to assess how monopolies have arisen and how they are maintained. We must challenge conduct that suppresses or destroys competition.

We also need to take more seriously courses of conduct that maintain monopolies. I gave remarks on this point a couple weeks ago. Monopoly maintenance, in the form of moat-building strategies, helps to prevent the erosion of monopoly positions and thereby harms competition. Enforcers and courts need to do a better job of assessing the overall scheme of monopoly maintenance, including through acquisitions of nascent competitors and the threat of discrimination.

That is the fourth pillar — we must vigorously enforce Section 2 of the Sherman Act. It is a statute tailor made to meet the moment. We will not be afraid to challenge monopolization.

- Enforce the Law Through Litigation

The fifth pillar of my plan is to faithfully discharge the division’s affirmative “duty” to “prevent and restrain” antitrust violations.[13] Our duty is to litigate, not settle, unless a remedy fully prevents or restrains the violation. It is no secret that many settlements fail to preserve competition</span.. Even divestitures may not fully preserve competition across all its dimensions in dynamic markets. And too often partial divestitures ship assets to buyers like private equity firms who are incapable or uninterested in using them to their full potential.

At the Department of Justice, we are law enforcers. It is not our role to micromanage corporate decision making under elaborate consent decrees. It is our job to enforce the law. And when we have evidence that a defendant has violated the law, we will litigate to remedy the entire harm to competition. That will almost always mean seeking an injunction to stop the anticompetitive conduct or block an anticompetitive merger.

But my emphasis on litigation is not just about institutional competence. It also supports the goal of ensuring the language of antitrust reflects how people think about competition and in ensuring that the law catches up to market realities. If we do not bring cases, the law will stagnate. Even as our economy undergoes revolutionary change, over-reliance on settlement would leave us governed by yesterday’s law. We need to bring cases to enable the courts to wrestle with the realities of today’s markets and ensure antitrust law is fit for purpose in the modern economy. The failure of antitrust enforcers to enforce Section 2 of the Sherman Act has allowed the law to stagnate.

That is point five: litigate. Congress designed antitrust law to play out in the courts, before judges and juries in an open forum.

III. Conclusion

I want to end by reflecting on my duty. I swore an oath to uphold the laws. Just last week, I appeared before a federal court in Denver where I explained just how seriously I take my obligation to protect the American public under the antitrust laws. Antitrust is a kitchen table issue. The public depends on us to police the channels of commerce against collusion and monopoly. When we fail, families struggle to afford groceries. They earn lower wages. They lose control of their own private data to dominant platforms. The American Dream slips away.

That is why the Department of Justice must zealously protect competition. With a healthy diet, steady exercise and regular checkups, I have a feeling that the patient will continue to lead a long and healthy life. I look forward to the work ahead.

Thank you.

[1] Stigler Center, Judge Richard A. Posner in Conversation with Professor Luigi Zingales, YouTube, at 05:20 (Mar. 28, 2017), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JRCm_gJ2EOk.

[2] Standard Oil Co. v. FTC, 340 U.S. 231, 248 (1951).

[3] N. Pac. Ry. Co. v. United States, 356 U.S. 1, 4 (1958).

[4] See, e.g., Symposium, The Goals of Antitrust, 81 Fordham L. Rev. 2151 (2013).

[5] Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States, 221 U.S. 1, 58 (1911).

[6] Compare, e.g., Reiter v. Sonotone Corp., 442 U.S. 330, 343 (1979) (relying on Robert Bork, The Antitrust Paradox (1978), to describe antitrust as a “consumer welfare prescription” without describing it as exclusively so), with, e.g., NCAA v. Alston, 141 S. Ct. 2141, 2147 (2021) (“In the Sherman Act, Congress tasked courts with enforcing a policy of competition . . . .”), N.C. State Bd. of Dental Exam’rs v. FTC, 574 U.S. 494, 502 (2015) (Sherman Act “serves to promote robust competition” and prohibit “practices that undermine the free market”), Leegin Creative Leather Prods., Inc. v. PSKS, Inc., 551 U.S. 877, 895 (2007) (antitrust laws “designed primarily to protect interbrand competition”), State Oil Co. v. Khan, 522 U.S. 3, 15 (1997) (primary purpose of antitrust laws “is to protect interbrand competition”), Spectrum Sports, Inc. v. McQuillan, 506 U.S. 447, 458 (1993) (Sherman Act directed “against conduct which unfairly tends to destroy competition itself”), NCAA v. Bd. of Regents of the Univ. of Okla., 468 U.S. 85, 104 & n.27 (1984) (“Under the Sherman Act the criterion to be used in judging the validity of a restraint on trade is its impact on competition.”), Nat’l Soc’y of Pro. Eng’rs v. United States, 435 U.S. 679, 695 (1978) (Sherman Act reflects “legislative judgment” that “competition is the best method of allocating resources”), Gordon v. N.Y. Stock Exch., Inc., 422 U.S. 659, 689 (1975) (“sole aim of antitrust” is “to protect competition”), United States v. Topco Assocs., Inc., 405 U.S. 596, 610 (1972) (“freedom” guaranteed by antitrust “is the freedom to compete”), FTC v. Proctor & Gamble Co., 386 U.S. 568, 580 (efficiencies are no defense to anticompetitive merger because Congress “struck the balance in favor of protecting competition”), United States v. Von’s Grocery Co., 384 U.S. 270, 274–77 (1966) (purpose of antitrust laws is to “prevent economic concentration” and “protect competition”), United States v. Phila. Nat’l Bank, 374 U.S. 321, 362–63, 371–72 (1963) (“[C]ompetition is our fundamental national economic policy . . . .”), Brown Shoe v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 315–23 (1962) (Celler-Kefauver Act’s “dominant theme” to combat “rising tide of economic concentration” through competition), N. Pac. Ry. Co. v. United States, 356 U.S. 1, 4 (1958) (“[T]he policy unequivocally laid down by the [Sherman] Act is competition.”), United States v. E. I. du Pont de Nemours & Co., 351 U.S. 377, 385–86 (1956) (Sherman Act achieves “freedom of enterprise from monopoly or restraint”), Standard Oil Co. v. FTC, 340 U.S. 231, 248 (1951) (“The heart of our national economy policy long has been faith in the value of competition.”), Allen Bradley Co. v. Local Union No. 3, Int’l Bhd. of Elec. Workers, 325 U.S. 797, 809 (1945) (“The primary objective of all the Anti-trust legislation has been to preserve business competition and to proscribe business monopoly.”), and Bd. of Trade v. United States, 246 U.S. 231, 238 (1918) (restraints legal if they “regulat[e]” or “promote[] competition” but illegal if they “suppress” or “destroy” it). Bork’s selective reading of the legislative history to divine a “consumer welfare standard” has been widely criticized. See, e.g., Lina M. Khan, Note, Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox, 126 Yale L.J. 710, 720–21 (2017); Herbert Hovenkamp, The Antitrust Enterprise: Principle and Execution 39–42 (2005).

[7] NCAA v. Alston, 141 S. Ct. 2141, 2158 (2021).

[8] State Oil Co. v. Khan, 522 U.S. 3, 20 (1997).

[9] Brooke Grp. Ltd. v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 509 U.S. 209 (1993).

[10] Brooke Grp. Ltd. v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 509 U.S. 209, 223, 227 (1993); see also Matsushita Elec. Indus. Co. v. Zenith Radio Corp., 475 U.S. 574, 589 (1986) (“[T]here is a consensus among commentators that predatory pricing schemes are rarely tried, and even more rarely successful.”).

[11] Jonathan B. Baker, The Antitrust Paradigm: Restoring a Competitive Economy 147 & n.143, 148 & n.144 (collecting research).

[12] Verizon Commc’ns Inc. v. Law Offs. of Curtis V. Trinko, LLP, 540 U.S. 398 (2004); Aspen Skiing Co. v. Aspen Highlands Skiing Corp., 472 U.S. 585 (1985).

[13] 15 U.S.C. §§ 4, 9, 25. ##

Part IV – Additional Information with More MHProNews Analysis and Commentary

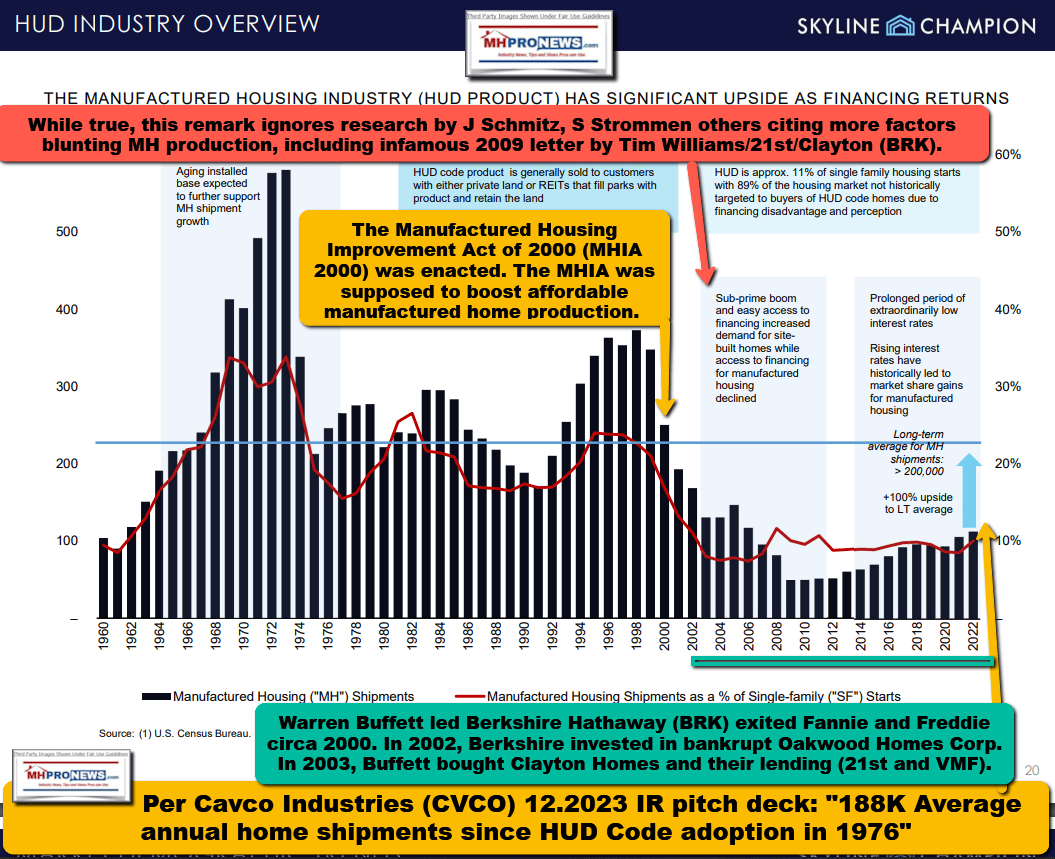

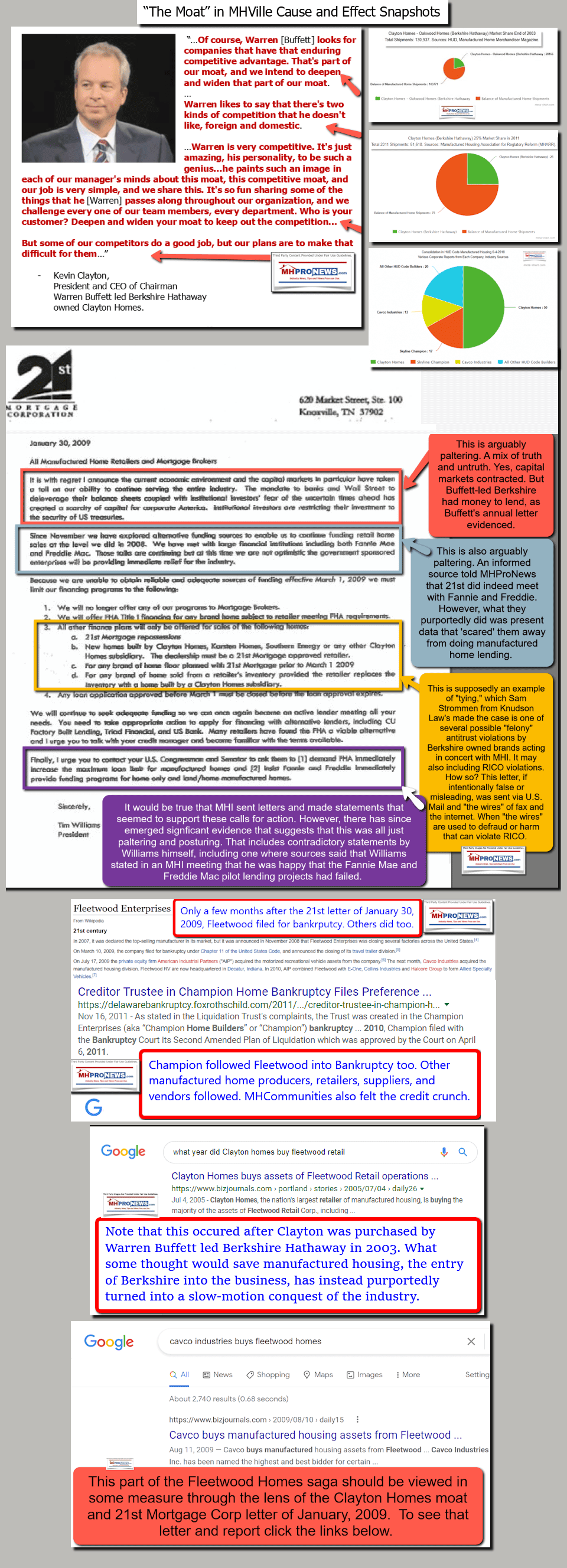

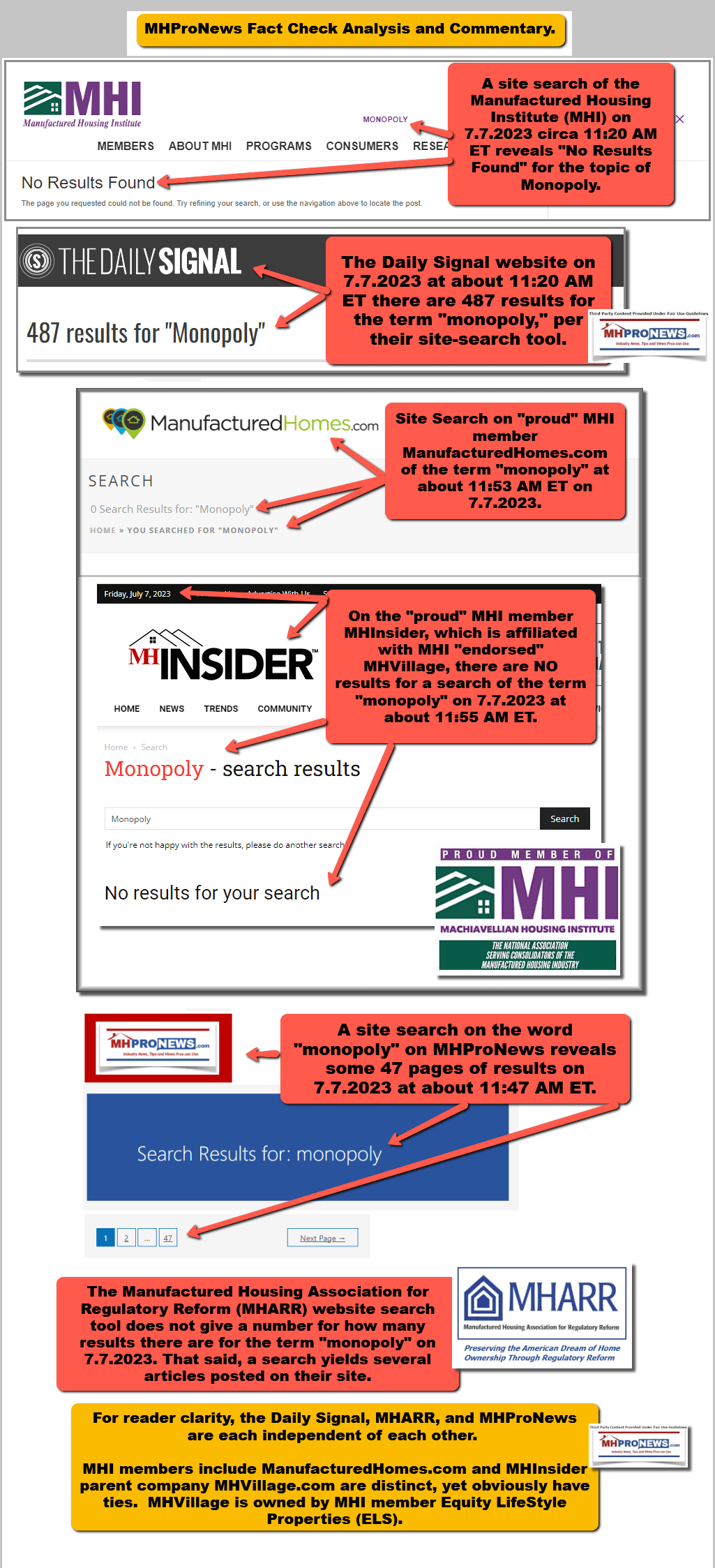

There is an evidence-based case to be made that antitrust or anti-monopoly (i.e.: pro-markets, pro-competition) law enforcement, or the lack thereof, are a critical 21st century issue in manufactured housing and beyond. For the better part of a decade, MHProNews has demonstrably provided the most content on the topic of antitrust, moat, and monopolization related issues of any trade publication, blogger, or trade group in the U.S. While that may sound impressive, the reality is that there are those in manufactured housing avoid the topic entirely, or they do so with a wink and a nod to advance the agenda of industry consolidation and moat-building. So, while our MHLivingNews sister-site and MHProNews are apparently the runaway leaders on these issues in manufactured housing, what may be more impressive is to note that our sites have more content – and more relevant content – on the subject of the harms caused by monopolization and failure to vigorously and routinely enforce antitrust law than all of our top trade rivals combined many times over.

In no particular order of importance are the following observations about the insights from Parts I-III above.

1) Some of Kanter’s statements could be encouraging to those in the industry who recognize that manufactured housing has been hobbled by purported antitrust violations. Note that MHProNews/MHLivingNews have referenced the work of economists at the Minneapolis Federal Reserve, who interestingly also have an item published on ProMarket that MHProNews has referenced previously.

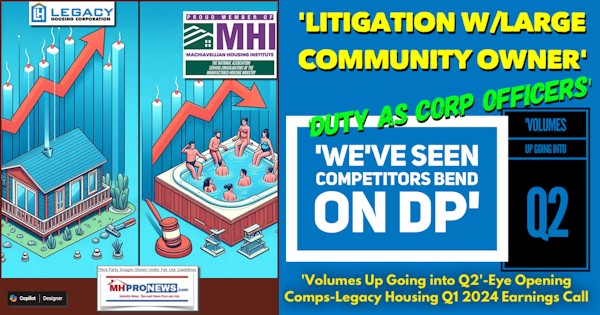

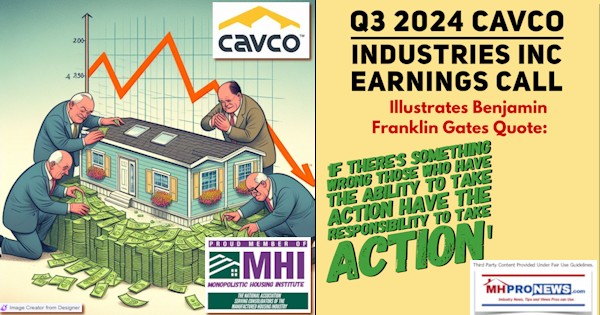

2) Another theme in recent years on our industry-leading trade platforms has been to note that people or organizations may say something with little or no intention to seriously achieve that goal that they are talking about, at least, not in the near future. For instance. There may come a day when the Manufactured Housing Institute (MHI) trademarked CrossModTM homes may begin to sell in meaningful numbers. But the known evidence clearly suggests that CrossMods were not intended to do what was claimed in their original and ongoing pitch. Namely, that it would broaden and expand the market for manufactured housing and increase acceptance of manufactured housing. That claim was arguably bogus and flawed from the outset. Time has proven our initial concerns (and in fairness, those issues raised on the MHI-backed ‘new class of homes‘ later rebranded as CrossMods in reports from the Manufactured Housing Association for Regulatory Reform or MHARR) about CrossMods proved to be accurate, while MHI and their so-called Big Three of Clayton Homes (BRK), Skyline Champion (SKY), Cavco Industries (CVCO) and MHI proved to be so wildly incorrect. How is it possible that the larger organizations with the deeper pockets bolstered by ‘consumer research’ and ‘focus groups’ (i.e.: MHI-Clayton-Skyline-Champion-Cavco) turned out to be so wrong? The evidence suggests that it was meant to be a sabotage monopoly tactic.

3) But before going to deeply into those weeds, let’s sift some wheat from the Biden-Harris chaff. There is, as Kanter remarked, a growing (at least verbalized) consensus on the importance of antitrust (a.k.a. pro-competition, anti-monopolization) laws. Among the reasons to do so is because healthy competition yields a range of good outcomes. While some could quibble over the price numbers, which keep changing due to Biden-Harris era inflation, they were broadly correct (see Part I) in saying that higher wages, lower prices, more opportunities, innovation, and selection are all a part of the fruits of healthy competition. Kanter, without specifically citing the statements provided in Part I, all but double downed on those notions. Kanter did so by saying that honoring the original intention of Congress in passing the Sherman and Clayton antitrust acts helps achieve a range of social, economic, political, pricing, labor- and competition-protecting outcomes. Kanter may not know that MHProNews/MHLivingNews exist, but odds are if he did, based on what he said above, he would be nodding in agreement with reports like those linked below.

4) Right or wrong, for decades there was a perception that Democrats were more antitrust focused, and Republicans were more about keeping antitrust efforts at bay. Perhaps a closer look at that notion through a careful historic lens might yield a different perception, because federal politicians (i.e.: Congress, presidents) raise or dodge issues that routinely reflect what their donors desire. Note that without explicitly saying that, Kanter implied it by saying that antitrust has been moribund for decades. Quoting Kanter:

It turns out that antitrust was not actually dead. If anything, the patient was on the table for open heart surgery.”

Open heart surgery is a life-or-death matter. If antitrust law is supposed to safeguard competition, Kanter’s remarks are a clear sign that this is life or death to thousands of businesses in or beyond manufactured housing. Kanter’s comments therefore ought to be as relevant to manufactured housing pros as those made by HUD researchers Pamela Blumenthal and Regina Gray.

Thus, the fact that MHInsider, ManufacturedHomes.com, MHReview, and others either downplay or entirely ignore the subject of the importance of monopolization and antitrust law enforcement is to our profession only illustrates how poorly they are serving the broader industry, but also illustrates that they are apparently serving the interests of those who DO NOT WANT CONSOLIDATION/MONOPOLIZATION to be a hot topic. While MHI is in this context the tool of the purported consolidators, and they do have what might be described as a fig-leaf ‘antitrust warning’ document, that is par for their course. Posturing, paltering, spin, and propaganda are part of the theatrics of attempting to deflect concerns from where they should be focused.

5) The health of the manufactured housing marketplace, if someone was to apply Kanter’s HIPS test, ought to be a high priority importance to the DOJ. Why? Because MHProNews has repeatedly as well as recently made the case that without millions of more new manufactured homes, the affordable housing crisis can’t be cured.

6) The courts have recognized that it isn’t just documents or statements that might bring a charge, conviction, or other victory in a legal matter. Behavior can be used to infer intention. It is useful that Kanter, irrespective if he was sincere or not, mentioned moats in his speech cited in Part III above. Let’s look again at what Kanter said in context.

Couple that with the following from Kanter.

That is why the Department of Justice must zealously protect competition.”

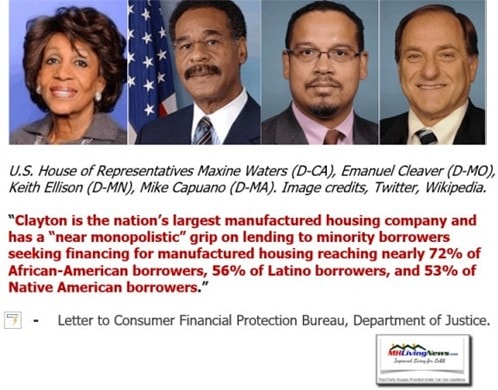

7) Note that MHProNews has reported that there were two sources, deemed reliable, that assert that during the Trump Administration and while Makan Delrahim was in Kanter’s role as the Assistant Attorney General for antitrust at DOJ, there was purportedly a meeting held to discuss a probe of manufactured housing, Clayton Homes, etc. A well-placed source in that department recently denied that in an off the record statement to MHProNews. But when pressed by saying two sources asserted that such a meeting occurred, that person pivoted. Even in the absence of sources that tell MHProNews that such a meeting of DOJ attorneys occurred to discuss manufactured housing, it should not be a surprise if it did. Why? Because Representative Maxine Waters (CA-D) and some of her Congressional colleagues said they made referrals to DOJ and the CFPB. That letter and a related report are linked below.

Flashback to Trump era…note the similar themes to Kanter’s remarks?

8) Then recall that MHProNews asked Donald Trump Jr. about the importance of antitrust enforcement. Without hesitation, the 45th president’s son answered in a front of rather partisan gathering in Orlando, FL that antitrust enforcement was the #2 or #3 issue facing the country.

9) Those who grasp the meaning and importance of God-given and Constitutionally protected rights understand and respect the ‘right to remain silent.’ The fact that MHI, their attorneys, and several of their corporate leaders have remained mute on these topics, despite repeated inquiries by MHProNews over the years is interesting. But under the law, they have that right. That said, one might think that if they had nothing to hide, they would not be busy hiding.

With that in mind, consider the following Q&As (chats) with Bing’s highly rated AI powered Copilot, noting that sources have said that this search tool has a left-leaning bias.

The Manufactured Housing Institute has been accused of being part of a process that is fostering consolidation in manufactured housing. Those allegations arise from sources inside and outside of manufactured housing. MHProNews/MHLivingNews have repeatedly asked them to respond to those concerns. In the past, Institute leaders used to respond readily to inquiries by those publications. But since they began pressing legal issues, is there any evidence you can find that either MHI senior staff, corporate board members, or their attorney(s) have publicly responded to allegations of antitrust or other collusive behaviors that purportedly are limiting manufactured housing and are fostering consolidation as a result? Link results.

> That is interesting, but there are apparent errors in the above, Copilot. Boyle is a spokesperson for MHI, not an attorney, isn’t that correct? Next, several reports on MHProNews document those outreaches to MHI leaders and attorneys, but no responses are reported, isn’t that also correct? More specifically, in any post, op-ed, or article that involves an MHI leader or attorney, can you find any evidence online that they have denied being involved in antitrust violations? And haven’t several antitrust civil suits been launched that feature several higher profile MHI member brands? Again, link results.