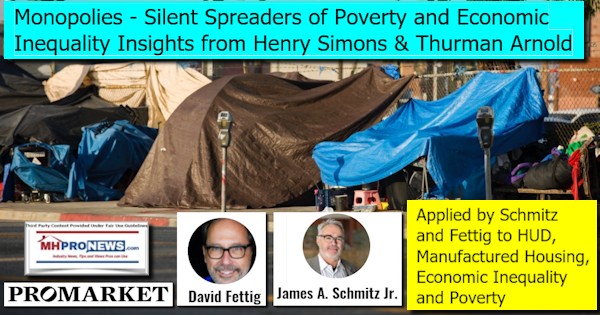

Stating the Obvious and reviewing the facts can bring clarity to long festering issues that may have vexed our society as well as our industry for decades. For an example is the issue of homelessness. It should go without saying that the less affordable housing is, the greater housing insecurity becomes, the odds for an event that triggers homelessness increases. For decades, federal, state, and local jurisdictions have battled homelessness by trying to provide temporary shelters. Issues such as alcoholism, drug addiction, various crimes are often associated with the homeless. These are true enough. But the obvious point out to be that avoiding housing insecurity is arguably the best way to avoid homelessness. The more economically stable some individual, household or family is, the less likely they are to be triggered by an event into homelessness. As this survey of facts and perspectives on homelessness will reveal, the cost on society for homelessness is staggering. It additionally should be measured by the various types of harm caused by allowing individuals to live in tents, cardboard boxes, other forms of makeshift structures. Before diving into this facts and analysis feature that precedes our MHProNews daily market report and headline recap, let us also note this point. People and organizations may provide accurate or mostly correct information, but might still offer a ‘solution’ that when objectively examined fails to solve the problem. It should also be obvious that this topic is being tackled on a manufactured housing trade news website precisely because it is an issue that our industry is well positioned to benefit others and honestly profit by being part of the solution.

As of 1.21.2021, what follows are some of the latest data from federal, nonprofits, and mainstream media sources. Our analysis and commentary will follow. This will be updated circa March/April when federal and other data sources should have their figures for 2021 collated and published.

On 3.18.2021, HUD released its 2020 Annual Homelessness Report. “2020 marks the first time since data collection began that more individuals experiencing homelessness were unsheltered than were sheltered,” stated HUD.

“The average life expectancy of a homeless person is just 50 years,” stared PolicyAdvice.net

“In January 2020, there were 580,466 people experiencing homelessness in America. Most were individuals (70 percent),” said EndHomelessness.org on 8.4.2021. The following trends and factual snapshots are from that source.

Aug 4, 2021 — In January 2020, there were 580,466 people experiencing homelessness in America. Most were individuals (70 percent), and the rest” are part of the breakdown that follows from EndHomelessness.org

State of Homelessness: 2021 Edition

The current report draws from the nationwide Point-in-Time Count that occurred in January of 2020, just a few weeks before COVID-19 was declared a national emergency. Thus, the data does not reflect any of the changes brought about by the crisis. Instead, the current report reflects the State of Homelessness in America just before a once-in-a-lifetime event interrupted the status quo.

The Basics

In January 2020, there were 580,466 people experiencing homelessness in America. Most were individuals (70 percent), and the rest were people living in families with children. They lived in every state and territory, and they reflected the diversity of our country.

Trends in Homelessness

Between 2019 and 2020, nationwide homelessness increased by two percent. This change marks the fourth straight year of incremental population growth. Previously, homelessness had primarily been on the decline, decreasing in eight of the nine years before the current trend began.

Locating Homelessness

Ending homeless is an ongoing challenge throughout America. However, the severity of the challenge varies by state and community. Locating the areas experiencing the most significant challenges, and directing additional attention and possibly new resources towards them, could result in meaningful reductions in homelessness. There are two ways two evaluate geographic variations—counts and rates.

Counts. Examining the jurisdictions with the largest homeless populations is informative. Many also have the highest populations, overall. For example, California is the most populous state in the union and also has the largest number of people experiencing homelessness. Similarly, the Continuums of Care (CoC) with the largest homeless populations include highly populous major cities (e.g., New York City, Los Angeles, and Seattle) and Balance of State CoCs encompassing numerous towns and cities.

Fifty-seven percent of people experiencing homelessness are in five states (California, New York, Florida, Texas, and Washington). Half are in the twenty-five CoCs.

Total Number of People Experiencing Homelessness per Year by Type, 2007–2020

State & CoC Ranking 2020

Homeless Assistance in America

Homeless Assistance Bed Inventory Trends, 2007-2020

State-by-State Trends in Homeless Assistance, 2007-2020

Indicators of Risk

Many Americans live in poverty, amounting to nearly 34 million people or 10.5 percent of the U.S. population. As a result, they struggle to afford necessities such as housing.

In 2019, 6.3 million Americans households experienced severe housing cost burden, which means they spent more than 50 percent of their income on housing. This marked the fifth straight year of decreases in the size of this group. However, the number of severely cost-burdened American households is still 10 percent higher than it was in 2007, the year the nation began monitoring homelessness data.

“Doubling up” (or sharing the housing of others for economic reasons) is another measure of housing hardship. In 2019, an estimated 3.7 million people were in these situations. Some doubled-up people and families have fragile relationships with their hosts or face other challenges in the home, putting them at risk of homelessness. Over the last six years, the number of doubled-up people has been trending downward but is 3 percent higher than in 2007.

Over a period lasting more than a decade, the nation has not made any real progress in reducing the number of Americans at risk of homelessness. In fact, these challenges are slightly worse. The trends lines in the above chart point to severe house cost and doubled-up numbers that are higher in 2019 than they were in 2007. Even more troubling is that available data predates the COVID-19 health and economic crisis. Reduced work hours and elevated unemployment during the recession may be increasing housing cost burdens and driving more people into doubled-up situations.

State-by-State Trends in Populations At-Risk of Homelessness, 2007-2019

Even before the pandemic, there was significant variation among the states in their data on people at risk of homelessness. National-level data, which has been discouraging, can mask even more dire challenges in specific areas of the country. For example, since 2007, severe-housing-cost burdened households grew by 35 percent in Hawaii and 36 percent in Connecticut (numbers that are even higher than national-level growths in these areas). Similarly, over that same time period, the number of people doubled up expanded by 102 percent in Idaho and 65 percent in Florida.

Complicating matters further, the impacts of the current recession and responsive policies have varied across the country. As a result, regional differences in at-risk housing factors could be shifting and changing.

Learn more about the cost to end homelessness in America, and get statistics about the problems unhoused populations face. According to the Department of Housing and Urban Development, it would cost $20 billion to end homelessness in the United States.” Apr 9, 2021

MHProNews Note: That claim by HUD appears to be a misstatement of some type. Why? Because there are sources that say that when all of the costs paid by public officials at the local, state, and national levels are tallied there is already some $20 billion a year being spent by government in connection to homelessness.

Insights from the Mile High City of Denver, CO

KDFR in a 2021 report some 6 months ago said “Denver metro spends at least double on each homeless person than it does for a K-12 student.” That same report stated that: “The Mile High City’s homelessness problem suffers from an absence of information. Homeless populations are hard to count. Social program funding sources are widespread with complex and shifting relationships. Counting the social programs spending or measuring success rates can be even harder.”

To underscore the “absence of information” notion. MHProNews, in organizing the data for this report, had to turn to multiple sources to gather this information. That may shed light on why there is more an absence of understanding than an “absence of information.” While there are obviously useful reports available, no one source seems to have gathered sufficient insights together in an fashion that can make informed analysis of the underlying causes and solutions possible. More on that shortly.

That same source stated:

- “The Denver metro spends just under a half billion dollars a year: $481 million.”

- “The Common Sense Institute estimates between $41,679 and $104,201 per year spent per person experiencing homelessness.”

- “For comparison, the median per capita income in Denver is about $45,000 and the median Denver household income $68,592 – meaning that even at the lower range of spending estimates the metro is spending the same amount per homeless person that the average Denverite makes in a year.”

- “Services to the homeless cost between two and five times more than the average Denverite pays in rent, as well, at $21,156 in annual rent.”

MHProNews Note. Accepting that information uncritically, at face value, begs numerous questions. Among them?

How is it possible that in an information age the best that the Common Sense Institute (no offense to them, as this appears to be a wider problem) is only able to estimate the cost per year for a homeless person? How is it possible that the estimate is so wide? Clearly, the range of $41,679 and $104,201 is significant. Even if that may mean in some areas it is as low as 41.7K and in others as high as 104K, that too begs investigation and added insights, doesn’t it?

From the New York Times…

“America’s Cities Could House Everyone if They Chose To” proclaims the headline in a New York Times editorial board member Binyamin Appelbaum op-ed, dated May 15, 2020. “Homelessness in the United States is the most extreme manifestation of a broader housing crisis. Even in the fat years before the coronavirus plunged the economy into recession, millions of Americans struggled to pay the rent, particularly in prospering coastal cities,” said Appelbaum.

He noted that: “Tonight, more than half a million Americans will sleep in public places because they lack private spaces. They will huddle in crowded New York City shelters, or pitch tents under highways in Washington, D.C., or curl up in the doorways of San Francisco office towers, or dig holes in the high desert of northern Los Angeles County.

They are homeless, and their lives are falling apart. They struggle to stay healthy, to hold jobs, to preserve personal relationships, to maintain a sense of hope.”

The root cause that NY Times editorial writer proclaimed?

“They are victims of America’s wealth — and its indifference.”

His solution? Remove the deductions on home ownership, and apply that ‘savings’ to the costs needed to bear the ever-rising burdens of homeless programs. “The federal government could render homelessness rare, brief and nonrecurring. The cure for homelessness is housing, and, as it happens, the money is available: Congress could shift billions in annual federal subsidies from rich homeowners to people who don’t have homes.” It may be a classic case of confirmation bias: a problem is correctly identified. Several of the tragic facts are accurately, and even passionately, depicted. But then the supposed solution that is advanced misses the mark completely. Out of some 2100 words, “zoning” as a possible cause of this issue isn’t mentioned. More affordable housing in the form of “manufactured homes” is not mentioned by Appelbaum, who the NY Times then said was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize.

The Latest 2022 Facts and insights from CNBC

Note that several of these sources are from the left of center, such as The NY Times or CNBC. Fundamentally facts are not left or right, so long as they are accurate facts that reflect the evidence. That noted, “Why The U.S. Can’t Solve Homelessness” was the headline on CNBC on 1.7.2022. “The Covid pandemic caused a surge in housing costs and a rise in unemployment, leaving nearly 600,000 Americans unhoused in 2020. So how is the U.S. addressing the homelessness crisis and can the current housing first policy approach solve it?”

“Right now, we are trending in the wrong direction,” said Anthony Love, interim executive director at the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness. “The state of homelessness is pretty tenuous, and there are some small increases that are taking place across the board.”

For decades, the U.S. has relied on a “housing first” approach to homelessness, where permanent housing is provided for homeless people without preconditions such as sobriety or employment.

From the video above at about 8.32 time mark, the “Housing First” advocate says spending annual spending is 50K per person to sometimes 100K per year per person, ‘and the individual is still homeless.’

At about the 14 minute time mark, the statement is made that there is ‘nowhere near the investment needed to provide affordable housing.’

A member of the Manhattan Institute, Stephen Eide, says at about 14:29 that it is “very disgraceful” that our nation hasn’t solved the affordable housing crisis. Indeed, that is so.

“When the public is told that this particular policy is going to end homelessness, what they’re expecting is that they’re going to see fewer homeless people around,” said Eide, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute. “I don’t think that we’ve seen that in the case of housing first.”

Watch the video to find out more about the homelessness crisis in the U.S. and what the nation is doing to address the issue.

MHProNews Note: This video is like the one above but is provided to offer various devices the maximum opportunity to see this video report.

A Prior Reports Estimate…

“A chronically homeless person costs the taxpayer an average of $35,578 per year. This study shows how costs on average are reduced by 49.5% when they are placed in supportive housing. Supportive housing costs on average $12,800, making the net savings roughly $4,800 per year. So said EndHomelessness.org on 2.17, 2017.” That was almost 5 years ago. If that figure is applied to the estimated 2020 homeless count of some 580,000, the math then was a total annual cost of over 20 billion for spending tied to homeliness. Here’s the formula: $35,578 x 580,000 = $20,635,240,000.

Let’s boil down some of the takeaways from the vantagepoint of affordable housing advocacy that the above provides. Yes, homelessness may be complex and have a variety of symptoms and causes. But what the NY Times’ Appelbaum said, cited above, is apt. “Homelessness in the United States is the most extreme manifestation of a broader housing crisis.” Quite so. If people working on lower wages can afford housing, then common sense alone says that the odds that they will become homeless drops.

While there are numerous troubling, yet insightful, points made, none of them specifically cited the issues that MHProNews pointed out that HUD Researchers Pamela Blumenthal and Regina Gray made on 9.7.2021. Namely, that the causes and cures for the affordable housing crisis are known.

“Without significant new supply, cost burdens are likely to increase as current home prices reach all-time highs, with the median home sales price reaching nearly $375,000 by July 2021. These data emphasize the urgency of employing opportunities for increasing the supply of housing and preserving the existing housing portfolio.” So said Blumenthal and Gray.

They then pointed toward arguably part of the root cause.

“The regulatory environment — federal, state, and local — that contributes to the extensive mismatch between supply and need has worsened over time. Federally sponsored commissions, task forces, and councils under both Democratic and Republican administrations have examined the effects of land use regulations on affordable housing for more than 50 years. Numerous studies find land use regulations that limit the number of new units that can be built or impose significant costs on development through fees and long approval processes drive up housing costs. Research indicates higher housing costs also drive up program costs for federal assistance, reducing the funds available to serve additional households.”

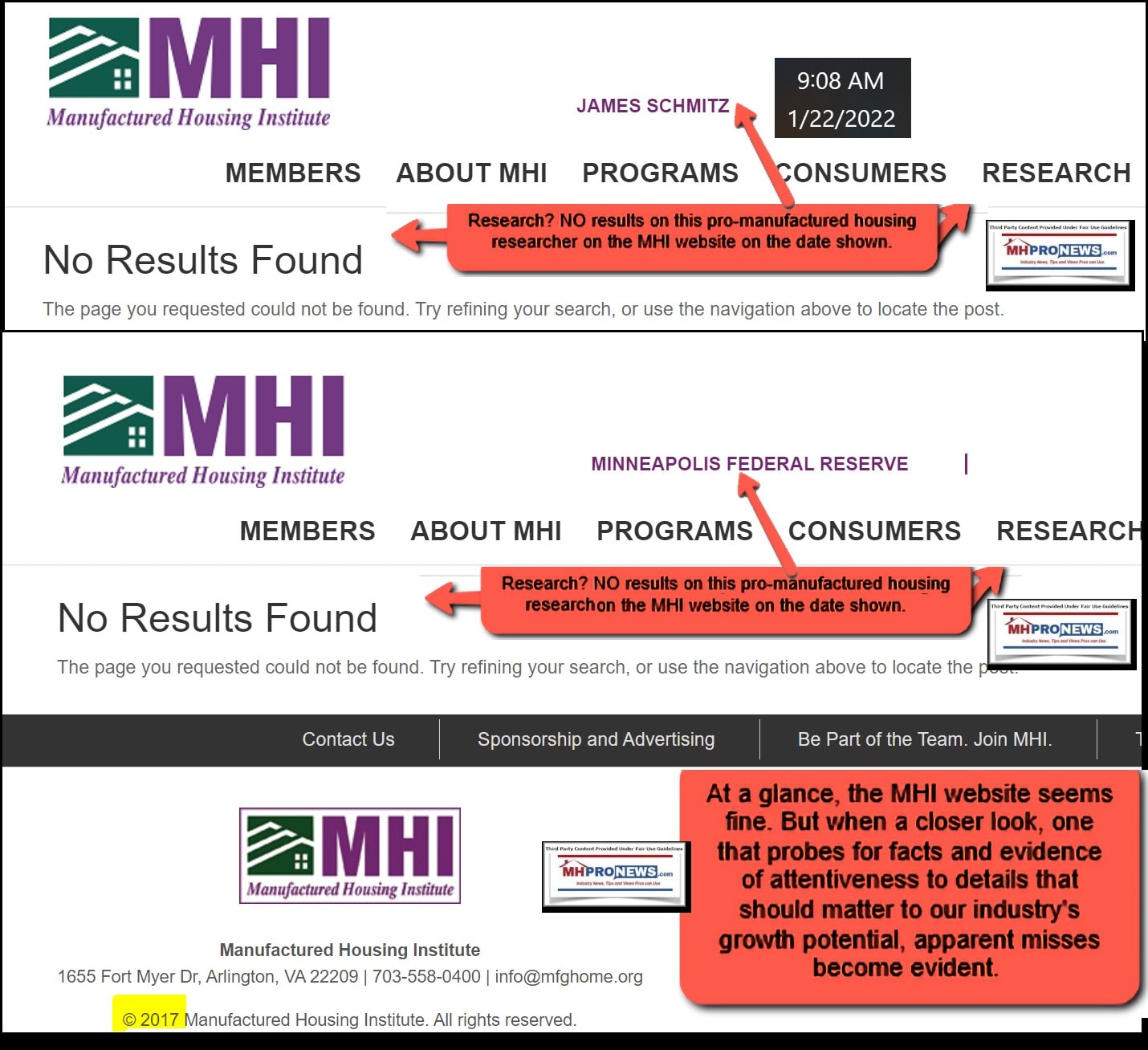

Why hasn’t this compelling point been repeatedly raised by the self-proclaimed leaders of production and post-production advocacy in manufactured housing, namely the Manufactured Housing Institute (MHI)? Hold that thought.

From the Minneapolis Federal Reserve and ProMarkets.

MHProNews won’t go into the details already previously published by Minneapolis Federal Reserve researchers such as James A. “Jim” Schmitz and his colleagues. In economic research reports published on the Minneapolis Fed website, as well as on ProMarkets, they have specifically mentioned manufactured housing as a key part of the solution to the underlying problems of homelessness. They pointed the finger at builder, nonprofit, and HUD failures.

From a different nonprofit, the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) Housing Center, Tobias Peter politely but bluntly told Congress last year that federal policies are causing the affordable housing crisis.

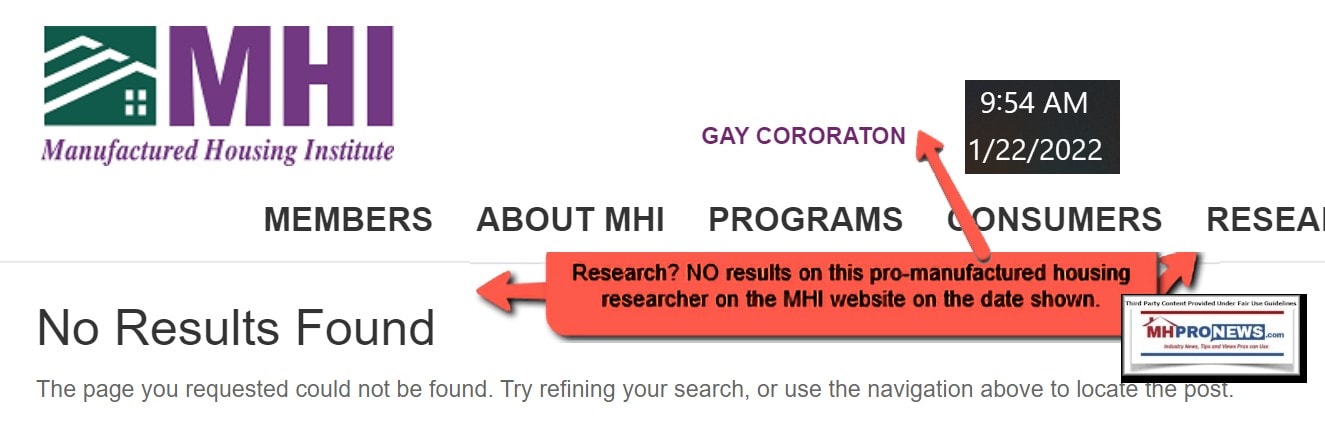

Again, why hasn’t MHI even mentioned their research work on their own website? Note these site-searches on today’s date that illustrate the lack of MHI engagement on the importance of these third-party researchers’ respective findings.

Among the current lower-side estimates of the cost per capita for costs and issues related to dealing with homelessness is about $50,000 per person. If the number of homeless stands at about 600,000 – and it may prove to be higher, based on the post-COVID19 related economic impacts – then some $30 billion dollars a year is being spent on the federal, state, and local levels.

Per the U.S. Census Bureau’s most recent data set are the following national facts on the cost of single section and multi-sectional manufactured homes.

| United States | |||

| Total1 | Single | Double | |

| 2021 | |||

| August | $112,000 | $80,000 | $138,000 |

| July | 118,700 | 76,000 | 137,800 |

| June | 106,800 | 70,200 | 128,100 |

| May | 106,500 | 69,900 | 128,300 |

| April | 100,200 | 66,700 | 122,500 |

| March | 98,100 | 63,300 | 123,200 |

| February | 98,300 | 65,400 | 122,500 |

| January | 95,000 | 64,100 | 118,500 |

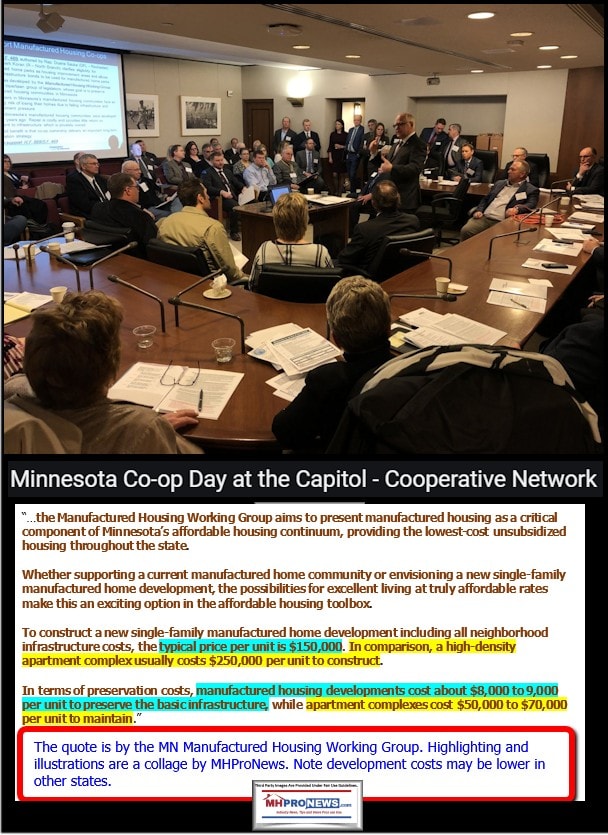

While the cost to develop a homesite ready for a manufactured home placement will vary by region and location, in many regions, $40,000 to $50,000 would be adequate.

Using $45K for home site, and 85K for roughly the current price of a single-section manufactured home, the total cost would be about 130K. At those figures, about 230,769 manufactured homes and sites could be completely paid for annually. In less than 3 years, that simplistic notion could mean that there would be no homelessness in America. That estimated $30 billion a year in taxpayer funded spending could then be saved.

Clearly, there is more to it than that outline. But that 3 years to end homelessness points toward the built-in shortsightedness of the various parties that are examining this issue. It also points to the apparent utter failure of MHI – which claims to represent “all segments” of manufactured housing as an effective or even cogent advocate.

It isn’t that MHProNews is advocating for government to pay for free housing for all the homeless. A free housing program would create its own issues. But it illustrates the point that the current patterns for decades are a bridge to nowhere. As Blumenthal and Gray said, as construction costs rise, the amount of money needed for these various public projects only rises with it. There is no end in sight, unless…

…the underlying issues are addressed. Congress did so with good legislation in 2000 and 2008, among other examples. The Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000 (MHIA) made overcoming those barriers that Blumenthal and Gray state are near the heart of the issues could be overcome. Why hasn’t MHI sued to get that enforced?

In terms of financing, there are an array of programs that could help the employed or retired on modest incomes to afford manufactured housing that better fits their budget and allows them to build equity. This has been demonstrated by Scholastica “Gay” Cororaton in research MHProNews/MHLivingNews has repeatedly cited. But approaching four years since the release of her seminal work that is largely pro-manufactured housing, her name is still not found on the MHI website.

MHLivingNews offered a similar solution to the above years ago. That was done while our parent company was an MHI member. Why hasn’t MHI ever picked up that theme and run with it?

Summing Up and MHProNews Fact and Evidence Based Additional Commentary

To wrap this segment of today’s report up, here are some bottom-line lessons learned.

- The causes and the cures to the affordable housing crisis and even to homelessness are broadly known.

- The system at this time ignores, for whatever reason, the underlying issues that have kept the status quo locked in a ditch that never ends.

- As the late Zig Ziglar used to say that a rut is an open-ended grave. It is time for a Ziglar-style checkup from the neck up.

A range of interest groups either want or get the benefit of pleading their respective cases for issues that have over the course of decades proven not to work. The time to pivot is sooner than later. The need for effective and common-sense advocacy on all governmental policies is now. On the post-production side, that advocacy clearly has not come from MHI. The most obvious proof of that is the production levels. Manufactured housing is operating at only about 30 percent of its last highwater mark. A modest estimate of what manufactured housing is capable of doing came from prior MHI president and CEO, Richard “Dick” Jennison. He said the goal should be 500,000 homes a year. Then why is the industry only now crossing the 100,000 threshold for the first time in over a dozen years?!

MHI’s failures are thus logically harming millions of citizens and thousands. A new post-production trade group needs to be forged. One that will work with the Manufactured Housing Association for Regulatory Reform (MHARR), which has successfully advocated on the production side of issues for decades.

The time has also come that public officials and/or private attorneys investigate and perhaps take legal action as warranted against those corporate and staff leaders at MHI who have allowed this disgraceful pattern to exist for so long.

Solving homelessness is tied to solving the affordable housing crisis. Manufactured homes are the most proven form of affordable housing in U.S. history. Let’s put common sense to work in an honorable and profitable fashion.

Let’s move onto the rest of the macro and industry-specific equities and market reports.

https://www.manufacturedhomepronews.com/business-and-sales-meeting-2022-affordable-housing-and-manufactured-housing-reality-checks-shadows-reflections-inspirations-musings-from-industry-news-tips-and-views-pros-can/