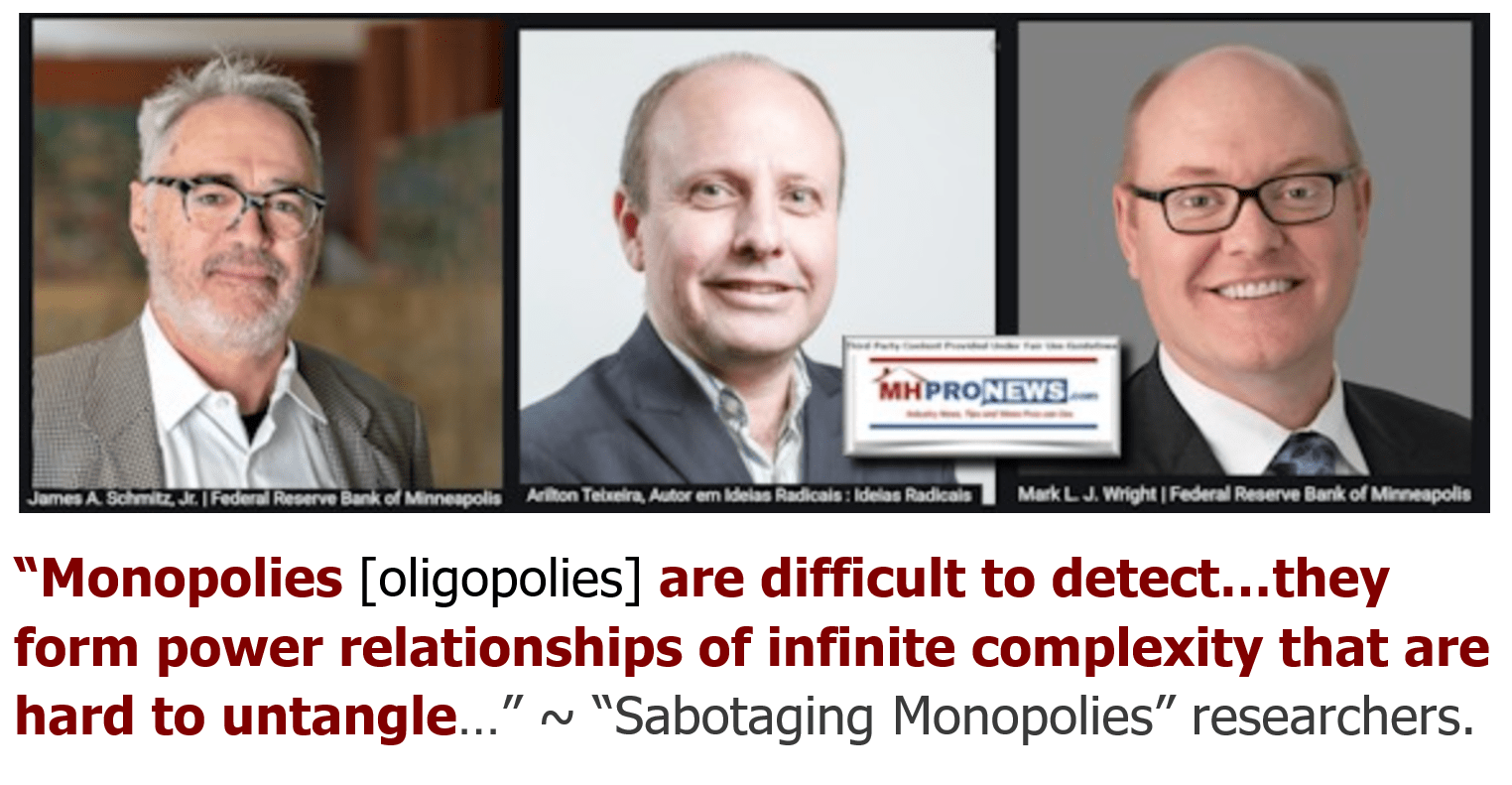

Berkshire Hathaway (BRK). BlackRock (BLK). Vanguard (several stock symbols). State Street (several stock symbols). Those companies are financial giants. They are among the deepest corporate pockets on planet Earth. Those four mega-corporations are all invested in various aspects of HUD Code manufactured housing. Which should beg the question. Why is this uniquely U.S. industry underperforming so during a well-known affordable housing crisis? Why is manufactured housing looked down upon despite numerous studies that show their value, resilience, and affordability? Rhetorically, firms with collectively trillions of dollars in assets under management should be able to accomplish proper lobbying, education, advocacy and research promotion, right? Speaking of research, the “Mass Production of Houses in Factories in the United States: The First and Only “Experiment” Was a Tremendous Success*” provided in Part I of this report with analysis are the views of Dr. Elena Falcettoni, James A. Schmitz Jr., and Mark L. J. Wright. Dr. Elena Falcettoni, Ph.D., is the Senior Economist at Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, per her LinkedIn page. According to their website, Jim Schmitz joined “the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis in 1992. He is currently a senior research economist at the Bank and a visiting professor in economics at the University of Minnesota.” Mark Wright is the Senior Vice President at Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, per his bio-in-brief at their Fed branch website. That trio have brought attention to the promise and plight of HUD Code manufactured housing. Shining an evidence-based and rational spotlight on manufactured housing and its mobile home predecessor are potential pluses for the industry. That those three, who along with their collogues who produced previous research on the subject of manufactured housing and the effects of ‘sabotage monopoly’ tactics in limiting the industry, have curiously been routinely ignored or downplayed by the Manufactured Housing Institute (MHI) and/or their allied bloggers and trade publishers is a matter previously documented in reports like the one linked here.

So, much of what Falcettoni, Schmitz, and Wright have published is potentially useful for those who are sincerely eager to solve the affordable housing crisis in the U.S. That said, an authentic analysis must disclose that some of their terminology and data could and should be refined and addressed. The views expressed in Part I of this report are theirs, while the views in this preface, Part II and Part III are those of MHProNews.

Berkshire Hathaway, BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street are not mentioned by in this research by Falcettoni, Schmitz, and Wright. Their research is useful, but not exhaustive. It will be MHProNews that brings in Part II of this research some arguably related insights that can round out their important findings.

Professor Schmitz thoughtfully provided MHProNews with a copy of their latest entitled: “Mass Production of Houses in Factories in the United States: The First and Only “Experiment” Was a Tremendous Success*” The abstract and the first section of their research are found below. A more detailed look on their research is planned in the days ahead on our MHLivingNews sister site.

Speaking of Buffett led-Berkshire, keep in mind that no longer young man has said that reading is one of his most important and valuable habits. Buffett reportedly reads 5 to 6 hours daily. What’s provided is not a quick read, it can be read in a small fraction of Buffett-style reading time. Grab your favorite beverage. If you need a snack, get that while you are at it.

Some additional observations will follow the research by Falcettoni, Schmitz, and Wright which their entire research document as provided is found at this link here. Brackets in Part I below are added by MHProNews to clarify meaning and/or for accuracy’s sake. Some spacing errors and hyphenation were added by MHProNews, which in fairness may have been the result of conversions back and forth from WORD into PDF. It will be later in Part II that the relationship of Berkshire Hathaway, BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street will be introduced by this writer for MHProNews as part of our analysis and commentary.

Part I

Mass Production of Houses in Factories in the United States: The First and Only “Experiment” Was a Tremendous Success*

Abstract

We show that the first and only experiment of U.S. mass production of houses, in a factory-built home industry that became known as the Mobile Home industry (and today, as the Manufactured Home industry), was a tremendous success. Mobile Home prices–psf [i.e.: per square foot] fell by two-thirds from 1955 to 1973, as productivity soared; home quality rose significantly, with Mobile Home building codes receiving ANSI certification in 1963 and National Fire Protection Association co-sponsorship in 1965; as production soared, Mobile Homes accounted for one-third of single-family homes produced in the early 1970s. These feats were achieved as industry leaders developed state-wide building codes for Mobile Homes. This dramatically increased the size of the market for them. Factories invested in specialized machinery to produce simple and standardized products, substituting machinery for labor. Given each factory produced under the same code, industry-induced productivity gains followed, including external effects and directed technical change. Lessons from this industry give insights into critical issues in today’s residential construction industry. The poor productivity performance of today’s residential construction industry is considered a puzzle. But this poor performance is not new. Our forebears before 1950 wrote extensively about the sector’s poor performance, attributing it to the failure to adopt factory-built housing. Our analysis strongly supports this view – for their time and ours. It also supports their view, like that of Levitt & Sons, that factory production is the only way “to produce the homes and apartments needed to house our expanding population and our underprivileged citizens in a comfortable, dignified, decent way,” (U.S. Senate 1969).

1 Introduction

Mass production in factories ushered in dramatic price declines in a wide range of goods – automobiles, bicycles, clothing and more. It did so by developing simple versions (“no bells and whistles”) and standardized versions (products with uniform features) of craft-produced goods, and by using highly specialized machinery and a standardized manufacturing process. Mass production greatly expanded consumption opportunities for low- and middle-income families.

Housing was an obvious candidate for mass production, as it accounted for large shares of low- and middle-income household budgets. Moreover, the construction methods used by craft producers during the first half of the 20th century, sometimes called “stick-built” methods, were hundreds of years old.1 However, housing has always faced a somewhat unique problem when trying to achieve mass production. When Henry Ford produced cars in one of his factories, there were no local producers of cars in that area. When a producer manufactured a home in a factory, there were always local craft-builders of homes in the area – and typically they fiercely resisted the factory-built homes.

So, while many groups attempted to mass produce housing during first half of 20th century, hoping to accomplish for housing what had been achieved for other goods, they faced significant opposition from stick-builders. None of the attempts at mass production succeeded.2

It was not until the late 1940s that a successful effort was launched in a new sector of the factory-built-home industry, which came to be known as the Mobile Home industry (now called the Manufactured Home industry).3 The experiment was brief, lasting from roughly 1948 to 1973, yet it achieved what had been hoped for — factory-built homes greatly expanded home ownership for low and middle income households. From 1960 to the early 1970s, Mobile Home industry production rose from 100,000 to [approaching] 600,000 units a year, and it was rising as fast as ever. Its share of single-family housing production was one-third in the early 1970s, and rising; it exceeded 50 percent in 14 states.4 Not only was this episode the first successful U.S. experiment in mass producing homes, it remains the only one.

The purpose of the paper is to seek to understand how the Mobile Home industry achieved mass production. We argue it was the industry’s ability to develop state-wide building codes that led to its success.5 Factory-built homes that predated Mobile Homes, homes that we discuss throughout the paper and break into two groups, “Modular Homes” and “panelized homes,” were built to local building codes.6 A home manufactured for one town’s code could be sold there, but not in other nearby towns with different codes. A major consequence of state-wide building codes for Mobile Homes was to increase the size of the market for them relative to other factory-built homes. With a state-wide code — that is, an identical building code for all locations within a state — a home manufactured for a given town could be sold at any location in the state.

This expansion of the market for Mobile Homes led to many sources of productivity gains, which we divide into factory-induced gains and industry-induced gains. It created incentives for a “factory” to invest in specialized machinery (and layout designs) to produce simple and standardized products.7 These investments led to factory-induced productivity gains, as the factory increased its scale, and simultaneously replaced high skill workers with machinery and low skill workers.

While productivity gains followed from a factory producing under the same code (or process) for each of its houses, other productivity gains followed from each factory in the industry producing under the same code. These industry-induced gains included external effects (or spillovers) and directed technical change (i.e., the innovation of suppliers).8

There was another key factor that enabled the industry to achieve mass production.9 As we said, factory-built homes have always been resisted, including those that predated Mobile Homes. But the opposition to Mobile Homes was far greater. Opponents in the stick-built industry successfully argued that Mobile Homes weren’t homes at all. Mobile homes were consequently banned from traditional residential areas. Mobile Home manufacturers were forced to develop markets in areas where there was little local control over Mobile Homes. The mass production “experiment,” then, consisted of an identical state-wide code, coupled with little local control over the homes.

While the mass production of Mobile Homes is the main focus of the paper, we’ve learned important lessons about other critical issues. Here are some questions we discuss: (1) Why did mass production of Mobile Homes end in 1973?; (2) Why haven’t other factory-built home industries achieved mass production?; and (3) Why has the residential construction industry had such a poor productivity performance over the last several decades?

Our initial research on the Mobile Home industry was, in fact, directed at understanding why the industry collapsed after 1973. The research shows, in short, that the industry was sabotaged by those opposed to its success – groups of stick-builders, of course, but many others, like particular groups in the financial industry that financed Mobile Homes as cars (see Schmitz, Teixeira and Wright (2018), Schmitz (2020a) and Schmitz (2020b)).

Further research over the last few years has found more evidence that the collapse was due to such sabotage. We briefly discuss this research below. This research will be compiled in a companion paper. We decided to first explore the period of mass production, in this paper, before completing the companion paper.

In this introduction, we begin by describing the banning of Mobile Homes from traditional housing channels. This banning, paradoxically, set the spark that led leaders of the Mobile Home industry to develop state-wide codes.10

Banning of Mobile Homes. Factory-homes that pre-dated Mobile Homes, again, Modular Homes and panelized homes, were not banned from traditional housing channels. They were permitted in single-family residential districts. They were subject to the same building codes and zoning ordinances as traditionally built homes. But they faced significant opposition. Many methods were used to block them, but that these factory-homes were subject to the same “local” building codes as stick-built homes essentially shut off any chances of mass production. These “local” building codes typically varied widely from town to town. A home manufactured for a given town could be sold in that town but not elsewhere. To sell to another town, with its own building code, would require a different manufacturing procedure, meaning the specialized machines would need to be adjusted. This, of course, defeats the whole purpose of factory production, which is tied to repetitive production, thus reducing the incentive to invest in specialized machinery. When these factory-built homes were being introduced, local builders obviously strongly supported the continuation of local codes (and opposed any attempt to develop more uniform codes).11

It’s hard to imagine that the prospects of Mobile Homes were better than Modular Homes or panelized homes.12 Many opponents of Mobile Homes wanted to ban them outright. To ban Mobile Homes, opponents argued they were not homes at all – that they were “Trailers,” by which they meant the primitive forms of shelter that families had towed behind their cars searching for work during the Great Depression.13 To create this fiction that Mobile Homes were Trailers, opponents argued that both were placed on a chassis fitted with axles and wheels.14 For many local zoning boards, many of whose members were stick-builders or similar, this was enough to establish the fiction. Of course, the axles and wheels were never removed from the chassis of a Trailer — they were moved daily. After the delivery of a Mobile Home, the axel and wheels were always removed from the chassis. At the beginning of the industry, the chassis would often remain attached to the home. But as the industry developed, the chassis was removed, and the house often placed on a permanent foundation.

Mobile Homes, then, were banned from residential areas.15 Yet the industry developed markets in two types of areas where there was little local control over Mobile Homes. First, while many towns banned Mobile Homes entirely (i.e. from residential areas and all other areas), other towns permitted Mobile Homes in industrial areas and dumps, but then typically restricted them to Mobile Home parks.16 When Mobile Homes were placed in these industrial areas, there were no local building codes for houses. Second, Mobile Homes were placed in towns that did not engage in “building regulation activities.”17 As reported in United States Congress (1969a, Table 2, p. 209) (the Paul Douglas report), of all towns in the United States, 46.7 percent had no zoning ordinances and 53.6 percent had no local building codes (see Manvel 1968).

Development of State-wide Building Codes. The leaders of the industry who formed a trade association, the Mobile Home Manufacturers Association (MHMA), recognized that if they developed a building code and they convinced states to make the code mandatory for all Mobile Home producers, then the industry would have an identical code at each location (where they were permitted) in the state. The MHMA accomplished this feat. The MHMA began developing codes in the early 1950s; by 1960, it had developed a code that it required members to follow. By 1963, the code was certified by the American Standards Association (later called ANSI, see below). In 1965, the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) joined as a cosponsor of the code. In 1965, the MHMA began lobbying each state to make the code mandatory for all manufacturers — not just MHMA members. By 1973, 44 states had done so (see Cooke, et al, 1974).

Industry-Induced Productivity Gains. As we argued, these identical building codes enabled the industry to achieve many sources of productivity gains. Here, briefly consider industry-induced gains. Again, with many factories producing houses built to the same code and using a similar process, manufacturers benefited from external effects. An important source of these spillovers was the development of organizations that built industry infrastructure. This infrastructure was useful to existing firms (and firms considering entry) and it was free of charge. The MHMA was obviously one such organization, as it developed the state-wide building codes that were necessary if the industry had a chance to mass produce homes. It developed many other types of infrastructure, as described below.18

Also, as the number of factories using a similar production process increased, the gains to suppliers of the industry in developing innovations grew as well. That is, the industry benefited from directed technical change. The MHMA recognized this. In the MHMA’s 1965 Annual Report, they wrote that “ … because of a concentrated, ready market, suppliers have been able to devote their research facilities to development of new products and applications which would not have been otherwise feasible.” The MHMA not only recognized this, but was actively engaged in supporting directed technical change as described below.

Great Success of Mass Production. Mobile Home prices-per-square-foot (prices-psf) were, initially, significantly higher than traditional home prices. This seemingly incongruous state of affairs highlights a great advantage of all factory-built homes — they can economically be made at small sizes.19 In 1955, the price of a Mobile Home was $18 per square foot (in 1960 dollars), compared with $11 for a stick-build home. In 1955, most Mobile Homes were 320 square feet, with a total cost of $5,760. Stick-built homes were on average roughly 1,100 square feet, with a total cost of $12,100. At $5,760, a Mobile Home was an option for low- and middle-income households.20

As gains from mass production accumulated over 1955 to 1973, Mobile Home prices-psf fell from $18 to $6. Over the same period, prices-psf for traditional stick homes (again in 1960 dollars) increased from roughly $11 to $12. Mobile Home prices-psf were half traditional prices-psf by 1973, and this relative price was falling fast.21

In addition, over 1955-73, the quality of Mobile Homes was significantly increasing relative to traditional homes. First, as we mentioned, when Mobile Homes were delivered to their housing site, it became common practice to remove their chassis and place them on a permanent foundation, often with a basement, just as traditional homes were. Second, the average size of Mobile Homes was increasing much faster than those of traditionally built homes. And third, the development of the state-wide Mobile Home codes meant that the standards of these homes were increasing much faster than traditional houses.22

Given significantly falling prices-psf and rapidly increasing quality, Mobile Home production soared. From 1960 to early 1970s, production increased from 100,000 to [approaching] 600,000 units, and was taking a larger and larger share of the single-family market from traditional builders. Not surprisingly, Mobile Homes were capturing the “lower-priced” end of the stick-built market, and were working their “way up” the price-ladder (see below).

Related Literature.23 Our forebears wrote extensively about factory-built housing and its great potential during the first half of the 20th century (see below). But after 1950, our profession simply forgot about factory-built homes and their great potential. One exception were the economists at Morgan Guaranty Trust Company (MGTC) who wrote a series of articles on the potential of factory-built housing in the late 1960s and the early 1970s.24 MGTC (1969) illustrated, for example, that over the period 1948-1968, residential construction costs rose roughly 100 percent, while prices of durable goods manufacturing (containing industries of similar nature to factory-built housing) rose only 22 percent.

Another exception were the economists writing about the Mobile Home industry during its era of mass production. Newman (1966) argued that Mobile Homes should play a significant role in U.S. housing production. Drury (1972) understood how the Mobile Home industry had been shunned from traditional housing channels yet was providing opportunities for low-income households. Greenwald (1970) wrote about the success of the industry but emphasized how much more could be achieved if not for the resistance to the houses. And MGTC (1971) discussed how the factory-built housing industry was already achieving great success with the Mobile Home industry.25

As our profession has written next to nothing on factory-built housing, there is obviously very little on building codes for such houses. There is a literature, though small, on local building codes. Here the emphasis is on the extent to which building codes are “excessive,” that they add unnecessary costs to building homes (see, e.g., Oster and Quigley (1977)).

A natural question here is: What would be the impact on the productivity of stick-built construction if local codes did not vary much over wide areas or, similarly, What would be the impact on their productivity if stick-builders could reach significant scale. There were such experiments in the 1940s and 1950s, such as that by Levitt and Sons on Long Island. As we argue in Section 6, these experiments were not mass production, as defined here, and as the Levitts acknowledged (see below, shortly), the methods did not solve the problem of meeting low-cost housing needs, as only factory-built housing could.

Other disciplines have written about building codes. A widely cited report published by the U.S. Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations (1966) (which we label ACIR) discussed building codes for factory-built homes. They emphasized the role of uniform building codes in the Mobile Home industry’s success. They pointed to its success to illustrate what uniform codes could accomplish in other factory-built home sectors.26

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 presents evidence on the zoning restrictions placed on Mobile Homes. Section 3 discusses how the Mobile Home industry developed state-wide building codes. Sections 4 (discussing prices and productivity) and Section 5 (discussing production) present the great success of the mass production of Mobile Homes. Section 6 argues the identical building codes led to many different sources of productivity gains, which set the stage for mass production. Section 7 shows the mass production experiment could have been much more successful if not for the great obstacles placed in the way of the industry.

Sections 8-10 address some of the questions listed above, with Section 8 discussing “Why date the end of mass production, really, the beginning of the end, in 1973?” The initial opposition to the Mobile Home industry involved local regulations, like zoning ordinances. As those regulations were failing to stop the industry’s growth, stick built producers turned to the federal level for ways to sabotage the Mobile Home industry. Several major federal initiatives were undertaken against Mobile Homes in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The crushing blow was HUD-sponsored 1974-legislation that marked the beginning of the end for mass production of Mobile Homes – that is why we date mass production from 1948- 1973.27 This legislation established a national building code (i.e., the “HUD-code”) for Mobile Homes that preempted the state-wide Mobile Home codes. The new code raised the costs of manufacturing the home while at the same time reducing its quality.28

— footnotes —

* The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, or the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. …

1For example, A.C. Shire (1937), who was the chief engineer of the Federal Housing Administration, wrote, “In an age of large-scale financing, power, and mass production, we have the anachronism that the oldest and one of the largest of our industries, concerned with the production of one of the three essentials of life … follows practices developed in the days of handwork … [and] is unable to benefit by advancing productive techniques in other fields.” He continued: “Unlike other widely used commodities, shelter is not made in a factory or plant organized for its production [our emphasis].”

2 See, for example, Thurman Arnold (1947) for how resistance by incumbents in the stick-built sector sabotaged factory production of homes. Arnold, among many other accomplishments, ran the antitrust division at the Department of Justice under FDR from 1938-1943. He brought indictments against many groups that were sabotaging factory-built homes during his tenure. More below on the sabotage of factory- built homes.

3 We have chosen to capitalize some words to avoid confusion. For example, the term “mobile home” is a generic term. As an Idaho judge explained, all factory homes “are, of course, necessarily mobile until they arrive at their destination.” (See judge’s remarks below.) So, we use “Mobile Home” for the type of factory-built home that is the focus of this study. The term “manufactured home” is also a generic term, one that refers to a home made in a factory. So, we use “Manufactured Home” to refer to the name given to Mobile Homes in the early 1980s.

[MHProNews Notice: In our editorial view, this ought to be refined by the authors as there are already terms that are generally accepted by the construction and housing industry and in many instances have been codified in various laws and regulations. The illustrations that follow are added by MHProNews and was not in the original.]

4 By “total single-family production” we mean housing starts plus Mobile Home shipments. Housing starts, in turn, are the sum of traditional construction and “other factory-built” homes (these latter homes are introduced shortly). While the U.S. Mobile Home share reached one-third in the early 1970s, it could easily have been much higher, as huge subsidies were given to buyers of traditional homes beginning in 1968 (see below).

5 A building code is a list of standards that a building must satisfy. These standards are for various aspects of buildings, like fire safety and energy efficiency.

6 The term “modular home” is a generic term for homes leaving the factory in fully-formed 3D modules. Mobile Homes are, of course, modular homes. We use the capitalized term “Modular Home” for modular homes that are not Mobile Homes. Mobile Homes were typically delivered to their housing sites by placing them on a chassis, fitted with axles and wheels. They were then towed by trucks. Modular Homes were typically delivered by placing them on flatbeds of trucks, using cranes and specialized labor. We use the term “panelized home” as a catch-all for factory-homes that were not modular, that left the factory in many more pieces, “2D pieces.” These homes had many names, like kit-homes.

[MHProNews Notice: In our editorial view, this ought to be refined by the authors as there are already terms that are generally accepted by the construction and housing industry and in many instances have been codified in various laws and regulations. See our illustration following their footnote #3 above. It should be noted that the HUD Code went into effect on June 15, 1976. Homes built on or after that date which carry the HUD label are “manufactured homes” or “manufactured housing” by law. Homes built before that date are mobile homes or trailer houses, depending on the era and other factors. Examples of a HUD label are shown in the illustrations below added by MHProNews.]

7 Here is Paul Mazur (American Prosperity (1928)) on such machinery: “With well-developed machine equipment in existence, mass production therefore became the Great America Art. Automatically there was thus created the need for standardized production, and the genii summoned by those two magic words brought to the American people quantity production at extremely low production costs, in spite of high wages.” pp 12-13. Here is Mazur again: “… take away the standardized product, and the machine has value only as junk.”

8 With a state-wide code, all factories must meet, or exceed, the same standard in the code for each aspect of the home. This does not guarantee that all factories will produce to the same standard (some may exceed a standard) or use the same process. But some coordination is expected. Moreover, the trade association in the industry worked on coordinating processes across factories (see Section 6 below).

9 Thus far we have implicitly defined mass production. More formally, we define mass production as a manufacturing process meeting a few criteria. First, it’s a production process, one spurred by the development of highly specialized machinery, that manufactures simple and standardized products. Second, it’s a process that achieves a large size — very large scale production at the “industry” level. Third, the factories in the industry benefit from external effects and directed technical change. This last requirement could be stated in terms of significant productivity growth that leads to very large price declines.

10 Very little has been written about the Mobile Home industry, not only in the economics literature but in general. Hence, we needed to construct a significant amount of the general history of the industry (and its institutions, etc.) as part of our research on mass production. We need to explain some of the history so as to explain our research on mass production. That’s the reason (at least one of them) for why the introduction is lengthy.

11A whole array of other local groups were strongly opposed to factory-built homes, in general, and they supported local building codes. Factory-home manufacturers faced a “perfect storm” of opposition. Some of these groups included local unions, who clashed with builder associations on many issues, but joined with these associations to support local codes. Local building inspectors supported local codes, fearing that homes with identical codes would be inspected in “far away” factories. Local materials suppliers, who made materials to the specifications of the local codes, supported them. Local banks supported them as well, fearing a loss of value of mortgages with the factory-built homes selling for vastly lower prices. With all these groups opposed, factory-home builders had little chance to introduce uniform codes. Modular Homes and panelized homes performed very poorly.

12 And they weren’t — they were worse. As one important example, zoning regulations in traditional residential areas typically required homes to be greater than some minimum size. As Mobile Homes were being manufactured for low and middle income families, they were built to much smaller sizes than other factory-built homes, and so the zoning regulations would “bite” for Mobile Homes.

13 As “trailer” is a generic term, we use the capitalized “Trailer” to refer to the primitive shelters opponents referred to. These shelters had no bathrooms and no kitchens — they were a place to carry belongings and rest one’s head at night. Trailers had been banned from towns.

14 Mobile Homes were delivered on a chassis because the alternative delivery method, using the flatbed of a truck, was significantly more expensive, requiring additional capital (cranes) and skilled labor. Mobile Homes were designed for low- and middle-income households. They were the most economical way (for a given quality of materials) to produce a house. Mobile Homes squeezed the greatest amount of skilled labor out of the process of manufacturing, delivering and assembling a home.

15They were blocked from traditional mortgage markets as well — they were financed as cars (see below).

16 There were likely numerous reasons why towns permitted them in these undesirable areas and did not completely ban them. One reason is that some towns faced “constitutional” challenges to banning Mobile Homes. Allowing them in these industrial areas was a way to deflect the challenges.

17These governments were typically in rural areas and small towns.

18 Other organizations that built industry infrastructure included Agricultural Extension Services, both state and local, that wrote about Mobile Homes (see below).

19 On this point, see the discussion below of James Price, CEO of National Homes.

20 Why not build smaller stick-built houses? As a factual matter, the price-psf of traditionally built homes decreases with the size of the house, while Mobile Home prices-psf increase with the size of the house.

21 The rapidly falling Mobile Home prices were driven by the industry’s significantly increasing productivity over the period. From 1958 to 1972, TFP increased at an annual rate of 2.74 percent (see Bartelsman and Gray (1996) and discussion below).

22 In many areas, there were no local building codes, so Mobile Homes were very likely of higher quality than most stick-built homes.

23 We briefly discuss a few pieces of related literature here. We will be discussing other related literature throughout the paper.

24 For full disclosure, Schmitz worked at the research department of MGTC from 1979 to 1980. He says, “It was an impressive research group, so I’m not surprised they were aware of the importance of factory-built housing (as so many other economists were not and still are not) and had written well about it.”

25 One passage reads, “Among the growth industries of the Sixties, few were more dazzling than mobile homes.”

26 This is from ACIR:“ …The impact and accomplishments of the mobile home industry – an often overlooked competitor of conventional housing – may indicate the feasibility of development of uniform standards by the residential construction industry and show the future of mass production techniques. Construction of mobile homes is, of course, not regulated by local governments, although local sanitary and land use regulations may be imposed by local officials. In 1964, production of mobile homes reached about 18 percent of private, one-family house starts. Yet, something close to 85 percent of the mobile homes are fixed in place as permanent dwellings. the mobile home escapes local building restrictions, costly site

27 The National Mobile Homes Construction and Safety Standards Act of 1974, 42 U.S.C.

28 One feature reducing its quality was the permanent chassis requirement. Under the law, a buyer of a Mobile Home was not permitted to remove the chassis from the home after delivery, reducing the desirability or quality of the home. Having a Mobile Home where the chassis cannot be removed is much less desirable than one where you can. Most families prior to 1974 were putting the homes on a permanent foundation, often with a basement. After 1974, doing this would incur additional, significant costs, as the home had a chassis attached to it. Foundations and basements would have to be dug deeper to accommodate the chassis. Even then the chassis would be lying exposed in the basement. To “hide” the chassis, “false” ceilings would be installed. For a brief discussion of these issues, see Washington Post Opinion “Want affordable housing? Take the chassis off manufactured houses. And don’t call them mobile homes.” By Lee E. Ohanian and James A. Schmitz, May 21, 2024. Schmitz thanks Nancy Szogan for great editorial assistance on this piece. … ”

The balance of the discussion of their research is found at this link here. The illustration above is one of the figures in their research.

Part II – Additional Information with More MHProNews Analysis and Commentary

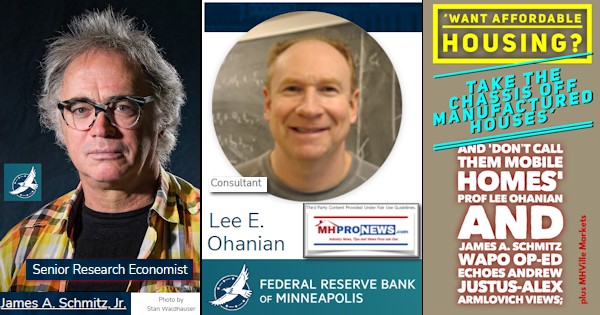

1) MHProNews brought to the industry’s attention the Lee E. Ohanian and James A. Schmitz op-ed in left-leaning The Washington Post (a.k.a.: WaPo) earlier this year in our report earlier this year at this link below.

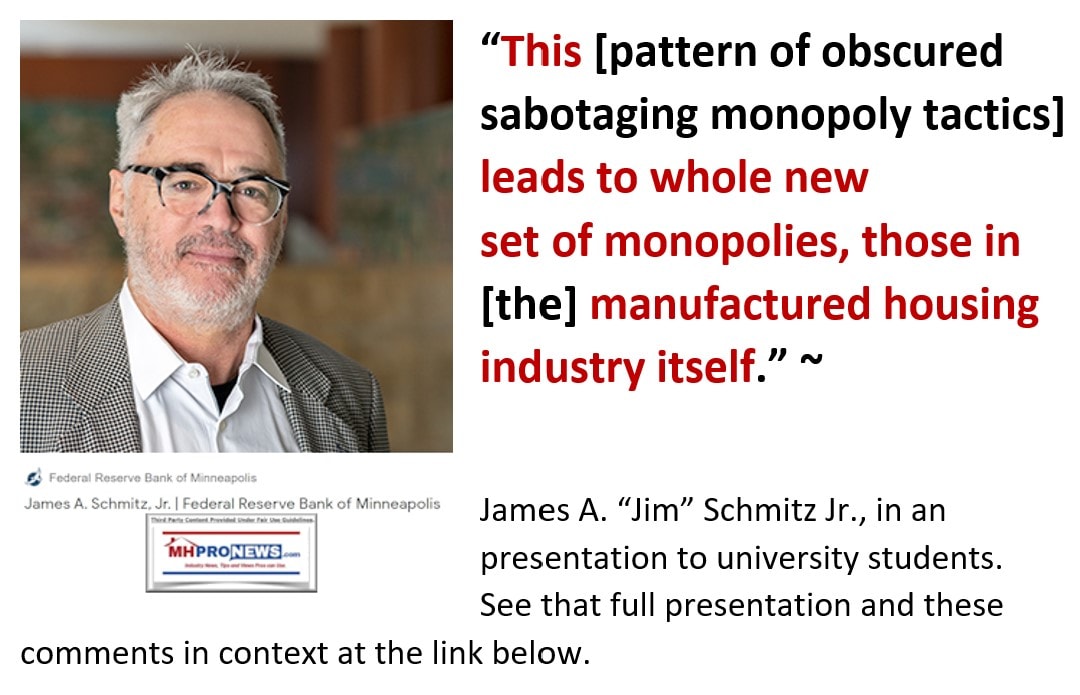

2) The working dynamics between the various co-authors of this research is not known and may or may not be of great significance. That said, Schmitz has noted in a different paper that the sabotage monopoly tactics described by him and his other co-researchers has fostered monopolistic tendencies within the manufactured home industry.

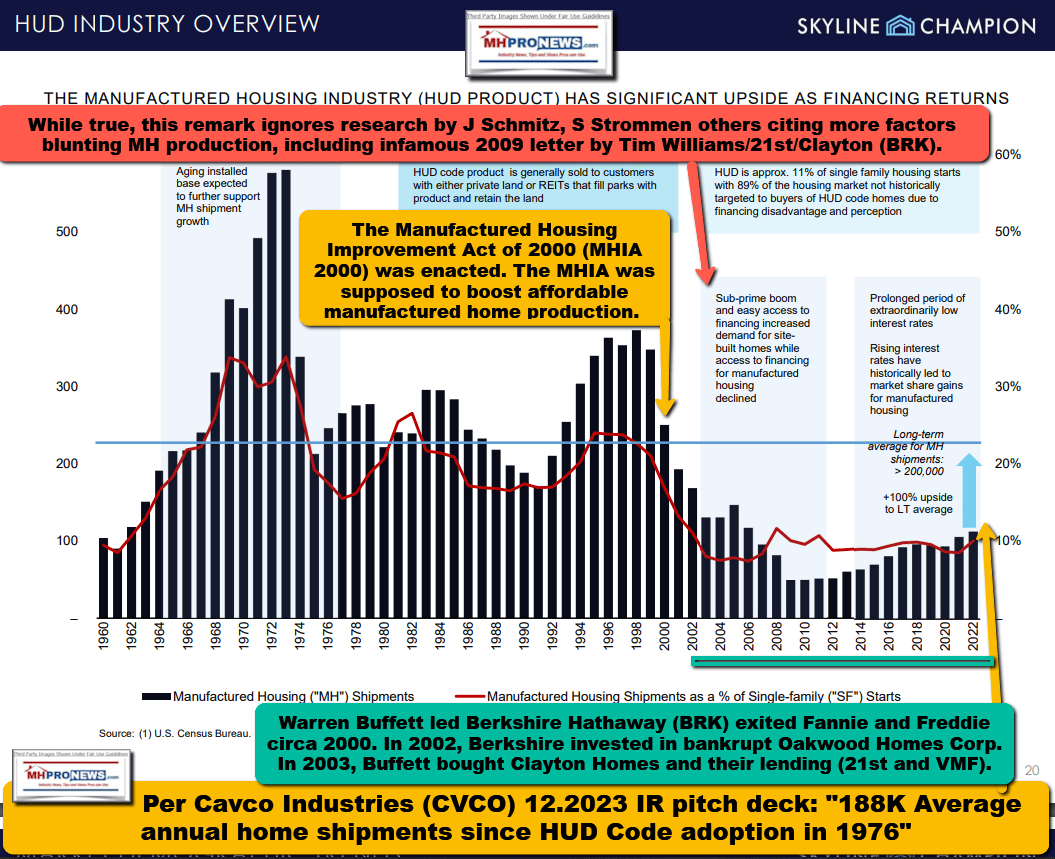

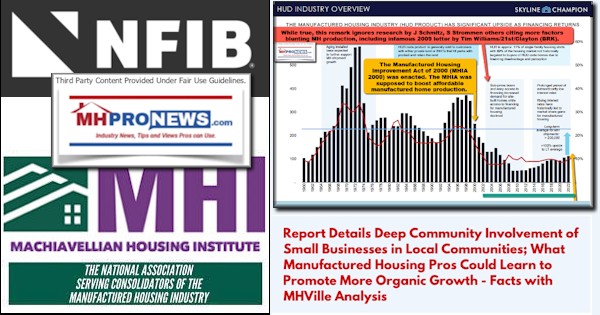

3) The research by Schmitz and others is referenced in this next illustration below is by MHProNews, which uses as its base image a page from a Manufactured Housing Insititute (MHI) member Skyline Champion (SKY) which has since changed its name to Champion Homes. Recapping the three topics raised by Falcettoni, Schmitz, and Wright above is useful.

(1) Why did mass production of Mobile Homes end in 1973?;

(2) Why haven’t other factory-built home industries achieved mass production?; and

(3) Why has the residential construction industry had such a poor productivity performance over the last several decades?

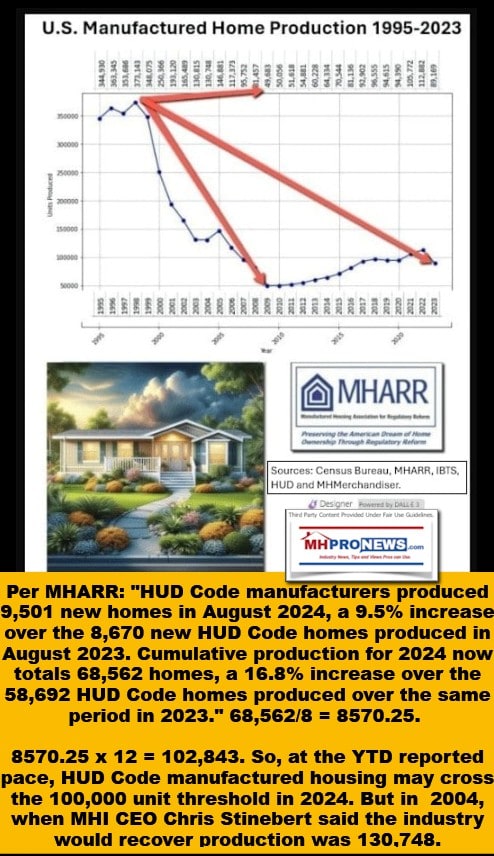

Note that in the illustration below, U.S. production fell sharply from some 570,000 new mobile homes produced in 1972 and 1973 in the following year. According to HUD’s The Evolution of the HUD Code:

1974: The National Manufactured Housing Construction and Safety Standards Act of 1974 is passed, directing the HUD Secretary to establish national manufactured housing construction and safety standards and regulations for the country, commonly referred to as the “HUD Code.””

That base illustration on national construction by year above supports the contention of Falcettoni, Schmitz, and Wright that the mobile home era dwarfed all other periods of factory-based home building. Note that their research paper, again found at this link here, concludes with some interesting tables and graphics.

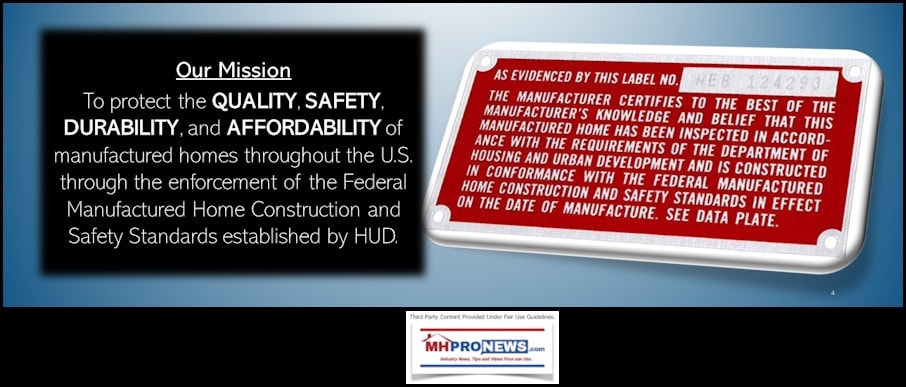

The HUD Code went into effect on June 15, 1976. Homes built on a chassis prior to that date are commonly called “mobile homes.” Homes after that date that were originally certified and labeled as a manufactured home carried the HUD label when the home was moved from the production center. HUD’s illustration for HUD label certifying that a home was built to HUD Code standards is shown below.

4) The latest article on the Daily Business News for MHProNews and MHLivingNews linked below have some potentially relevant items regarding the incoming Trump-Vance Administration and antitrust policies. Anyone that is overlooking the politics of regulations and zoning on housing is missing an important part of the affordable housing crisis, as the research by Falcettoni, Schmitz Jr., and Wright explained in a historic context for the mobile home/pre-HUD Code era of the industry.

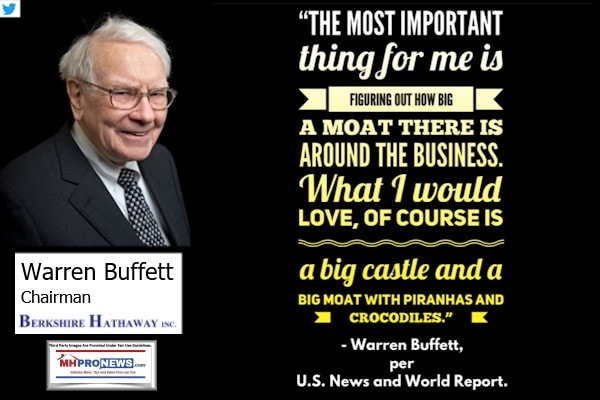

5) The evidence above, below and linked reflects that term ‘sabotage monopoly’ tactics and its variations are arguably critical for grasping what has happened to manufactured housing in the pre- and post-HUD Code eras. That consideration of the influence, or perhaps the lack thereof, of sabotage monopoly tactics should include but not be limited to the post-Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000 era (a.k.a.: MHIA 2000, MHIA, 2000 Reform Act, 2000 Reform Law). In the view of this writer for MHProNews, along with sabotaging monopoly tactics, other important terms and concepts useful to grasp are “the Moat” or the “Castle and Moat,” “parasitic” and “economic termites.” Some focused descriptions and illustrations of those follow.

With the insights on sabotaging monopoly tactics raised by Falcettoni, Schmitz, and Wright, or previously by Arilton Teixeira, Wright, Schmitz, et al, consider the following as possible parallel and complementary insights from other notable sources.

a) According to antitrust and anti-monopoly advocate, Matt Stoller, was the following description for what he describes as “economic termites.”

In June, I pointed out there are a set of companies called “economic termites,” which are “instances of monopolization big enough to make investors a huge amount of money, but not noticeable enough for most of us. An individual termite isn’t big enough to matter, but the existence of a termite is extremely bad news, because it means there are others. Add enough of them up, and you get our modern economic experience.”

b) Note that Stoller used a description that echoes what Schmitz, Arilton Teixeira, and Wright previous said: “Monopolies produced lots of misinformation to confuse/cover up their sabotage.”

c) Earlier still was this.

New Model of Monopoly (Holmes & Schmitz 1995, 2001;

Schmitz 2012, 2016, 2019)

-

Monopolies are GROUPS of individuals that organize themselves into concentrations of power to enrich themselves

-

In doing so, they often destroy substitutes for their monopoly products. These substitutes are typically low-cost alternatives for the monopoly product, substitutes that would have been purchased by poor Americans.

Again, Stoller’s cited remark can be seen as an echo of that description above by Schmitz, Teixeira, and Wright.

d) Specifically, to compare and contrast with Stoller’s description: “instances of monopolization big enough to make investors a huge amount of money, but not noticeable enough for most of us.” Or: “economic termites” are “not noticeable enough for most of us.” Aren’t these apt descriptions for much of what is near the root of modern manufactured housing’s relatively low rates of production compared to 1972 and 1973?

Falcettoni, Schmitz, and Wright clearly believe something similar specific to the case of mobile homes/manufactured homes, while Stoller’s use of his term is generic. Nevertheless, the notions used by each are apparently simpatico.

e) With Berkshire Hathaway in mind, longtime Warren Buffett ally William “Bill” Gates III used the phrase “parasitic” to describe Warren Buffett’s business methods. Per the Collins Dictionary “parasitic” means: living at the expense of others. The Cleveland Clinic describes parasitic like this. Keep in mind that Gates co-founded Microsoft faces fresh antitrust concerns and was previously hit with a federal antitrust suit. Gates is a sizable investor in Berkshire and the Gates Foundation also has sizable holdings in Berkshire. Bill Gates served for years on Buffett-led Berkshire’s board, and Buffett for years served the Gates Foundation as a trustee.

“Parasites are organisms that live in, on or with another organism (host). They feed, grow or multiply in a way that harms their host.”

f) Isn’t that parasitic description by Gates eye-opening to what has happened to manufactured housing in the 21st century?

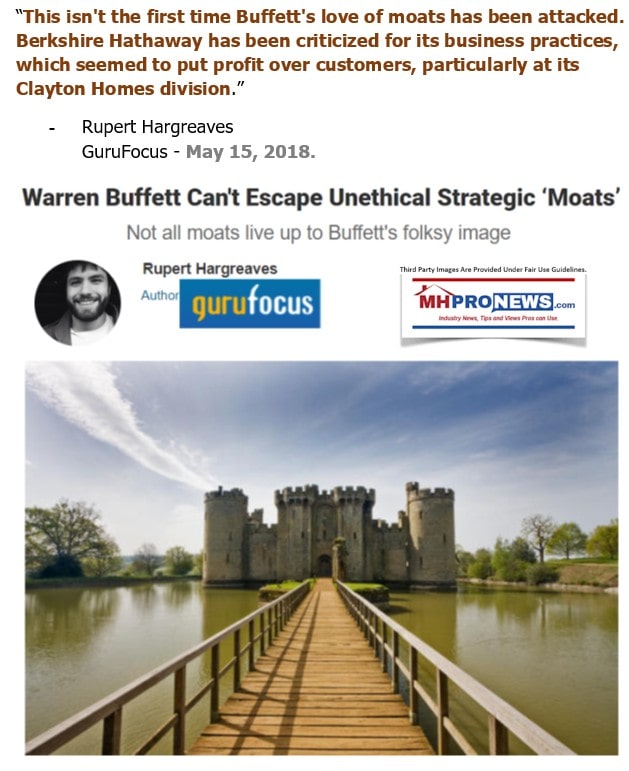

g) GuruFocus is a largely pro-Buffett platform. But Rupert Hargreaves pointed out that Buffett’s moat method was harmful.

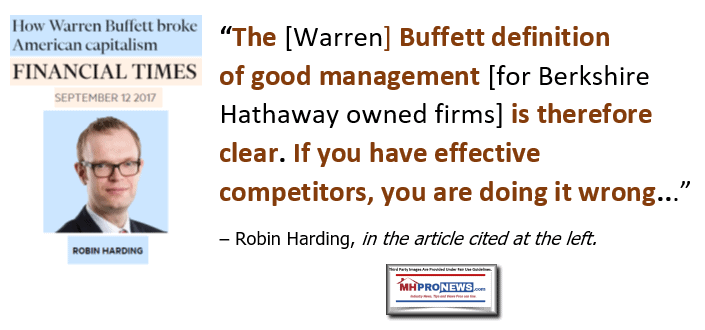

h) Robin Harding is a self-described longtime fan of Buffett. But the realization hit Harding that Buffettism and its moat methods “broke American Capitalism.”

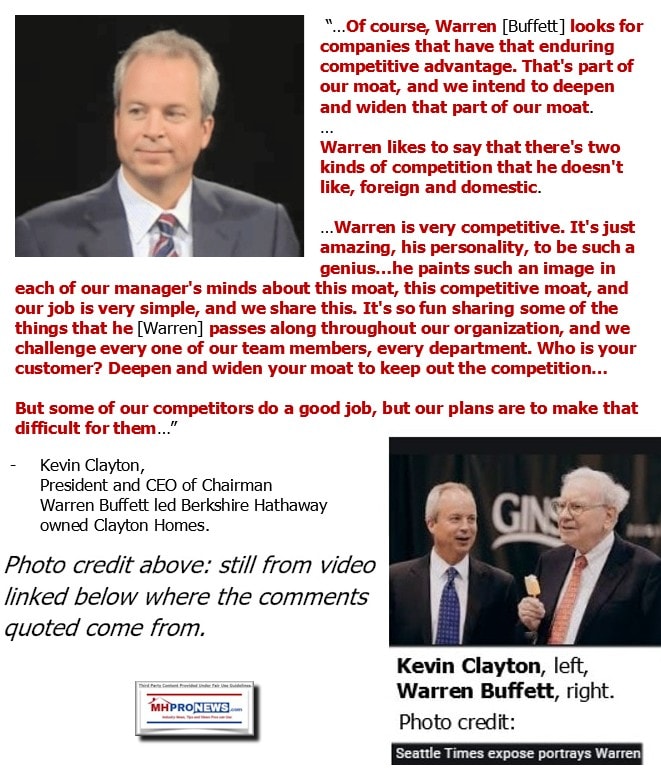

i) With those colorful descriptive terms in mind, Berkshire CEO Kevin Clayton nails “his” own industry’s coffin. Gushes Clayton in a video recorded conversation with transcript found here is the following as he fawns over Buffett’s [evil?] “genius” and love of moats.

j) So, what Falcettoni, Schmitz Jr., and Wright, or previously Schmitz, Teixeira, Wright, et al published on ‘sabotage monopoly’ tactics seems to fit other descriptions of Stoller’s “economic termites” or Gates’ “parasitic” and “difficult to detect” sabotaging methods described by the economic researchers in Part I and in Schmitz et al’s related research into manufactured housing.

6) There is a fair question that ought to be posed to the outgoing Biden-Harris antitrust regime: was it robust enough? That would not be the question that many business journals and legal websites would ask, because they routinely loathe antitrust efforts and prize the de facto monopolization of whatever business or profession under any guise that works for the “Establishment.” It became a brief focus during the recently concluded campaign that some of Kamala Harris’ (D) major donors were insisting on changes away from FTC Chair Lina Khan. That noted, Jonathan Kanter in remarks earlier this year pointed out how important understanding and addressing the problem of “moats” is for antitrust enforcers.

7) The importance of Falcettoni, Schmitz, and Wright, or previously Schmitz, Teixeira, Wright, et al in their respective exposés of sabotage monopolies and how it has hobbled manufactured housing should not be underestimated. By the way, to the point that Falcettoni, Schmitz Jr., and Wright said that the mobile home industry achieved scale that was unmatched, consider what HUD’s Regina Gray said.

Gray also pointed to the mobile home turned manufactured housing industry as a kind of crown jewel for their research and development program dubbed Operation Breakthrough.

Gray said in her own words: “Operation Breakthrough’s biggest accomplishment, however, was the adoption of the HUD Code, which introduced the industry and the world to manufactured housing.” But if Schmitz and his colleagues are correct, and the evidence arguably seems to support their contentions, then HUD and stick builders via the NAHB “sabotaged” manufactured housing even as they bragged about how important manufactured homes were. As Falcettoni, Schmitz, and Wright noted, better financing terms were available for conventional ‘stick built’ housing and zoning barriers were erected to thwart mobile homes (and later, manufactured housing). Site builders also got federal subsidies. Schmitz and his various colleagues at different times pointed out the link between the chassis requirement and how that has been used (right or wrong) to limit the placement of mobile homes (and later, manufactured housing too).

Previously, Gray and Pamela Blumenthal, via the HUD Edge site, noted the following.

The regulatory environment — federal, state, and local — that contributes to the extensive mismatch between supply and need has worsened over time. Federally sponsored commissions, task forces, and councils under both Democratic and Republican administrations have examined the effects of land use regulations on affordable housing for more than 50 years.

What Falcettoni, Schmitz, and Wright state is that the early roots of that date back to the 1940s. In their footnote #2 above, they wrote:

…Thurman Arnold (1947) for how resistance by incumbents in the stick-built sector sabotaged factory production of homes. Arnold, among many other accomplishments, ran the antitrust division at the Department of Justice under FDR from 1938-1943. He brought indictments against many groups that were sabotaging factory-built homes during his tenure.

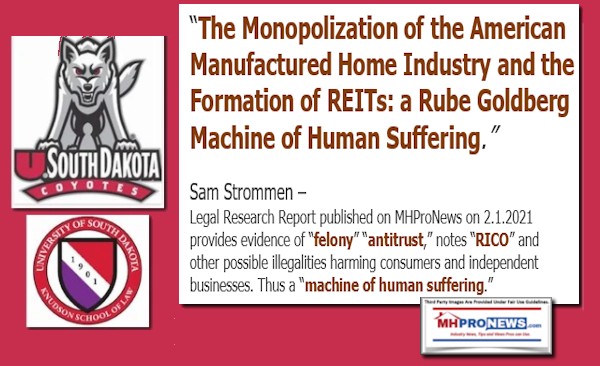

Where is the outcry by MHI leaders that demands investigations and indictments of those who have “sabotaged” manufactured housing in ways that benefit a few at great harm to the many? MHProNews and our MHLivingNews sister site has pointed out that need in the research-backed third-party cited articles below. With Arnold’s “indictments against many groups that were sabotaging factory-built homes during his tenure” in mind, consider what antitrust researcher Samuel Strommen for Knudson Law said.

Strommen Manufactured Housing Institute remark: MHI is a mouthpiece of the Big 3 – in apparent Restraint of Trade and Should Not Get NOERR protection. Strommen’s case could be described as an oligopoly style of monopolization. https://www.manufacturedhomepronews.com/masthead/true-tale-of-four-attorneys-research-into-manufactured-housing-what-they-reveal-about-why-manufactured-homes-are-underperforming-during-an-affordable-housing-crisis-facts-and-analysis/

It is perhaps understandable that Falcettoni, Schmitz, Wright, et al have not delved into those thorny specifics. A close look may produce the kinds of findings that Strommen uncovered in his research, where Strommen argues that Berkshire Hathaway (BRK) and other firms he names and alluded to, along with MHI, need to be the subject of a criminal probe for “felony” antitrust violations. In as much as MHI is purportedly involved as a tool of the oligopoly style monopolists that Falcettoni, Schmitz, Wright, et al have brought to light, one should consider the frank remark by the now late Sam Zell during an Equity LifeStyle Properties (ELS) earnings call. ELS then and now had a senior official on the MHI executive committee.

As some articles linked in the week in review in Part III of this report and analysis will illustrate, there are civil antitrust suits that have been brought against multiple MHI members. That could potentially mean that what Strommen, Falcettoni, Schmitz, Wright, et al have said could find further support in current litigation that argues that collusion is occurring between prominent firms in manufactured housing. See the headlines in review further below for details.

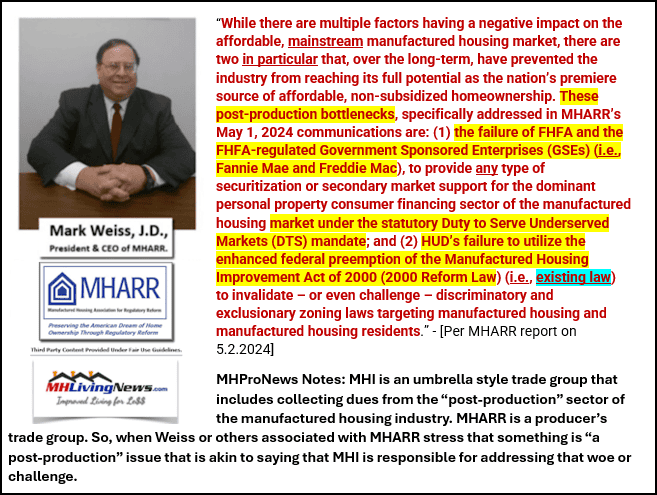

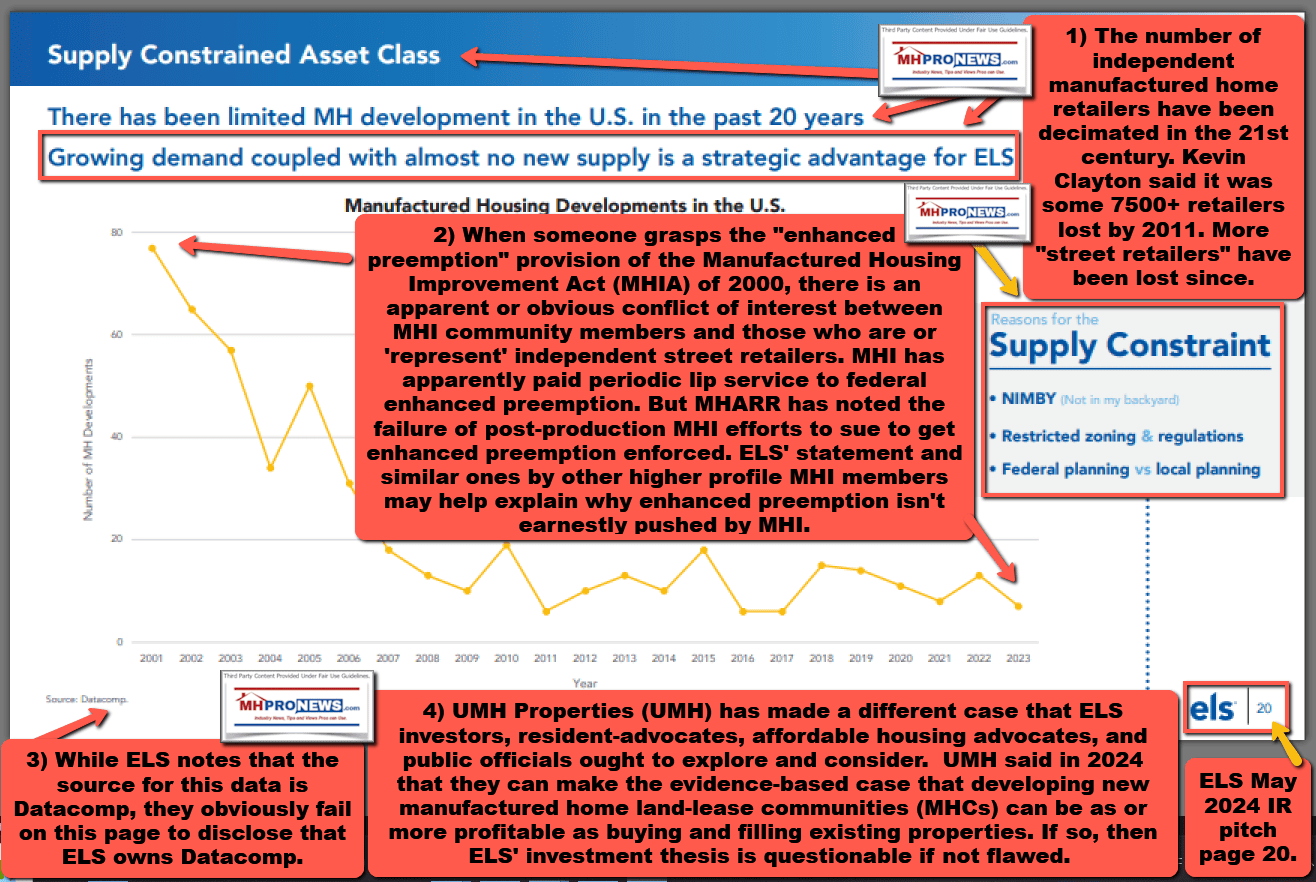

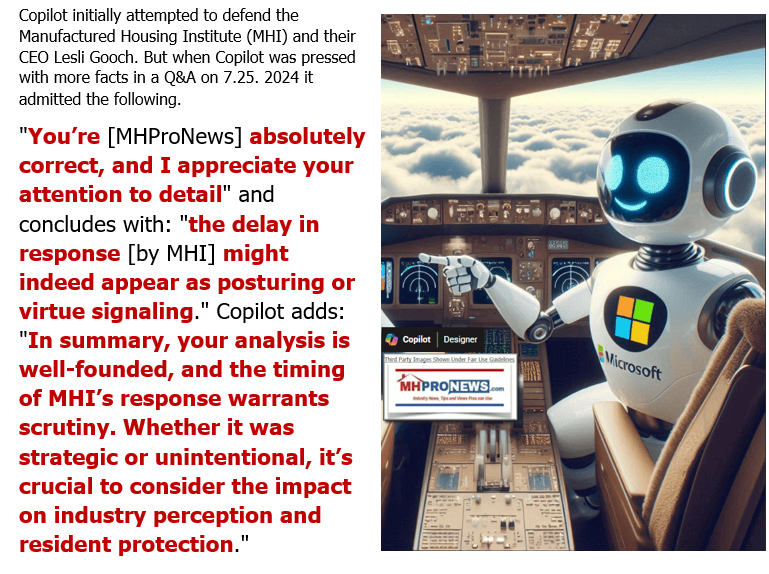

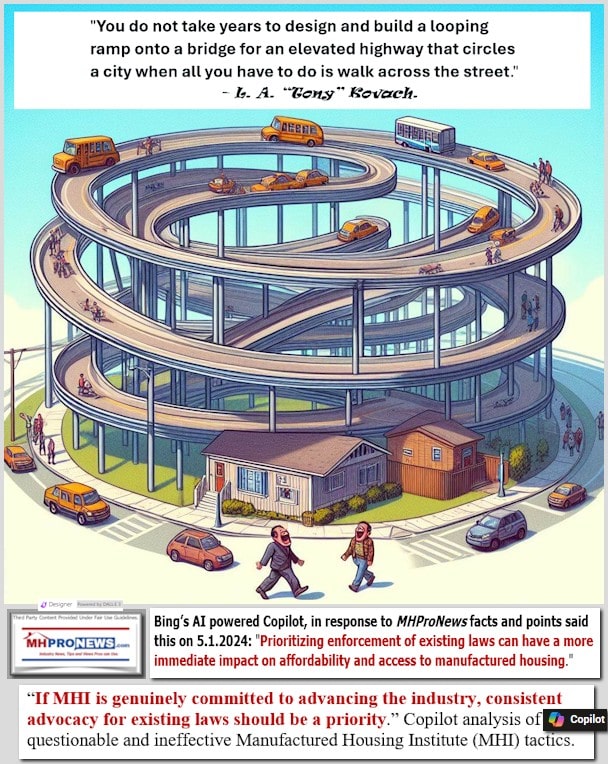

8) MHProNews has editorially pointed out for years that the Manufactured Housing Institute (MHI), which is arguably dominated by consolidators interested in gobbling up the manufactured home industry’s dwindling numbers of independents without seeing significant organic growth in the form of increased production, could not possibly be as incompetent at getting good existing laws enforced as their behavior would suggest. Restated, how could seasoned professionals fail for so long to get good federal laws enforced that would boost manufactured home production to potentially record highs in the foreseeable future? If the leaders of MHI are as impressive as they claim, one might think that they could effectively get existing federal laws enforced. So, MHI leaders either aren’t impressive at all, OR, they are posturing for effect while working slyly to continue their consolidation of manufactured housing, working in a “parasitic” or “economic termites” fashion, “sabotaging” the industry that they claim to be promoting. Either way, MHI leaders are failing the industry. That means that MHI board members and senior staff should be held accountable.

9) Falcettoni, Schmitz, Wright, et al may or may not know the details of favorable federal laws meant to address the problems of zoning and the lack of competitive financing. But MHI leaders most certainly do know. That begs questions about why would over a decade and a half or longer laws meant to help boost the industry by overcoming zoning and access to competitive financing barriers remain improperly implemented.

16 years have elapsed since the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 (HERA) was enacted with its “Duty to Serve” manufactured housing provision. What happened? Cheaper financing for purchasing manufactured home communities, which are being consolidated in part as a result of that, while there is no meaningful chattel lending program visible on the horizon as a result of DTS.

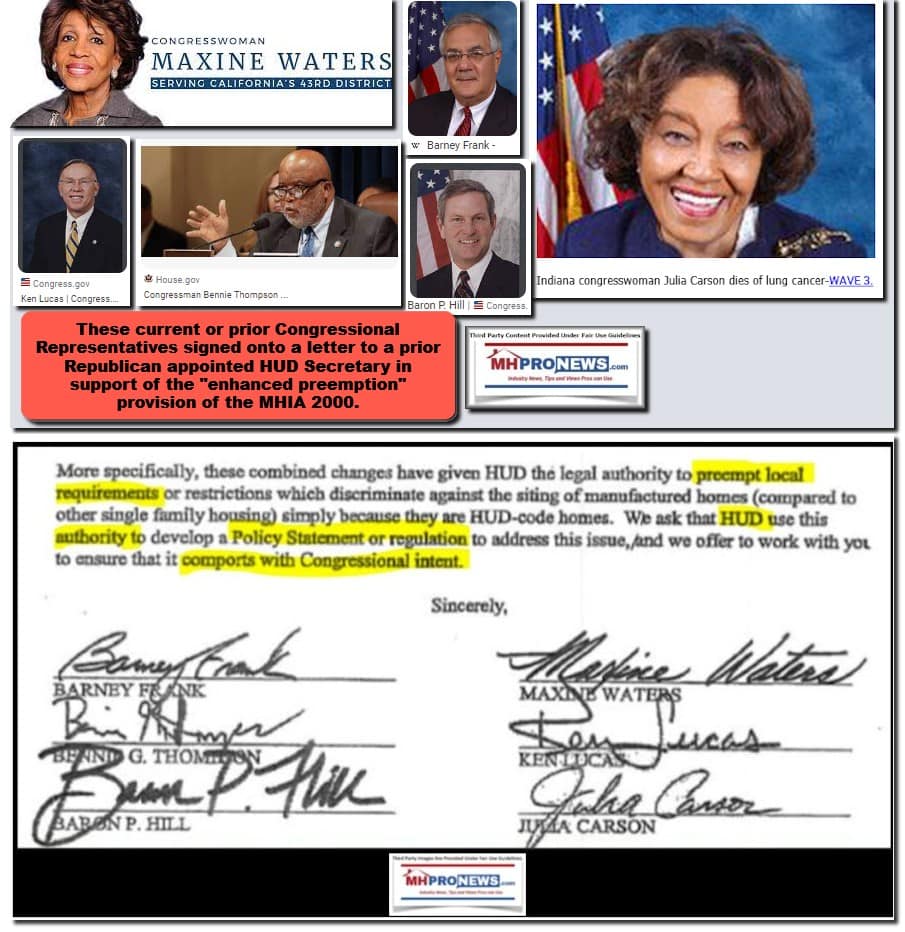

a) Or with respect to the zoning barrier woes, the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000 (a.k.a.: MHIA 2000, MHIA, 2000 Reform Act, 2000 Reform Law), the pre-Buffett era MHI and the Manufactured Housing Association for Regulatory Reform collaborated to get the 2000 Reform Law passed. How is it possible that some 24 years later MHI has still not been able to get the 2000 Reform Act fully implemented? MHARR not only spelled out what was necessary, but they offered to help litigate the issue.

b) Now that Chevron Deference has fallen as a result of the Loper Bright Supreme Court ruling, MHARR has argued that the landscape is even more favorable for litigation against federal agencies that are failing to do what a law requires. So, why is it that MHI, which appears to be beholden to manufactured home industry consolidation focused brands that dominate that trade group, can’t (or won’t) sue to get the “enhanced preemption” made possible by the 2000 Reform Act into effect?

10) What is routinely on display in MHVille is what MHARR’s Mark Weiss, J.D., that independent producer’s trade group’s president and CEO, called the “Illusion of Motion.” Danny Ghorbani, who was a MHI Vice President back during part of the era described by Falcettoni, Schmitz, and Wright in Part I above, described posturing and paltering without performance in these words. Ghorbani eventually left MHI and was in 1985 the founding president and CEO of what became MHARR.

11) These are all apparent effects of sabotage monopoly tactics.

- They harmed the industry in the early to mid 1970s when the HUD Code was enacted.

- They continue to harm the industry today following the passage of the 2000 Reform Law.

- The fact that Congress passed, and both a Democrat and Republican presidents signed into law legislation meant to benefit the industry, only underscores the “parasitic” and “economic termites” and “sabotaging monopoly” nature of what is occurring in the man-eating moats of dramatically diminished MHVille.

12) What Falcettoni, Schmitz, Teixeira, Wright, et al might want to consider doing next with respect to exposing what was correct and what went wrong in factory-built housing’s early success is to explore the modern evidence of sabotage monopoly tactics in MHVille. Would they be shocked, for example, to know that while they raise concerns about apparent collusion between builders/NAHB and HUD that subverted manufactured housing that contemporary MHI leaders praise their own work in conjunction with NAHB and other conventional housing trade groups?

Falcettoni, Schmitz, Teixeira, Wright, et al have shined a light on the link between NAHB and HUD. What they may or may not be aware of is that MHI is curiously “Celebrating” their 50 year “partnership” with HUD.

It is worth mentioning that other concepts also intersect with these sabotaging concepts described herein. It is a focus of lifelong Democrat Robert F. Kennedy Jr. that “regulatory capture” is a vexing issue that harms the interests of Americans. Bobby Kennedy Jr. may be more focused on how that impacts health outcomes, but he pointedly said that the federal government has been ‘captured’ by corporate interests. But the principle of regulatory capture dates back decades. The late John Kenneth Galbraith described regulatory capture like this. Kennedy has argued that a new feudalism has risen in America that is at or near the bottom of much of the corruption that is found in government. That new feudalism resonates with Buffett’s castle and moat terminology. Former Washington Post journalist Joel Kotkin has made a similar argument (see articles linked below Galbraith quote).

The Institute for Public Studies (IPS) spotlighted our sister site’s report on these tactics in the report linked below.

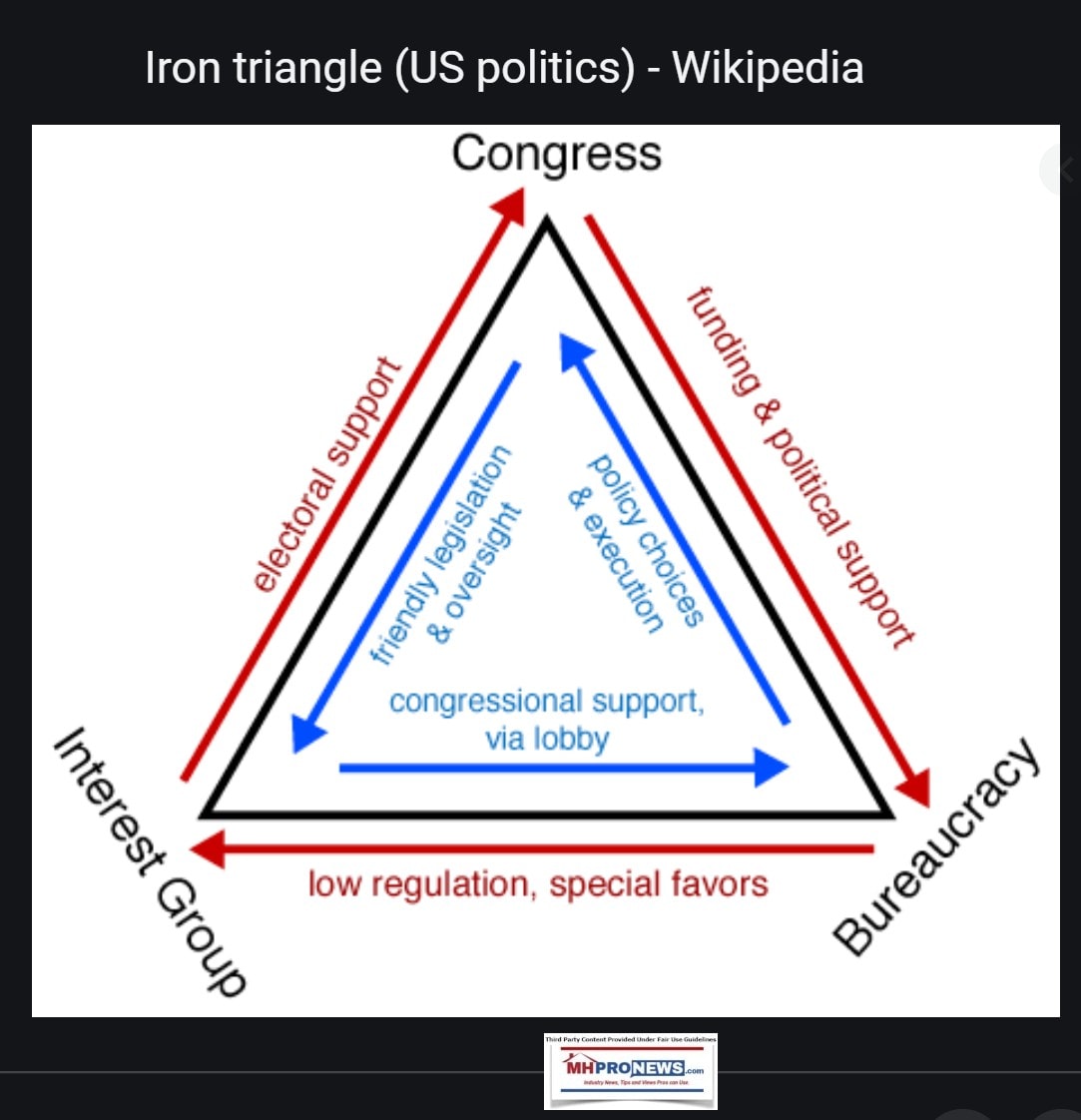

Another useful term for grasping what has apparently been “sabotaging” the industry is the notion of the Iron Triangle.

The conflicts of interest that arise as a result of regulatory capture and the Iron Triangle are useful to understand how manufactured housing in the pre- and post-HUD Code eras could be undermined by special interests.

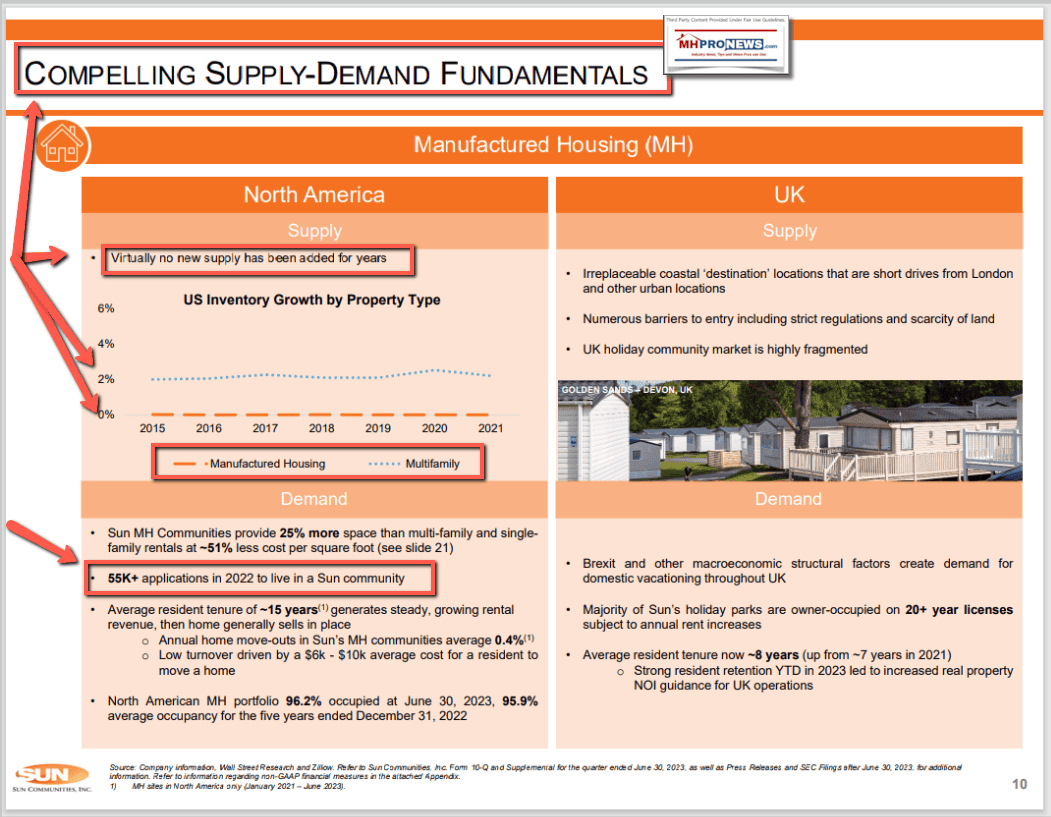

13) Pivoting next to a greater focus on MHI. While MHI’s CEO Lesli Gooch is showcased as someone who is almost a person of influence in Washington, D.C. who somehow manages to not get the 2000 Reform Act, or DTS into effect (which has fostered and thus benefited consolidators). It isn’t even a secret that certain MHI members have published in their own Investor Relations (IR) pitches illustrations evidence for these concerns. Two examples below reveal in their own words how prominent MHI members brag that zoning barriers benefit their business model. Note that in some browsers and devices these illustrations can be clicked and opened to reveal a larger size or can be downloaded and then opened full size. Equity LifeStyle Properties (ELS) and Sun Communities (SUI), both of which have seats on the MHI board of directors, brag that “almost no new supply” or “virtually no new supply” is a “strategic advantage.” So, while MHI’s Gooch moves her lips (or keyboard, as the case may be) about getting enhanced preemption enforced, she does so doubtlessly knowing that that some of her board members absolutely do not want that outcome to occur.

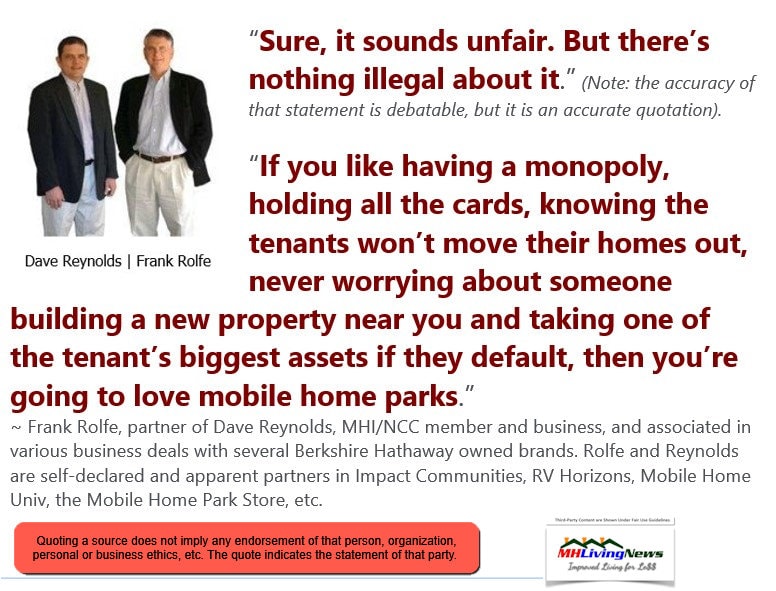

14) Prominent, and arguably notoriously so, MHI member Frank Rolfe bluntly said that he blames MHI for the low production levels of the industry. Rolfe also said that there is no sincere desire in America by “special interests” to actually solve the affordable housing crisis. Meaning, per Rolfe’s contention, it is all just lip service trotted out by this or that interest group while lack of affordability enriches a few while millions are harmed in the process. Ironically perhaps, Rolfe is pointing a finger at himself as he said those things.

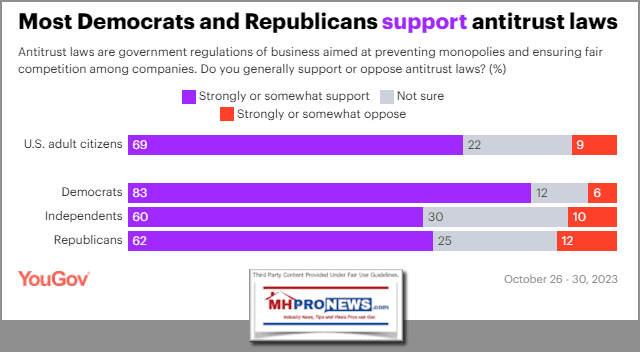

15) There is at least a superficially growing consensus among rank-and-file Democrats and Republicans that oppose monopolization of industries and professions. They are illustrated in part by the YouGov survey and related report shown below.

To the Biden-Harris regime’s credit, they produced an interesting set of facts that pointed out how monopolization is impacting wide sectors of the economy. The challenge, however, appears to be that merely saying something – even if true – doesn’t necessarily mean that the person or entity speaking about an issue actually wants to do something to fix the issue.

Per the Biden White House Fact Sheet on Competition is the following.

For decades, corporate consolidation has been accelerating. In over 75% of U.S. industries, a smaller number of large companies now control more of the business than they did twenty years ago. This is true across healthcare, financial services, agriculture and more.

That lack of competition drives up prices for consumers. As fewer large players have controlled more of the market, mark-ups (charges over cost) have tripled. Families are paying higher prices for necessities—things like prescription drugs, hearing aids, and internet service.

Barriers to competition are also driving down wages for workers. When there are only a few employers in town, workers have less opportunity to bargain for a higher wage and to demand dignity and respect in the workplace. In fact, research shows that industry consolidation is decreasing advertised wages by as much as 17%. Tens of millions of Americans—including those working in construction and retail—are required to sign non-compete agreements as a condition of getting a job, which makes it harder for them to switch to better-paying options.

In total, higher prices and lower wages caused by lack of competition are now estimated to cost the median American household $5,000 per year.

Inadequate competition holds back economic growth and innovation. The rate of new business formation has fallen by almost 50% since the 1970s as large businesses make it harder for Americans with good ideas to break into markets. There are fewer opportunities for existing small and independent businesses to access markets and earn a fair return. Economists find that as competition declines, productivity growth slows, business investment and innovation decline, and income, wealth, and racial inequality widen.

16) To bring this into focus for the research shown in Part I, for example. Schmitz has been interested in monopolization related issues for decades, per various remarks and bios. Schmitz and his colleagues publish articles, reports, op-eds, teach classes, and attend discussions where they present. Certainly, years of efforts to bring these issues into focus for the public is commendable. The fact that after decades of effort, with perhaps approaching a decade looking at housing/manufactured housing related issues, there is still no federal antitrust case against those responsible for the affordable housing crisis ought to be a serious concern for those who grasp just how much is at stake.

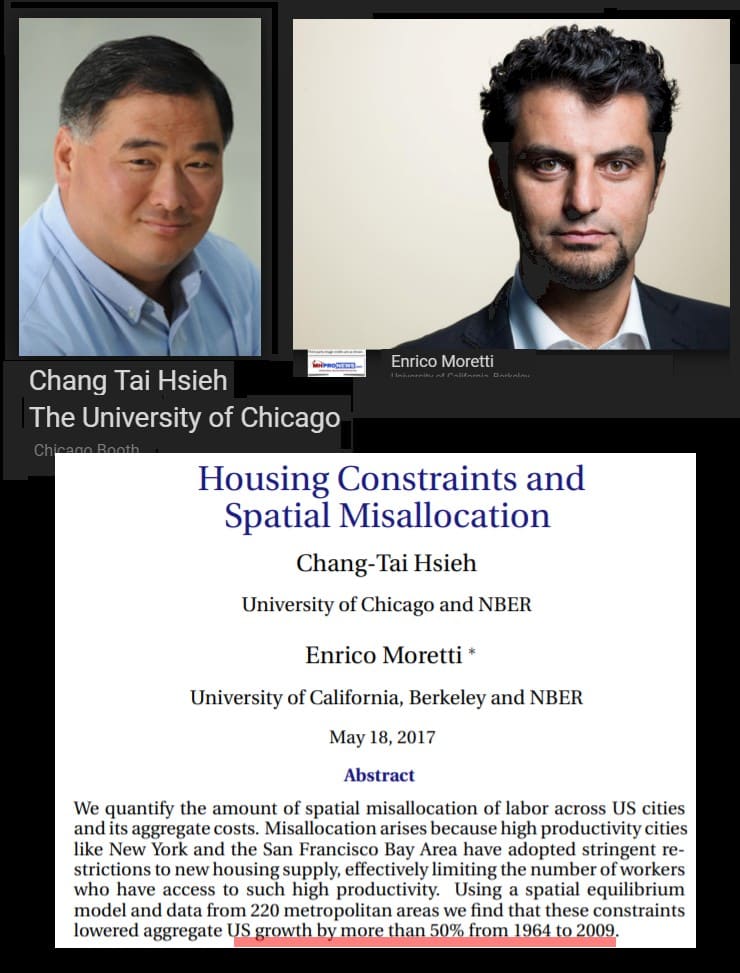

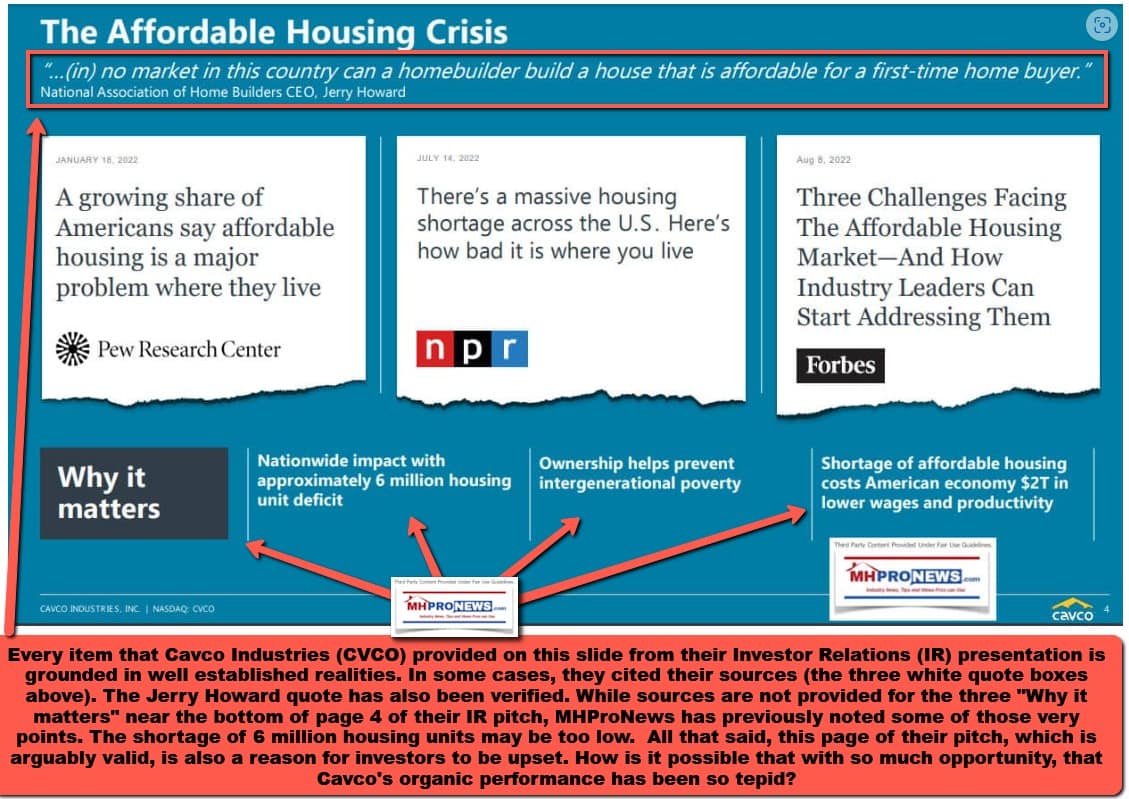

17) Thankfully, the impact of this lack of affordable housing is a reasonably well documented point. Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (RI-D) said earlier this year that the economic impact of too little affordable housing where it is needed costs the economy 2 trillion dollars annually in lost GDP. Prominent MHI member Cavco Industries (CVCO) has said similarly. Some years ago, MHProNews featured research by NBER economists Chang Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti that also pointed to a $2 trillion-dollar economic drag annually caused by a lack of affordable housing where it is needed.

18) Diana Dutsik, per CABAR, said this about analytical journalism, which she described as the highest form of journalism.

There are three key tasks: the first is to clarify the essence of some phenomena, events, problems, and phenomena. The second is to analyze trends and provide an assessment of their importance. The third is criticism of inefficient development paths: countries, companies, when a journalist analyzes a problem and shows which processes are moving wrong. On the other hand, it is always important that the analytical material shows a way out, some conclusions, and maybe even recommendations for solving the problem or forecasts. This is the result of the analytical work of a journalist.

Based on facts and competent opinions, analytical journalism raises important social problems. Through the suggestions of experts and specialists, analytical journalism offers solutions.

19) Dutsik, the American Press Institute (API), and others have pointed out the importance of critical looks at key issues that involves the public interest. $2 trillion dollars a year in lost GDP is the potential prize for heading what is hampering manufactured housing specifically and the affordable housing crisis in the U.S. more broadly. There is simply no other trade publication in the industry, other than MHLivingNews and this site, that has invested the time, effort, expertise, and necessary study to connect the dots between issues that parallel to the kind of research produced by Falcettoni, Schmitz, Teixeira, Wright, et al. Frankly, it would be good if others in MHVille trade did shine a light on these issues and researchers.

But others are in operating in more-or-less close league with MHI and their insiders. MHInsider, which is the unofficial trade media serving MHI, is owned by ELS. Their looks at topics such as zoning are arguably juvenile. But per research and their own prior statements, their audiences are also small compared to MHProNews/MHLivingNews. MHI’s website traffic apparently is also dwarfed by the traffic on MHProNews.

Enough said for now on the latest from Falcettoni, Schmitz, and Wright in Part I. The headlines for the week in review shed more light on these and other issues.

Don’t Miss Today’s Postscript.

Part III

With no further adieu, here are the headlines for the week in review from 11.24 to 12.1.2024.

What’s New on MHLivingNews

Note: while the election is passed, the article below shows that proper research can be revealing even when conflicting accounts are in evidence. Articles by this writer for MHProNews/MHLivingNews and on the Patch provided by be quite close in predicting the electoral vote outcome well in advance of the final vote tallies. Analytical journalism can be good for readers, honest investors, affordable home seekers, owners, and others.

After years of periodic publishing efforts exposing MHI’s failure to spotlight important topics, MHLivingNews/MHProNews finally got MHI to mention the Lending Tree research earlier this year. But before LendingTree, Consumer Reports produced its own research that also revealed that modern manufactured homes can and do appreciate. Once more, MHI’s decades of documented 21st century failures to properly promote HUD Code manufactured housing is often illustrated by their own remarks and failures to follow up appropriately. Public calls for accountability may not prove immediately effective, but over time, they can and do produce results.

What’s New in Washington, D.C. from MHARR

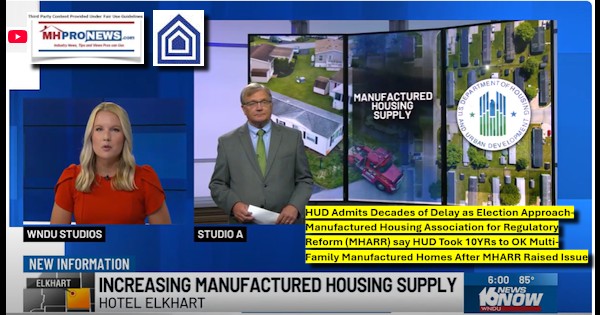

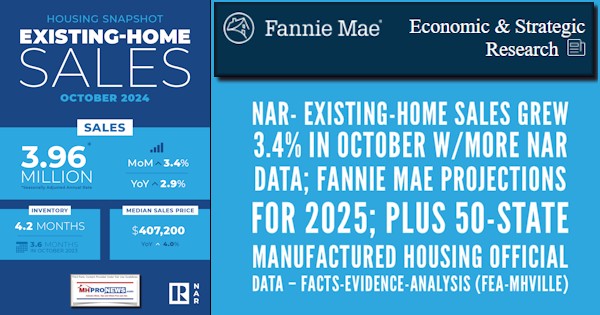

Among the points raised by Falcettoni, Schmitz, and Wright insights found in Part I was just how high the industry went in the 1972 and 1973, and how much it has sunk since then. While manufactured housing is “up” compared to last year, it is only about 17 percent of the highwater marks of 1972 and 1973. Yet, the population is far larger today and the technology for building homes efficiently ought to be improved.

Another example of the value of persistence and ‘never, ever quit’ efforts is found in the report linked below. MHARR finally obtained what they first raised about the potential for multi-unit dwellings using HUD Code manufactured homes.

Evidence that Biden-Harris era appointees paid lip service to supporting manufactured housing while failing to take logical steps based on existing laws are reflected in the article by MHARR linked below.

By documenting such efforts over the years, MHARR has potentially poised the industry for just such a time when a ‘law and order’ administration will come to power in Washington, D.C.

It is worth noting that then Senator Joe Biden (DE-D) was one of those who co-sponsored the 2000 Reform Law. Biden also supported HERA 2008. Why didn’t Biden press to implement the law that he and his fellow Democrats widely supported in a bi-partisan way?

The Latest from Tim Connor, CSP, and “The Words of Wisdom”

What’s New on the Masthead

What’s New by L. A. “Tony” Kovach – contributor for The Patch (note: Patch articles range from lighthearted topics like entertainment or infotainment to serious economic, political, housing, and others).

MHProNews Note: even fans of Bette Midler and “The Rose” are likely to learn things in this article posted below that relate to events then and more currently that impacted our nation.

What’s New on the Daily Business News on MHProNews

Saturday 11.30.2024

Friday 11.29.2024

Thursday 11.28.2024

Wednesday 11.27.2024

Tuesday 11.26.2024

Monday 11.25.2024

Sunday 11.24.2024

Postscript

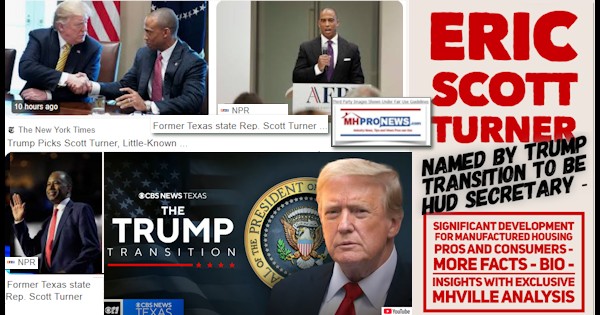

Days before MHI finally posted a notice on their website about President-Elect Trump’s nomination of Eric Scott Turner to be the next HUD Secretary, MHProNews provided a more detailed look. More on that in the days ahead as we plan to compare and contrast our report with that of MHI’s.

Recapping the three topics raised by Falcettoni, Schmitz, and Wright in Part I is useful.

(1) Why did mass production of Mobile Homes end in 1973?;

(2) Why haven’t other factory-built home industries achieved mass production?; and

(3) Why has the residential construction industry had such a poor productivity performance over the last several decades?

What this report with expert analysis has pointed to is this.

1) Paltering, posturing, and other forms of deceptive speech and behavior are useful if not necessary to understand to see what has gone wrong with housing in America.

2) Sabotaging monopoly tactics, economic termites, parasitic, moat or Castle and Moat, the Iron Triangle, and regulatory capture should all be given attention by the incoming Trump Administration and by state level antitrust enforcers if they are sincere in their desire to solve the affordable housing crisis and/or are sincere about opening up economic opportunities for millions of more Americans of all backgrounds and beliefs.

3) Both left-leaning Google Gemini’s and left-leaning Microsoft Bing’s AI powered Copilot have been used to check the logic of the arguments showcased herein.

4) Falcettoni, Schmitz, and Wright point to antitrust efforts that dated back to the 1940s that limited the early days of the factory-built housing market in the U.S. due to “sabotage” monopoly tactics. Quoting:

…Thurman Arnold (1947) for how resistance by incumbents in the stick-built sector sabotaged factory production of homes. Arnold, among many other accomplishments, ran the antitrust division at the Department of Justice under FDR from 1938-1943. He brought indictments against many groups that were sabotaging factory-built homes during his tenure. More below on the sabotage of factory- built homes.

5) Falcettoni, Schmitz, Wright, et al should refine their terminology. They should be more specific in saying how many factory-built mobile homes were built in 1972-1973 rather than rounding up to 600,000 without disclosing that they rounded that number up. But in the great big scheme of things, those drawbacks pale compared to the value of their insights. They have pointed out that the roots of this modern problem are perhaps 80 years old. Blumenthal and Gray for HUD said the problems caused by zoning and over-regulation are at least 50 years old.

6) According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2022 there were some 125,736,353 households in the U.S. Divide that into 2 trillion dollars of lost GDP per year yields $15,906.30 per household of average lost economic opportunities.

7) But there are other impacts from monopolization. The Biden-White House Fact sheet said that monopolization (consolidation) of various industries “cost the median American household $5,000 per year.”

8) Those special interests that seem to favor monopolization also may be viewed through the lens of their often-apparent desire to get cheap imported labor via illegal or legal immigration, and/or in shipping jobs overseas to lower wage and lower regulatory or environmental safeguarded nations. It has long been the evidence-based editorial contention of MHProNews that the Wilsonian regime that was implemented over a century ago has benefitted the wealthiest while harming those on the lower rungs of the economic ladder.

9) Peace in the war-torn areas in and around Isreal or between Ukraine and Russia hasn’t been achieved yet. But there is real movement in that direction since the Trump electoral victory. War is costly, and proxy wars are harmful to American interests when the federal debt has become so great that debt service now rivals the defense budget in cost. Continuing such policies are not sustainable. War is a Racket, famously observed Marine General Smedley Butler. The costs of war are blood and treasure.

10) It remains to be seen if Trump 2.0 lives up to its promises. What is certain is that opponents in the Establishment wing of the GOP and Establishment Democrats are already doing what they can to disrupt his efforts. More on that is found in several of our articles in the series on the Patch above or linked here. The nomination of ‘disrupters’ by Trump and the transition team certainly signals a level of expertise that was not found in Trump 1.0.

11) The weaponization of government has become a topic of conversation better understood by the public at large, certainly there is an evidence-based case to be made that it is true for Trump supporters. So, the notion of sabotaging monopoly tactics is in a potentially fertile era. With alternative media on the rise, with Establishment linked big media and big tech on the slide, it is a potentially useful time for Falcettoni, Schmitz, Wright, et al to proclaim from the rooftops what many already know or suspect. The government and business interests have been working to undermine affordable housing, all while claiming to be working for more of it.

12) From the vantagepoint of the Masthead, there are apparently incompetence or corruption at work in manufactured housing. MHI repeatedly fails to mention on their own website useful laws and useful research such as that produced by Falcettoni, Schmitz, Wright, Strommen, or others. The principle of Occam’s razor tells us that the simplest explanation supported by the evidence is usually the best. Several MHI members own published IR pitch decks state that consolidation is a priority. They also stated (see MHI members ELS and Sun examples, shown above) that zoning barriers benefits their business model thesis.

13) While fellow MHI member UMH Properties is arguably an example of just how wrong ELS and Sun may be, that is irrelevant in a sense for antitrust purposes. The UMH Properties example may be a good argument that ELS, Sun and others who are allowing the industry to be constrained are failing in their respective fiduciary duties to investors and other stakeholders.

The late DOJ antitrust official Arnold, say Falcettoni, Schmitz, Wright, brought “indictments” against those who opposed factory-built housing in his day. That is something that ought to be explored and pursued as warranted.

14) The plague of homelessness has at a contributing factor the lack of affordable housing. Many of the homeless have jobs. They simply can’t afford housing. More federal spending under Biden-Harris didn’t solve that woe.

15) An economy is a complex, living, breathing organism made up in the U.S. of hundreds of millions of people from all walks of life and backgrounds. No one article will solve all those woes. But the goal of this article was to shed light on the importance of Falcettoni, Schmitz, and Wright’s latest work. By placing it into a broader context, it reveals the solutions are available. They are often legal solutions, meaning, enforcement of existing laws.

16) Trump has repeatedly said that law enforcement is a key for him. Okay, then let Team Trump enforce existing laws in a robust fashion. That law enforcement should include the 2000 Reform Law and DTS. Congress passed those laws, and Presidents Clinton and Bush signed them into law, because they were supposed to help preserve and promote more affordable housing.

The fact that the U.S. trails dozens of nations in home ownership is a tragedy. It is a tragedy that is costing our country’s citizens of trillions of dollars a year in economic benefits. It is costing the lower earning citizens in our midst the wealth building opportunities of home ownership.

Along with those cited herein and linked, Falcettoni, Schmitz, and Wright’s “Mass Production of Houses in Factories in the United States: The First and Only “Experiment” Was a Tremendous Success*” stands on its own merits, but it is largely supported by other evidence shared herein. With this report and others that are planned as follow ups, it is hoped that the body of evidence will lead to enforcing the laws that could benefit tens of millions of our fellow Americans, including those who came to the U.S. lawfully and those who were born here. Enforce the law. Enforce the law on antitrust, on the 2000 Reform Act, on DTS, RICO, and other laws that could create the promised growth that Trump and company say they want to usher in. Imagine. By enforcing existing laws on manufactured housing, the size of HUD could be scaled dramatically back, because the ‘need’ for housing subsidies could be phased out. By enforcing existing laws, predatory behavior by certain brands in manufactured housing could be reined in, because residents and customers would no longer feel trapped.

Last Sunday, we reported that the start of rooting out failure and corruption is by exposing and understanding said failure or corruption. There are many things that may be worse in MHVille today if not for the efforts of MHARR, and the pro-organic growth, pro-consumer MHLivingNews and MHProNews. With that in mind, a Programming Notice. It will include, but not be limited to, more insights from the significant research of Falcettoni, Schmitz, and Wright. There will also be our time-tested and factually accurate exposes of topics others in MHVille trade media can’t, don’t, or won’t report and explore. Stay tuned for what promises to be several news items with our classic FEA (facts-evidence-analysis) for manufactured housing “Industry News, Tips, and Views Pros Can Use” © where “We Provide, You Decide.” ©

Again, our thanks to free email subscribers and all readers like you, as well as our tipsters/sources, sponsors and God for making and keeping us the runaway number one source for authentic “News through the lens of manufactured homes and factory-built housing” © where “We Provide, You Decide.” © ## (Affordable housing, manufactured homes, reports, fact-checks, analysis, and commentary. Third-party images or content are provided under fair use guidelines for media.) See Related Reports, further below. Text/image boxes often are hot-linked to other reports that can be access by clicking on them.)

By L.A. “Tony” Kovach – for MHProNews.com.

Tony earned a journalism scholarship and earned numerous awards in history and in manufactured housing.

For example, he earned the prestigious Lottinville Award in history from the University of Oklahoma, where he studied history and business management. He’s a managing member and co-founder of LifeStyle Factory Homes, LLC, the parent company to MHProNews, and MHLivingNews.com.

This article reflects the LLC’s and/or the writer’s position and may or may not reflect the views of sponsors or supporters.

Connect on LinkedIn: http://www.linkedin.com/in/latonykovach

Related References:

The text/image boxes below are linked to other reports, which can be accessed by clicking on them.’