Mark Dillard, Executive Director at the Manufactured Housing Institute of South Carolina (MHISC) uses a photo of a vacant lot near his office, just blocks from the state Capitol to demonstrate the potential to place manufactured homes on vacant lots throughout the state. In the state capital of Columbia, Dillard says there’s already a trend of bringing condos and retail downtown, and the addition of more moderately priced workforce housing in the form of manufactured homes makes sense.

Mark Dillard, Executive Director at the Manufactured Housing Institute of South Carolina (MHISC) uses a photo of a vacant lot near his office, just blocks from the state Capitol to demonstrate the potential to place manufactured homes on vacant lots throughout the state. In the state capital of Columbia, Dillard says there’s already a trend of bringing condos and retail downtown, and the addition of more moderately priced workforce housing in the form of manufactured homes makes sense.

Single-section HUD-Code Home, Oakland, California

Most manufactured homes produced today are destined for suburban and rural locations, and Dillard’s vision would defer to the exception rather than the rule. Experts say an increasing amount of residential development in the coming years will be in urban areas and inner suburbs. Even within the suburbs, development will not be of the ranch-style-home-on-half-acre-lot most manufactured homes emulate, but of the new urban sort with sidewalks and a mix of retail office and residence. It’s a cost-effective thing for the utilities and municipalities, says Dillard. “What we’ve seen thus far is condos, but we’re talking about individual affordable homes. It seems like it fits the trend.”

Even so, this may present a problem as well as an opportunity for the manufactured housing industry.

An article in the Journal of the American Planning Association (JAPA) earlier this year argues that manufactured housing could solve the affordable homes crisis in urban areas, but only if planners help local people to overcome their prejudices.

Writing in the winter issue of JAPA, two leading urban affairs and planning experts—Professor Casey Dawkins and Professor Theodore Koebel from the Center of Housing Research at Virginia Tech—urge urban planning officers to support proposals for manufactured homes. The research was sponsored by HUD and has yet to be released in its entirety.

In the research, Dawkins and Koebel argue that the planning process discriminates against people with low incomes unless planners speak up for the design improvements, longevity, and value for money that make manufactured housing a feasible and affordable alternative to traditionally built homes.

Their new research shows that planners see high land prices and citizen opposition as the biggest barriers to manufactured housing developments in urban areas.

According to the journal article, government subsidies—including grant and loan programs supporting low-cost housing construction and rehabilitation, tax incentives and gap-financing programs for low income borrowers, tax credits for affordable housing production, and public and nonprofit ownership—have been the most common tools for increasing the supply of affordable housing in the United States. Alternatively, policy could focus on reducing market barriers to low-cost housing producers.

In South Carolina, Dillard says a major barrier is zoning restrictions.

“A lot of the municipalities in South Carolina banned manufactured housing 20 or 30 years ago,” Dillard explains. “We’re looking for opportunities to talk to them about affordable housing and the declining population a lot of municipalities have.” It’s that window for conversation, opened by the sagging economy that may help bring changes to zoning laws to welcome manufactured housing.

The potential application for manufactured housing in this arena is significant. Absent subsidies, the researchers at Virginia Tech say manufactured housing costs less per unit than any other housing type because of economies of scale in production and because it uses standardized inputs and labor processes. In metropolitan areas with high land costs, manufactured housing offers potential for substantial cost savings by substituting other inputs for land.

Koebel told MHMSM.com that high land costs in urban areas make residential development with a low price point problematic. That has been helped with the use of modular housing, and it can also be addressed with manufactured housing, but builders are not likely to mix the two.

“Most builders are not going to do mixed-production types in a subdivision,” Koebel says. “It’s a question of how are you going to do subdivisions that are going to pay for the cost of land. It’s hard to do it with any type of construction with a modest price point. If they’re going for a modest price point, they’re either going to go modular or manufactured, I don’t think they’re going to be mixing and matching.”

If the zoning laws can be amended to allow manufactured housing, Dillard says there are benefits for South Carolina’s cities and towns. The first is a reduction in suburban sprawl, which he says is a frequent goal in the state. The second is a savings on infrastructure costs. Another prong of their approach has been to contact power companies and explain the benefits of using manufactured housing for infill development. He points out that a power line with 10 houses on it is more efficient than one serving six. Municipalities can realize those same benefits with transportation and sewer and water infrastructure.

Previous Efforts at Infill and Brownfield Development

There have been efforts and successes over the years to bring manufactured housing to both brownfield and infill sites in urban areas. Most notable perhaps is Oakland, California.

“Oakland is certainly an example of using HUD code to promote infill,” Koebel says.

Structural innovations now allow modestly pitched roofs, as well as two-story stacking of units, although most manufactured housing units do not have these attributes. Those innovations have helped the East Bay city to demonstrate the utility and cost advantages of placing manufactured housing on infill lots in a built-out city.

Multi-section Single-family HUD-Code Home, Oakland, California

There are other examples including several in the Pacific Northwest the researchers looked at. Also in 1997 the Manufactured Housing Institute (MHI) undertook a pilot project to bring manufactured homes to five major urban areas. Working in conjunction with architectural firm Susan Maxman & Partners, the project focused on Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania; Washington, D.C.; Louisville, Kentucky; Birmingham, Alabama; and Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Later in a 2003 showcase example, the Mills of Carthage project in Cincinnati brought 15 manufactured and modular homes to a brownfield site there.

MHI says on its web site the initiatives were intended to address the outdated assumption that manufactured homes are not appropriate for placement in major urban and suburban areas. Also in the case of the 1997 initiative, the project was designed to highlight any impediments and challenges to using manufactured homes, and help pave the way for a more extensive use of manufactured housing in future efforts.

The North Carolina Manufactured Housing Institute (NCMHI) began another venture to demonstrate that manufactured homes can be architecturally compatible with existing homes in urban settings and also be a solution to the affordable housing crisis facing many of the state’s urban and inner suburban areas.

The result was an attractive three bedroom, two bath, 1500-square-foot home in the shadows of the North Carolina statehouse in downtown Raleigh. Designed complete with a factory-constructed front porch, the house blends in with the 1920s bungalow-style architecture of the neighborhood in the southwestern part of the city. It was also priced some $80,000 less than comparable homes in the neighborhood.

The result was an attractive three bedroom, two bath, 1500-square-foot home in the shadows of the North Carolina statehouse in downtown Raleigh. Designed complete with a factory-constructed front porch, the house blends in with the 1920s bungalow-style architecture of the neighborhood in the southwestern part of the city. It was also priced some $80,000 less than comparable homes in the neighborhood.

Yet despite its affordability and quality, manufactured housing continues to face opposition and legal barriers. In Raleigh the new home was allowed under an exception to a Raleigh city ordinance, which currently prohibits manufactured housing within the city.

Those issues are not confined to North Carolina. As the Virginia Tech researchers point out, perhaps the most significant barrier to siting new manufactured homes in metropolitan areas is the presence of zoning codes that restrict the size, design, location and even existence of manufactured units.

Overcoming Barriers

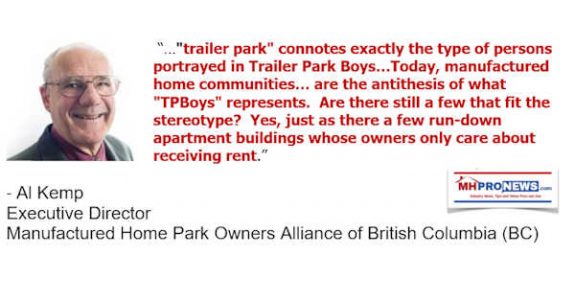

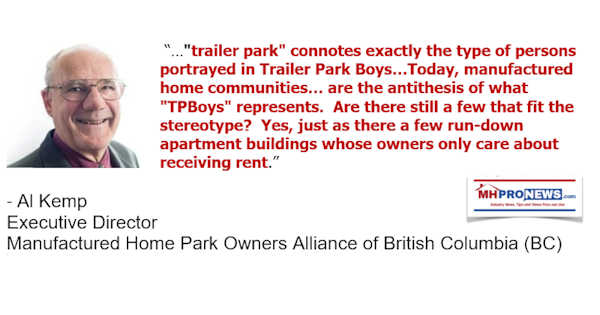

According to the research, several factors motivate local governments to adopt these and other manufactured housing regulatory barriers, including general prejudice against all forms of low-cost housing and the low aesthetic appeal of the traditional but outdated “trailer park” community design. Citing a variety of research, the authors conclude that planners are also influenced by erroneous perceptions that manufactured home residents constitute a transient population, that manufactured housing is substandard and unsafe, and that manufactured housing appreciates more slowly than traditional site-built homes and negatively influences adjacent housing prices.

However, as the authors point out, evidence suggests that nearly all of these claims are either illegitimate or unwarranted. Despite this evidence, negative stereotypes of manufactured housing persist, making it likely that local government officials will continue to impose regulatory restrictions on such housing.

A 1996 survey of 1,172 communities conducted by the American Planning Association, found that while almost all communities permit manufactured homes in some residential districts, on individual lots, considerably fewer allow them in all or in the most restrictive residential districts. Only 29 percent of responding communities had regulations that treated site-built homes and manufactured homes comparably.

“Our research shows that having a HUD code subdivision increases the number of homes going into an area,” Koebel says. “Having more land already zoned—small lot development at modest price points—and having areas of that sort identified and pre-zoned helps increase the number of units.”

Tri-section HUD-Code Home Located in the Hills, Oakland, California

The authors received responses from 940 communities regarding the perceived barriers to placing manufactured housing. The survey respondents were asked to rate a list of potential barriers to HUD-code homes. The potential barriers with the largest share of respondents saying they were significant or would prevent placements were: the high cost of land (42.4 percent), citizen opposition (36.1 percent), no new parks (35.6 percent), zoning codes (33.4 percent), not much land (31.1 percent), deed restrictions (26.8 percent), and historic district regulations (26.1 percent). Fees, permits, wind codes, snow load standards, fire codes, and environmental regulations were the most likely items to be identified as “not a barrier” or a “minor barrier.”

The authors also found that by-right zoning, when manufactured housing is treated equally in single-family housing districts, has a positive impact on unit placement that is greatest when explaining whether a community has any manufactured housing placements at all as opposed to none. The effect of by-right zoning on the odds of placing one unit or more is three times higher than it is on the odds of placing more than 20 units. Above 50 units, the impact of by-right allowances diminishes in magnitude even further, although it is still statistically significant.

To some in the industry the idea that local zoning can impact the placement of manufactured homes in urban areas, or anywhere, runs counter to the intent of the Manufactured Housing Act of 2000 that says the HUD code should be broadly and liberally interpreted. Local zoning or aesthetic requirements, as well as building requirements, cannot be placed on homes built to the HUD code.

But Koebel says most manufactured housing placement has come by way of state preemption that allows manufactured homes in single-family neighborhoods.

“I think HUD and the federal government would be highly reluctant to get into the details of preemption in terms of land-use regulations,” Koebel comments. “That’s just such a heavily state-oriented function. Some states require that you allow manufactured homes in single-family zones as a by-right use. You usually have that with some design standards. I personally don’t think the federal government is going to take on state and local governments on that.”

HUD Program Manager Edwin Stromberg told MHMSM.com the research was part of a wider effort to gain insight into barriers to affordable housing and that the report should be released within the next few months.

How Big is the Potential Market?

According to a 2009 study by RCLCO, both retiring baby boomers and maturing echo boomers are looking to move away from the suburbs. Both groups reported wanting to live in more urban, mixed use, mixed age areas that offer services, community and walk-ability. A study released in 2009 by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency titled “Residential Construction Trends in America’s Metropolitan Regions” shows that there has been a striking move back to the urban core in many markets. While Generation X is small, experts say the larger Generation Y will be looking for urban amenities, but may not be able to afford living downtown.

Manufactured Housing Institute Executive Vice President Thayer Long says Generation Y, the next generation of homebuyers, is a group bigger than the baby boomers and just coming of house purchasing age. The group is more environmentally aware and as far as preferring urban areas, Long says there may be more opportunities for the manufactured housing industry to get involved.

Most manufactured homes produced today, and at any time in the past, however, are destined for rural and suburban areas. For the past half-century the bulk of new residential development has occurred in greenfields, which is land that hasn’t been previously built on. Researchers now say the amount of new development occurring in brownfields and urban infill is on the rise. Manufactured home producers may wonder what the risk is of not meeting the needs of the urban market or homebuyers who prefer walkable urban districts.

“If we reached the point of having 25 percent infill/brownfield, that would be achieving a great deal,” Koebel says. “There’s some evidence that infill and redevelopment has increased market share.”

Koebel says modular products are well suited to infill development and that there are systemic barriers to significant placement of manufactured housing in high-priced urban areas.

“The industry got itself into a market segment that’s targeted to a rural, lower-end product and has never figured out how to take advantage of other market segments,” Koebel says. “Partly it’s the retail structure. The industry has serious problems with path-dependency. It got itself into a rut in terms of how you use the product and who is the market for the product, all the way down to how it gets advertised and sold; all of that becomes reinforcing and limits its use in urban areas.”

Conclusions

The researchers conclude planners can promote affordable housing by projecting the potential demand for manufactured housing in a number of ways including devising educational programs to promote community acceptance, reviewing and modifying existing regulations so they treat manufactured housing the same as site-built single-family housing and by designing incentives to promote affordable redevelopment using manufactured housing on vacant infill lots.

Dawkins and Koebel want planners to educate their local communities away from thinking that manufactured housing means “mobile” homes, “trailer parks,” and anti-social behavior.

For Dillard, the solution is about education, but also about promotion. Part of his vision is to have major producers set up a cul-de-sac showcase of manufactured homes where they can be on display and later purchased.

But that’s down the road. For now, with the photo of a vacant lot in hand, he’s working to win over municipalities one at a time.

Notes:

HUD photos: Thanks to Steve Hullibarger

(Raleigh Photo: http://www.manufacturedhousing.org/developer_resources/urban_design_raleigh.asp

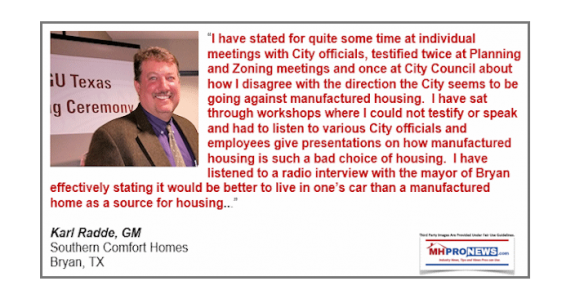

Karl Radde – TMHA, MHI, Southern Comfort Homes – Addressing Bryan City Leaders, Letter on Proposed Manufactured Home Ban

To All Concerned [Bryan City Officials, Others]: As the retail location referenced by Mr. Inderman, I would like to take a moment to address the …