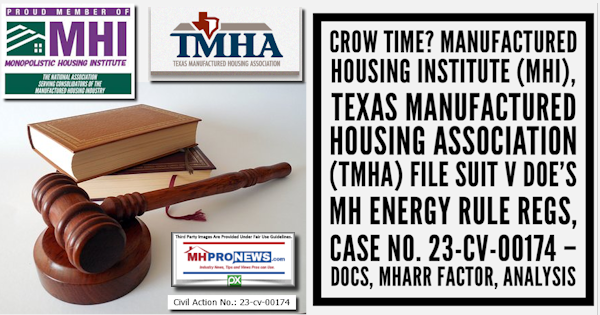

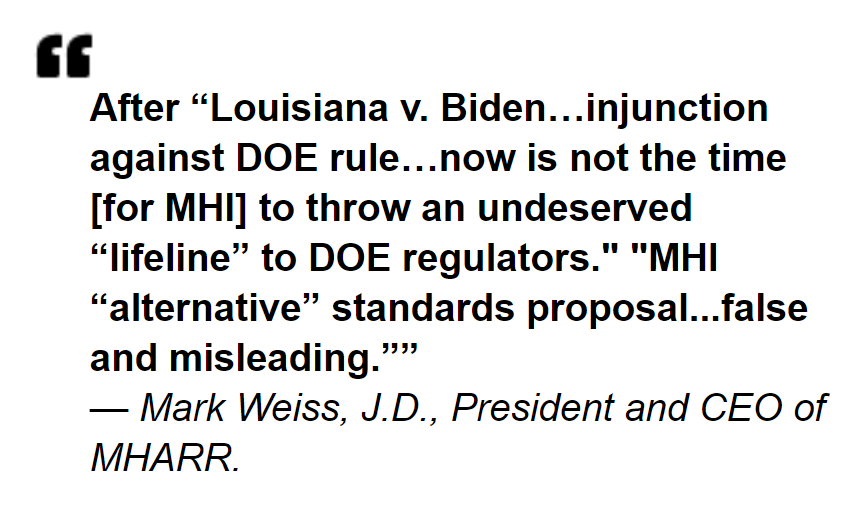

‘Happy Valentine’s Day’ to the Department of Energy was not mentioned in the Manufactured Housing Institute (MHI) legal pleadings opposing the Department of Energy (DOE) manufactured housing energy standard regulations in a suit filed in association with the Texas Manufactured Housing Association (TMHA). Nor were their pleadings’ pending filing mentioned in the MHI generated “Federated States” ‘newsletter’ to their ‘affiliated’ state associations emailed on 2.13.2023. The MHARR Factor – what a prior MHI chairman indicated was the ‘elephant in the room’ – will be explored herein as an influence on MHI and the TMHA’s potentially important step, as the Manufactured Housing Association for Regulatory Reform (MHARR) has been consistently calling for litigation by MHI since the DOE issued their ‘final rule’ last year. Similarly, this platform and our MHLivingNews sister site have consistently highlighted for months the lack of litigation by MHI on this and other nagging issues that are arguably harming manufactured housing industry producers, sellers, consumers, taxpayers, and others.

If MHI was more transparent in years gone by, those years have obviously since gone by. When MHI doesn’t inform their own readers/members/affiliates in writing through their emailed ‘newsletter’ the day before their suit is filed, well, shouldn’t that be flagged as a problem? More on that further below, in Part II of this report. Part II will include additional information with more facts, information and expert analysis in this Masthead editorial on MHProNews.

That noted, it is potentially a good thing that MHI has filed suit.

The MHI/TMHA pleadings include the claim that over 50,000 new manufactured homes may not be sold or built due to the pending DOE ‘final rule’ energy standards.

MHI’s outside attorneys argued that that the rule will harm minorities and all financially marginal buyers more than more affluent ones.

If successful, MHI should be given a qualified kudos. Either way, MHARR absolutely merits praise for exposing several of the apparently duplicitous steps taken by MHI, which MHProNews has consistently exposed to the largest professional trade audience in MHVille.

With that backdrop, and a promising potential pivot by MHI which suggests that they may finally be doing their job to represent “all segments” of manufactured housing, in Part I below are the main pleadings and the TRO (Temporary Restraining Order) filed against the DOE.

Part I.

a. MHI-TMHA primary federal court filing.

Case 1:23-cv-00174 Document 1 Filed 02/14/23 Page 1 of 46

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

)

THE MANUFACTURED HOUSING )

INSTITUTE; and THE TEXAS )

MANUFACTURED HOUSING )

ASSOCIATION, )

) Civil Action No.: 1:23-cv-00174

Plaintiffs, )

)

- )

)

THE UNITED STATES )

DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY; and )

JENNIFER M. GRANHOLM, )

Secretary of the United States )

Department of Energy in her official )

capacity only, )

)

Defendants. )

PLAINTIFFS’ ORIGINAL COMPLAINT SEEKING TEMPORARY AND PERMANENT DECLARATORY AND STAY/INJUNCTIVE RELIEF UNDER THE APA

TO THE HONORABLE UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE:

Plaintiffs the Manufactured Housing Institute (“MHI”) and the Texas Manufactured

Housing Association (“TMHA”), both trade associations representing all segments of the manufactured housing industry, bring this action for declaratory and injunctive relief.

SUMMARY

Plaintiffs challenge the Department of Energy’s (“DOE”) recent promulgation of energy standards for manufactured housing in its May 31, 2022 Final Rule, titled “Energy Conservation

Program: Energy Conservation Standards for Manufactured Housing.” 87 Fed. Reg. 32,728 (the “Final Rule”). Plaintiffs timely make this challenge in advance of the Final Rule’s upcoming May

31, 2023 compliance date, and contemporaneously with this Complaint file a Motion to Stay in accordance with 5 U.S.C. § 705 because that compliance date is arbitrary, capricious, and impracticable. DOE promulgated the Final Rule in contravention of its Congressional mandate to consult with HUD, the primary federal agency setting standards through an extensive regulatory structure, and which has over 50 years of experience regulating the manufactured housing industry.

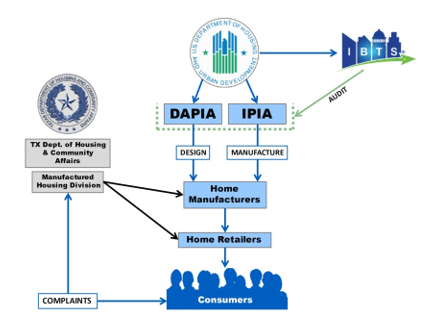

Some aspects of this regulatory structure are described infra and are illustrated as follows:

The manufactured housing industry is an avid proponent of energy conservation efforts.

The industry’s manufacturers are pioneers in the development of construction processes that value and prioritize energy efficiency. Manufacturers are constantly developing new initiatives and technologies, such as comprehensive recycling programs, to reduce waste. Through the controlled environment of the factory-built process, manufacturers are able to use exact dimensions and measurements for most building materials. Today’s modern manufacturing plants are so efficient that nearly everything is reused or recycled, including cardboard, plastic, carpet padding, vinyl siding, scrap wood and much more. Similarly, with regard to consumers, a recent study of residential energy consumption showed that existing manufactured homes consume the least energy of all types of homes. In 2020, more than 30% of new manufactured homes met or exceeded Energy Star efficiency standards.[1]

According to a recent Freddie Mac study, “[e]nergy efficiency built into the homes themselves and an eco-friendly manufacturing process mean manufactured homes far surpass sitebuilt in terms of their environmental footprint. The factory home building process produces a fraction of the waste compared to a site-built home.”[2]

While the manufactured housing industry as a whole is an active proponent of energy conservation and efficiency, to ensure that manufactured homes remain the most affordable, unsubsidized housing option in today’s market, energy standards must be accurately balanced against their implementation costs. The Final Rule falls woefully short of striking a rational balance between energy conservation and affordable housing. And DOE failed to comply with its requirement to consult with HUD. In sum, the Final Rule is contrary to the law and is in violation of both the Administrative Procedures Act (the “APA”), 5 U.S.C. § 551, et seq., and the Final

Rule’s enabling legislation, the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 (the “EISA”), 42 U.S.C. § 17071.

INTRODUCTION

- The Department of Energy regulates various aspects of the nation’s energy practices. In the EISA, Congress authorized DOE to “establish standards for energy efficiency in manufactured housing.” 42 U.S.C. § 17071(a)(1).

- In the Final Rule, DOE sought to carry out its mandate under the EISA to promulgate energy standards for manufactured housing. But DOE failed to comply with its legislative mandate under the EISA—and, moreover, DOE’s Final Rule is arbitrary and capricious in violation of the APA.

- First, in preparing the energy standards for manufactured housing, DOE failed to consider all relevant costs that affect the purchase price of manufactured homes and the total lifecycle construction and operating costs for consumers. The EISA explicitly directs DOE to ensure that its energy standards for manufactured housing are “cost-effective,” taking into account the standards’ impact “on the purchase price of manufactured housing and on total life-cycle construction and operating costs.” 42 U.S.C. § 17071(b)(1). Openly shirking this mandate, DOE readily admits in the Final Rule that it has “not included any potential associated costs of testing, compliance or enforcement at this time.” 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,758. Obviously, testing, compliance, and enforcement (and their associated costs) are integral to both energy standards and construction materials and techniques. Testing, compliance, and enforcement will indisputably and materially increase construction costs of manufactured homes and thereby the purchase price for each manufactured home. DOE wholly ignored these costs in direct contravention of the EISA. For example, potential costs of duct-leakage testing alone have been estimated to be as high as $1,500 per home, far above DOE’s original estimates of consumer savings for single-section and multi-

section homes over the 10-year analysis period.

- Relatedly, compliance with the Final Rule will require manufacturers to purchase substantial additional construction materials such as fiberglass insulation. DOE’s methodology has completely ignored recent economic realities including the actual costs of construction materials.

In 2022, DOE arbitrarily used outdated 2014 materials cost estimates (instead of recent and actual construction costs) and assumed a hypothetical nominal annual cost increase of 2.3% between 2014 and 2023. Even if this abstract economic model approach could be understandable in some ordinary times or in a college course, this assumption willfully ignores the realities of this remarkable decade and the current macro-economic factors. The DOE’s approach fails to comport with the dramatic actual cost increases to building and manufacturing materials caused by the

Covid-19 pandemic and a series of historic natural disaster events like hurricanes that have hit the United States since 2014 that have created massive economic disruptions to supply chains and home construction. As was well-known at the time DOE promulgated the Final Rule in May 2022, the cost of construction materials has actually increased by 6.5% annually between 2014 and 2021—driven mostly by cost increases of an astonishing 35.1% from 2020 to 2021. DOE wholly ignored these actual cost increases for construction materials contrary to its legislative mandate.

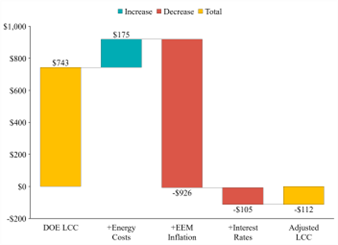

- For example, using DOE’s own modeling but accounting for actual economic realities, DOE’s conclusion of net benefits of $743 over a 10-year period to multi-section homebuyers is reversed, and Final Rule will result in a net cost of -$112 to the average multi section homebuyer over DOE’s 10-year analysis period. And nearly all (98 percent) of borrowers using a personal property loan to finance a multi-section home purchase would face net costs over a 10-year horizon.

- DOE also failed to account for the nation’s dire supply chain shortages and just

assumed, without any support, that all new materials would be readily available to manufacturers.

- The real consequences of the faulty assumptions and other problems with the

DOE’s methodology and non-compliance with the APA mean that the Final Rule—if allowed to be implemented and enforced by May of 2023—will cause substantial disruption to homebuyers and Plaintiffs’ members among many others. Based on purchase price increases, economists estimate that the Final Rule could lead to between 1,703 and 5,101 fewer manufactured home sales each year over the next ten years (for a total of between 17,030 and 51,010 fewer homes). Worse still, some number of those families may be left with no housing at all, exacerbating and compounding the nation’s affordable housing crisis. Equally as important, economists estimate that the Final Rule will disparately impact the lowest income and historically underrepresented groups by rendering home ownership even further from their reach.

- Second, the Final Rule is arbitrary and capricious in its one-year compliance deadline. In the Final Rule, DOE demands that manufacturers fully comply with its sweeping changes to energy standards by May 31, 2023, a mere one year after the date on which DOE published the new standards. This aggressively short compliance window is unrealistic and arbitrary. The Final Rule will require manufacturers across the manufactured housing industry to redesign every home model—of which there are thousands. Manufacturers must source the new materials required to comply with the Final Rule during a global supply chain crisis. It is patently unreasonable and unjust for DOE to demand these seismic industry shifts in just 12 months. DOE typically allows appliance manufacturers five (5) years to comply with new energy standards. Constructing an entire manufactured home is certainly more complicated than constructing an appliance.

- Third, in contravention of another of the EISA’s requirements and critical to the problems that have forced Plaintiffs to file this lawsuit, DOE failed to consult with HUD about the

Final Rule’s energy standards. The EISA required DOE to bring the specific standards it was contemplating to HUD so that DOE could benefit from HUD’s long-standing familiarity and expertise in regulating the construction and affordability of manufactured homes. DOE never did so. At best, in the Final Rule, DOE states in cursory fashion that it did “consult” with HUD. That perfunctory, conclusory claim is insufficient as a matter of law. The administrative record must reveal actual, substantive consultation with HUD in the development of DOE’s energy standards. Tellingly, in response to FOIA requests on behalf of Plaintiffs for any evidence of consultation, DOE has refused to produce any information at all, much less any information that could substantiate any manner in which DOE discharged its lawful obligations. Where, as here, there is no such evidence, the Final Rule should be set aside.

- DOE’s Final Rule has unnecessarily caused conflict with the leading federal agency involved in extensively regulating the manufactured home industry, HUD. In the Manufactured

Housing Improvement Act of 2000, Congress established the Manufactured Housing Consensus Committee (“MHCC”)—a statutory Federal Advisory Committee body charged with providing recommendations to the HUD Secretary on the revision and interpretation of HUD’s manufactured home construction and safety standards and related procedural and enforcement regulations.

Because of HUD’s long-standing experience in this area, the EISA required DOE to consult with

HUD. However, in promulgating the Final Rule, DOE did not consult with HUD or the MHCC. After DOE promulgated the Final Rule, in October and November of 2022, the MHCC convened to review and analyze the Final Rule, and concluded, inter alia, that:

- The MHCC has reviewed the DOE Final Rule and has determined DOE circumvented the standards development process prescribed in EISA which requires cost justification and consultation with HUD.

- DOE provided an energy conservation standard which was based on site built construction and applied it to a performance-based national code. If adopted as written, the Final Rule would adversely impact the entire

Manufactured Housing program and cost increases associated with

compliance would reduce prospective purchasers (especially minorities and low-income consumers) from durable, safe, high quality and affordable housing.

- The MHCC previously recommended that DOE include the substantial cost of testing, enforcement, and regulatory compliance in its costing analysis.

The Final Rule did not consider these costs.

MHCC Working Document from October and November 2022 MHCC Meetings, at 1–2 (emphasis

added).[3]

- The manufactured housing industry values improvements in energy efficiency. Indeed, the industry and its factory construction methods are at the forefront of such innovations. But the statutory mandate under which DOE promulgated its energy standards for manufactured housing quite sensibly requires that DOE balance energy efficiency together with other goals, chief among them the goal of ensuring that affordable housing is broadly available to those who would otherwise lack the ability to pursue homeownership. DOE’s Final Rule is out of step with, and in practice undermines, these goals. Indeed, if allowed to go into effect, as mentioned above, it will cause disproportionate harm to historically underrepresented groups within the manufactured housing market.

- Given these defects in DOE’s rulemaking, Plaintiffs ask this Court to declare that the Final Rule is unlawful, set aside the Final Rule, and stay or enjoin DOE from implementing it.

PARTIES

- Plaintiff MHI is the only national trade organization representing all segments of the factory-built housing industry. MHI’s members include home builders, retailers, community operators, lenders, suppliers, and affiliated state organizations. MHI’s members produce approximately 85% of the manufactured homes constructed each year. MHI is an Illinois not-for-profit corporation with headquarters in Arlington, Virginia.

- MHI works to promote fair laws and regulations, increase and improve financing options, provide technical analysis and research, promote industry professionalism, remove zoning barriers, and educate external audiences about the benefits of manufactured housing. Through these various programs and activities, MHI seeks to promote the use of manufactured housing to consumers, developers, lenders, community operators, insurers, the media and public officials so that more Americans can realize their dream of homeownership.

- MHI has a substantial interest in this action. MHI is focused on maintaining the affordability of manufactured housing to serve lower-income home purchasers. DOE’s Final Rule puts the affordable nature of manufactured housing at substantial risk because the Final Rule failed to consider the actual costs associated with implementation. Additionally, MHI is also focused on the stability of the manufactured housing industry, and the Final Rule introduces significant uncertainty to the industry. By way of example only, the Final Rule requires various new energy efficiency standards, but the Final Rule fails to offer any testing procedures for those standards. The manufactured housing industry faces grave uncertainty complying with energy standards when the industry does not know what testing procedures for those standards DOE will accept assatisfactory.

- Plaintiff TMHA has served Texas’ manufactured housing industry since 1952. TMHA is concerned with the entire scope of the Texas manufactured housing industry. The association represents over 1,400 company members from every facet of the industry, including manufacturers, retailers, communities, insurance companies, suppliers of goods and services, salespeople, real estate companies, title companies, developers, transporters, installers, financial institutions, brokers, and other affiliated companies. TMHA is a not-for-profit incorporated association organized and existing under the laws of the State of Texas, with its principal place of business located at 4520 Spicewood Springs Road, Austin, Travis County, Texas 78759.

- Texas is home to 26 manufactured housing construction facilities, which is the largest number of facilities in any single state. In 2021 alone, these Texas manufacturing housing facilities produced over 23,500 homes—approximately 22% of all manufactured homes produced in the country during that year.

- TMHA has a similar interest in this action as MHI. TMHA is also focused on maintaining the affordability of manufactured housing to serve lower-income home purchasers.

DOE’s Final Rule puts the affordable nature of manufactured housing at substantial risk because the Final Rule failed to consider the actual costs associated with implementation. Additionally, TMHA is focused on the stability of the manufactured housing industry given the number of plants located in Texas. The Final Rule introduces significant uncertainty for those plants. By way of example only, the Final Rule requires various new energy efficiency standards, but the Final Rule fails to offer any testing procedures for those standards. The Texas manufactured housing plants face grave uncertainty complying with energy standards when the Texas plants do not know what testing procedures for those standards DOE will accept as satisfactory.

- Both MHI and TMHA file this suit in a representative capacity for their members that are home manufacturers and are therefore subject to the Final Rule. Unless the Court grants relief from the Final Rule, MHI’s and TMHA’s members will suffer irreparable harm. Additionally, the interests that MHI and TMHA seek to vindicate in a representative capacity are germane to both MHI’s and TMHA’s associational purposes.

- Defendant the United States Department of Energy is a federal agency with headquarters at 1000 Independence Ave., SW, Washington, D.C. 20585. DOE issued the Final Rule.

- Defendant Jennifer M. Granholm is the Secretary of DOE and is ultimately responsible for DOE’s operations, including the development and implementation of the Final Rule. Secretary Granholm is sued in her official capacity only.

- Defendants may be served by delivering a copy of the summons and complaint to the United States attorney for the district where the action is brought, with a copy of each sent by registered or certified mail to the civil-process clerk at the United States attorney’s office and to the agency or officer against whom relief is sought. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 4(i).

JURISDICTION AND VENUE

- This action arises under the EISA and the APA. This Court has jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1331 and is authorized to grant declaratory relief under the Declaratory Judgment Act, 28 U.S.C. §§ 2201–02.

- This Court may hear this action under the APA because Plaintiffs seek review of a final agency action—the Final Rule—for which there is no other adequate remedy.

- Venue in this Court is proper under 28 U.S.C. § 1391(e) because Plaintiff TMHA resides in the district and no real property is involved in this action. “Courts have held that venue is proper as to all plaintiffs if suit is brought in a district where any one or more of the plaintiffs [4]” Crane v. Napolitano, 920 F. Supp. 2d 724, 746 (N.D. Tex. 2013), aff’d sub nom. Crane v. Johnson, 783 F.3d 244 (5th Cir. 2015).

BACKGROUND

I. The Manufactured Housing Industry

26. Manufactured housing is an indispensable part of the American housing market. Approximately 22 million Americans live in manufactured homes. In 2021 alone, the manufactured housing industry produced over 105,000 homes, which represented 9% of all new single-family home starts. That percentage is expected to increase going forward. Manufactured homes are significantly less expensive than traditional site-built homes and represent a critical part of the solution to the nation’s dire need for affordable housing.

27. The average consumer pays $72,600 for a single-section manufactured home and $132,000 for a multi-section manufactured home.4 In stark contrast, the average cost for a site built home is $365,904.[5] As of 2019, the United States had a housing deficit of 3,800,000 units, but that estimate has only increased after the Covid-19 pandemic.[6] As stated by Fannie Mae: “One solution to addressing the nation’s housing supply shortage is to build more homes. New factory built manufactured homes, which can be built as single- or multiple-section homes, appear to be significantly more affordable than site-built homes . . . . Factory-built manufactured homes meeting the HUD Code standard have substantially lower all-in monthly housing costs than site built homes. As a result, it is important to preserve this source of unsubsidized housing for lower- income residents. In addition, factory-built manufactured housing is an affordable option for buyers desiring a new home.”[7] New manufactured homes offer exceptional quality construction as well given that the construction standards for manufactured housing across the country are subject to robust compliance and quality assurance regulations, sometimes more stringent than those for traditional site-built homes.

28. The median household income for those who own manufactured homes is approximately $35,000 per year, far below the national average, and nearly one-half of the average income for site-built homeowners.[8] As DOE noted in the Final Rule, 60% of single-section manufactured home occupants and 45% of multi-section manufactured home occupants fall below 200% of the Federal Poverty Level. See 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,750. For a family of four, the 2022 Federal Poverty Level is $27,750 in annual income.[9] Similarly, the Consumer Protection Financial Bureau (“CFPB”) recently found that the median annual income for manufactured housing borrowers is between $52,000 and $53,000. See CFPB, Manufactured Housing Finance: New Insights from the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act Data (May 2021), at 34. For contrast, the median family income for the United States was approximately $90,000 in 2022.[10]

- Over 71% of purchasers cite affordability as a key reason they choose manufactured housing.11 Manufactured housing is the largest source of unsubsidized housing in the country.

- Manufactured homes are highly affordable because of efficiencies in the factorybuilding process. They are constructed with standard building materials and built almost entirely off-site in a factory. The controlled construction environment and assembly-line techniques eliminate many of the problems posed by traditional home construction, such as weather, theft, vandalism, damage to building products and materials, and unskilled labor. Factory employees are trained and managed more effectively and efficiently than the contracted labor used by the sitebuilt home construction industry.

- Manufactured housing supports the United States economy because manufactured homes are made in America. The manufactured housing industry includes approximately 35 domestic corporations with 143 homebuilding facilities located in more than 20 states. The industry produced over 105,000 homes in 2021 alone.

- Traditionally, building standards for manufactured housing have been created and enforced exclusively by HUD. HUD’s mandate to regulate manufactured housing derives from the National Manufactured Housing Construction and Safety Standards Act, 42 U.S.C. § 5401 et seq. (the “Manufactured Housing Act”), an express purpose of which is “to facilitate the availability of affordable manufactured homes and to increase homeownership for all Americans.” 42 U.S.C. § 5401(b)(2).

- Pursuant to its statutory authority under the Manufactured Housing Act, HUD has promulgated construction and safety standards for manufactured homes. See 24 C.F.R. Part 3280 (the “HUD Code”). In the Manufactured Housing Act, Congress instructed that the HUD Code must “ensure that the public interest in, and need for, affordable manufactured housing is duly considered.” 42 U.S.C. § 5401(b)(8).

- HUD enforces the HUD Code through a comprehensive and exhaustive set of rules and regulations. See 24 C.F.R. Part 3282. To take just one example, HUD regulations require each manufactured home design to be reviewed and approved by a third-party Design Approval Primary Inspection Agency (“DAPIA”). 24 C.F.R. § 3282.203. In addition, each manufactured home must be inspected by a separate Production Inspection Primary Inspection Agency (“IPIA”). 24 C.F.R. § 3282.204. Manufacturers pay DAPIAs and IPIAs directly for their inspection services, and those agencies certify compliance with the HUD Code. 24 C.F.R. § 3282.202. Only after the necessary approval from these primary inspection agencies may a home be certified as compliant with the HUD Code and sold to consumers. Manufacturers also pay HUD a fee for a HUD certification label, which all manufactured homes must display.

- Manufactured housing is the only form of housing regulated by a federal building code. Unlike site-built homes, which are subject to different state and local regulations, manufactured homes are all built to one uniform federal code, the HUD Code.

- The manufactured housing industry works collaboratively with HUD to comply with the HUD Code’s standards for home construction. The industry has always supported energy conservation efforts and other reasonable environmental protection initiatives and will continue to do so. In 2020, more than 30% of new manufactured homes met or exceeded Energy Star efficiency standards.[11]

- Indeed, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2020, the median size of a traditional site-built single-family home was 2,261 square feet, while the median size of a manufactured home was only 1,338 square feet. The significant difference is size correlates with a significant reduction in energy usage. As explained by the U.S. Energy Information Administration, “most energy end-uses are correlated with the size of the home. As square footage increases, the burden on heating and cooling equipment rises, lighting requirements increase, and the likelihood that the household uses more than one refrigerator increases.”

- Further, the manufactured home industry is a pioneer in the development of construction processes that value and prioritize energy efficiency. Manufacturers are constantly developing new initiatives and technologies, such as comprehensive recycling programs, to reduce waste. Through the controlled environment of the factory-built process, manufacturers are able to use exact dimensions and measurements for most building materials. Today’s modern manufacturing plants are so efficient that nearly everything is reused or recycled, including cardboard, plastic, carpet padding, vinyl siding, scrap wood and much more. See Final Rule Admin. Record, EERE-2009-BT-BC-0021-1592.

- According to a recent Freddie Mac study, “[e]nergy efficiency built into the homes themselves and an eco-friendly manufacturing process mean manufactured homes far surpass sitebuilt in terms of their environmental footprint. The factory home building process produces a fraction of the waste compared to a site-built home.”[12]

II. DOE’s Energy Standards Rulemaking Process and the Final Rule

A. In 2007, Congress Directs DOE to Promulgate Energy Standards for Manufactured Housing

4o. In 2007, Congress passed the EISA, which provides that “[n]ot later than 4 years after December 19, 2007, the [DOE] Secretary shall by regulation establish standards for energy efficiency in manufactured housing.” 42 U.S.C. § 17071(a)(1).

41. The EISA imposes two significant requirements for DOE’s rulemaking.

42. First, the EISA directs DOE to consult with HUD in preparing the standards. See 42 U.S.C. § 17071(a)(2)(B) (providing that the energy standards “shall be established after . . . consultation with the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, who may seek further counsel from the Manufactured Housing Consensus Committee”).

- Second, the EISA directs that, in promulgating the energy standards, DOE must ensure that the standards are “cost-effective,” taking into account the economic impact on “the purchase price of manufactured housing and on total life-cycle construction and operating costs.” 42 U.S.C. § 17071(b)(1) (emphasis added). More specifically, the statute provides that the standards “shall be based on the most recent version of the International Energy Conservation Code (including supplements), except in cases in which the Secretary finds that the code is not cost-effective, or a more stringent standard would be more cost-effective, based on the impact of the code on the purchase price of manufactured housing and on total life-cycle construction and operating costs.”

B. Between 2010 and 2016, DOE Prepares and Then Withdraws a Set of Proposed Energy Standards for Manufactured Housing

44. In February 2010, DOE initiated the process of developing energy standards for manufactured housing with an advance notice of proposed rulemaking in which it solicited information and data from stakeholders. See 81 Fed. Reg. at 39,762.

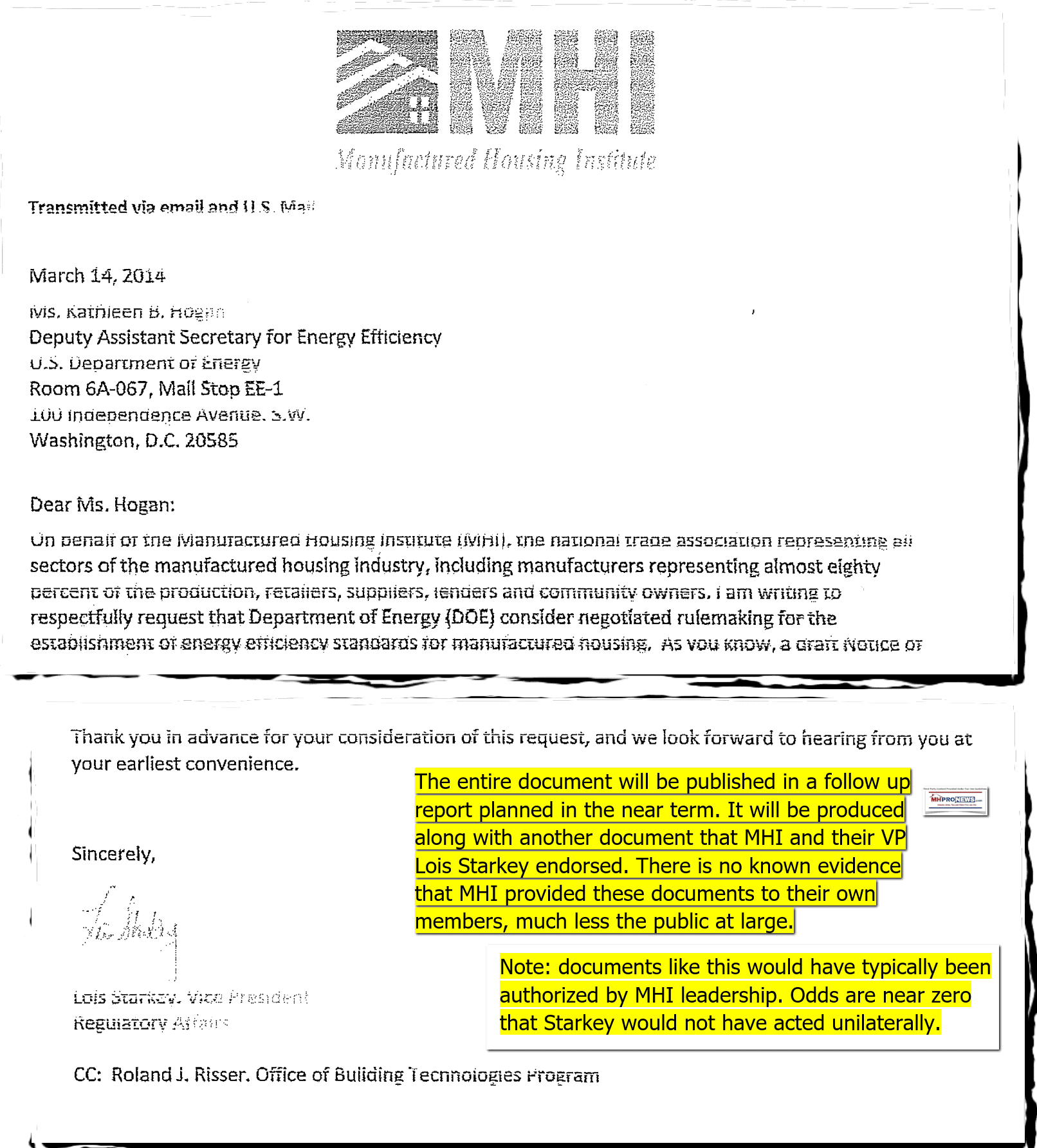

45. DOE ultimately decided that the development of its energy standards for manufactured housing would benefit from a negotiated rulemaking process. In June 2014, DOE published a notice of intent to establish a manufactured housing (“MH”) working group to discuss and, if possible, reach consensus on a proposed set of energy standards. The MH working group was made up of representatives from interested stakeholders with a directive to consult, as appropriate, with a range of external experts on technical issues. The working group consisted of 22 members, including one member from the Appliance Standards and Rulemaking Federal Advisory Committee (“ASRAC”) and one DOE representative. There was no HUD representative in the working group.

- The MH working group met in person during four sets of public meetings held in 2014. See 81 Fed. Reg. at 39,765. In October 2014, the working group reached consensus on a proposed set of energy standards for manufactured housing and assembled its recommendations for DOE into a term sheet that was presented to ASRAC. ASRAC approved the term sheet during an open meeting in December 2014 and sent it to DOE to develop a proposed rule. See 81 Fed. Reg. at 39,765.

- In June 2016, DOE published a notice of proposed rulemaking in which it proposed a set of energy standards for manufactured housing. 81 Fed. Reg. 39,756 (the “2016 Proposed Rule”). Importantly, the 2016 Proposed Rule was “based on the 2015 edition of the International Energy Conservation Code” (“2015 IECC”). Id. Likewise, the cost estimates that the MH working group considered in preparing its recommendations were also based on the 2015 IECC. See, e.g., Final Rule Admin. Record, EERE-2009-BT-BC-0021-0090.

- In conjunction with the 2016 Proposed Rule, DOE published a companion notice of proposed rulemaking in which it set out procedures for testing manufacturer compliance with the proposed energy standards. As stated by DOE in that proposed “test procedures” rulemaking:

Test procedures are necessary to provide for accurate, comprehensive information about energy characteristics of manufactured homes and provide for the subsequent enforcement of the standards. See 42 U.S.C. 7254, 17071. The test procedure [notice of proposed rulemaking] proposes applicable test methods to support the energy conservation standards for the proposed thermal envelope requirements, air leakage requirements, and fan efficacy requirements. The test procedure would therefore dictate the basis on which a manufactured home’s performance is represented and how compliance with the proposed energy conservation standards, if adopted, would be determined.

81 Fed. Reg. at 78,734 (emphasis added). In sum, “[t]he proposed test procedures are used as the basis for manufacturers to show compliance with the energy conservation standards, once finalized and compliance is required.” 81 Fed. Reg. at 78,735 (emphasis added).

- In proposing test procedures to accompany its energy standards, DOE adopted existing and successful, industry-accepted testing methods. As it explained in the proposed rulemaking, “by aligning with industry-accepted test methods, it is expected that the DOE test procedures will be less burdensome than if DOE were to establish new test procedures for manufactured housing manufacturers.” 81 Fed. Reg. at 78,737. Toward that end, the proposed test procedures would have expressly allowed manufacturers to rely on energy efficiency “values currently being determined by component manufacturers and that are provided as part of the component specification sheets.”

- The 2016 Proposed Rule did not clear the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs’ (“OIRA”) review process under Executive Order 12866 and was withdrawn in January

- See 83 Fed. Reg. at 38,074–75. In withdrawing the 2016 Proposed Rule, DOE cited Executive Order 13771 from the Administration of President Donald J. Trump, which required DOE “to manage the costs associated with the imposition of expenditures required to comply with Federal regulations.” See 83 Fed. Reg. at 38,075. Executive Order 13771 stated, for example, that “[u]nless prohibited by law, whenever an executive department or agency (agency) publicly proposes for notice and comment or otherwise promulgates a new regulation, it shall identify at least two existing regulations to be repealed.” 82 Fed. Reg. at 9,339.

C. In 2017, the Sierra Club Files Suit to Compel DOE to Complete Its Rulemaking

51. In the wake of DOE withdrawing the 2016 Proposed Rule, in December 2017, the Sierra Club filed suit in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia to compel DOE to complete its energy standards rulemaking. See Sierra Club v. Rick Perry, Civil Action No. 1:17-cv-02700-EGS, Dkt. No. 1 (D.D.C. Dec. 18, 2017). In that suit, the Sierra Club alleged that DOE had failed to comply with its statutory mandate to promulgate energy standards for manufactured housing. Id. It demanded that DOE complete a final rule establishing those standards as required by the EISA. Id.

- In November 2019, DOE and the Sierra Club entered into a stipulated consent decree in which DOE agreed to publish a final rule establishing energy standards for manufactured housing no later than February 14, 2022. Sierra Club, Dkt. No. 42. By agreement of those parties, that deadline was later extended until May 16, 2022. Sierra Club, Dkt. No. 45.

D. In 2022, DOE Prepares a New Set of Energy Standards and Publishes the Final Rule

53. Faced with the Sierra Club litigation, in August 2018, DOE published a new notice of data availability and request for information in which it solicited public input on some of the data it planned to use to develop a new set of proposed energy standards for manufactured housing. See 83 Fed. Reg. at 38,073. And in August 2021, DOE published a supplemental notice of proposed rulemaking in which it set out those proposed standards (the “2021 Proposed Rule”). See 86 Fed. Reg. at 47,744.

- Unlike the 2016 Proposed Rule, which had proposed energy standards that were based on the 2015 IECC, the 2021 Proposed Rule proposed standards that were based on a more recent version of the IECC, the 2021 edition (“2021 IECC”). See 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,738. Despite material differences between the 2021 and 2015 versions of the IECC, DOE did not reconvene the MH working group to assess those differences at any point during its rulemaking. In fact, following its withdrawal of the 2016 Proposed Rule, DOE has not reconvened the MH working group at all.

- Unlike manufactured housing that is governed by HUD or State Administrative Agencies to which HUD has delegated authority, site-built residential construction is governed by local code authorities that adopt various versions of model codes. Only four states have adopted the 2021 IECC’s standards for construction of site-built homes. The vast majority of local code authorities have adopted and enforce the 2012 or 2015 IECC’s standards for construction of sitebuilt homes. No stakeholders from the manufactured housing industry were involved in drafting the 2021 IECC.

- After a public comment period, DOE promulgated a final set of energy standards for manufactured housing in the Final Rule. The Final Rule was published on May 31, 2022, with an effective date of August 1, 2022. The Final Rule requires that all construction of new manufactured homes must comply with the new energy standards beginning on May 31, 2023— only one year after the date the standards were published and less than a year after the Final Rule’s effective date. See 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,728.

- The Final Rule promulgated a detailed set of energy conservation regulations governing the construction of manufactured homes, to be codified in 10 C.F.R. Part 460. It establishes two “tiers” of energy standards that are both based on the 2021 IECC. As stated in the Final Rule, “DOE is finalizing a tiered standard whereby single-section manufactured homes (“Tier 1” manufactured homes) would be subject to different building thermal envelope requirements (subpart B of 10 CFR part 460) than all other manufactured homes (“Tier 2” manufactured homes). Both tiers are based on the 2021 IECC in that both tiers have requirements for the building thermal envelope, duct and air sealing, installation of insulation, HVAC specifications, service hot water systems, mechanical ventilation fan efficacy, and heating and cooling equipment sizing provisions consistent with the 2021 IECC.” 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,741.

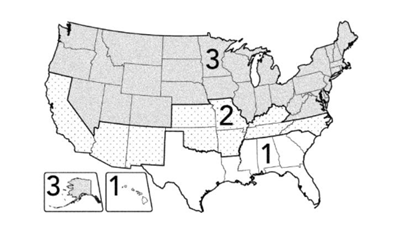

- The Final Rule applies these two “tiers” to each of the three “climate zones” for manufactured housing as established by HUD—thereby resulting in standards for each climate zone by each tier. The climate zones in the Final Rule are depicted below:

- In the Final Rule, DOE projects that the Tier 1 standards (e., the standards for single-section homes) will result in an average incremental purchase price increase of approximately $700 per home. And DOE projects that the Tier 2 standards (i.e., the standards for multi-section homes) will result in an average incremental purchase price increase of approximately $4,100 to $4,500 per home. 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,741.

- The Final Rule also purports to calculate the life-cycle costs (“LCC”) that will result from the energy standards, taking into account projected costs during the construction phase and projected savings in consumers’ operation of their homes. “The LCC savings accounts for the energy cost savings and purchase costs (including down payment, mortgage and taxes based on incremental purchase price) over the entire analysis period discounted to a present value.” 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,742. As for the effect the purchase price increases will have on the housing market,

DOE estimates that the Final Rule “would result in a loss in demand and availability of about 31,975 homes (single section and multi-section combined) for the tiered standard using a price elasticity of demand of -0.48 for the 30-year analysis period (2023-2052).” 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,746.

III. The Final Rule Is Unlawful in Several Respects

A. DOE Failed to Analyze Test Procedures and Compliance and Enforcement Costs for the New Energy Standards

61. In its rush to meet the Sierra Club deadline, DOE issued a Final Rule that was procedurally and substantively legally defective in a number of ways. The first error in DOE’s rulemaking was its deliberate choice to ignore test procedures and compliance and enforcement costs. DOE readily concedes that it “is not addressing a test procedure, or compliance and enforcement provisions for energy conservation standards for manufactured housing.” 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,743. In other words, while the Final Rule promulgates energy standards for manufactured housing, DOE has not established any test procedures for determining compliance with those standards, nor has DOE conceptualized an enforcement scheme for the standards.

62. In contrast, when it developed the 2016 Proposed Rule, DOE acknowledged and recognized that test procedures are a “necessary” part of its energy standards rulemaking. In DOE’s words at that time, test procedures “dictate the basis on which a manufactured home’s performance is represented and how compliance with the proposed energy conservation standards, if adopted, would be determined.” 81 Fed. Reg. at 78,734. For the 2016 Proposed Rule, DOE contemplated that “[t]he proposed test procedures [would be] used as the basis for manufacturers to show compliance with the energy conservation standards, once finalized and compliance is required.” at 78,735. Yet, in the Final Rule, DOE demands compliance with its overhauled set of energy standards by May 31, 2023, without even having begun rulemaking to develop test procedures for determining compliance with those standards—assuming it intends to do so at all.

63. DOE states in the Final Rule that it “continues to consult with HUD about pathways to address testing, compliance and enforcement for these standards in a manner that may leverage the current HUD inspection and enforcement process so that such testing, compliance and enforcement procedures are not overly burdensome or duplicative for manufacturers, and are well understood by manufacturers and consumers alike.” 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,743. But that alleged perfunctory consultation has produced nothing official. Absent formal test procedures or compliance and enforcement standards, DOE has no way to know how burdensome or duplicative for manufacturers the Final Rule’s energy standards will actually be.

64. Moreover, in November 2022, the MHCC convened to address DOE’s Final Rule as it relates to possible revisions to the HUD Code. Rather than recommending that HUD enforce

DOE’s Final Rule, the MHCC rejected the DOE’s Final Rule and recommended that HUD adopt different energy efficiency standards into the HUD Code. See supra at ¶ 10.

- Indeed, with regard to the costs its energy standards will impose on manufacturers,

DOE flatly concedes that it “has also not included any potential associated costs of testing, compliance or enforcement at this time.” 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,758; see also 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,790.

In fact, in the Final Rule’s cost analysis, DOE presents “the average purchase price increase of a manufactured home as a result of the energy conservation standards,” while admitting that its calculation of that projected price increase “does not include any potential testing or compliance costs.” 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,730 (emphasis added).

- With no guidance from DOE about testing procedures or compliance and enforcement costs, the industry is arbitrarily and capriciously burdened with the actual, unidentified costs caused by the Final Rule. The industry has every reason to expect that testing procedures—assuming DOE at some point develops them—will be costly.

- As just one example, the industry initially estimated that testing for duct system compliance under the new energy standards could cost more than $600 per home for Tier 1 homes and more than $1,000 per home for Tier 2 homes. A more recent estimate from a leading manufactured housing duct-testing expert found that in-field duct testing could cost approximately $1,500 per home for both Tier 1 and Tier 2 homes given that manufactured housing is predominately located in rural areas which would entail extensive travel requirements for in-field examiners. This estimate assumes that the homes would pass such in-field duct testing on the first attempt. Any failed test would further increase testing and remediation costs. And this duct testing expert also opined that there is a severe shortage of qualified entities capable of performing such in-field duct testing on manufactured homes.

- DOE explicitly acknowledges that it failed to factor testing costs into its assessment of the Final Rule’s impact to the purchase price and life-cycle costs of manufactured homes. Yet, if DOE had attempted to account for the cost of testing procedures related solely to the new duct system standard—which is only one of the many new energy standards the Final Rule imposes— then DOE’s 10-year LCC assessment would fail. DOE estimated that over a 10-year period, customers would save a total of $720 for Tier 1 homes and a total of $743 for Tier 2 homes— which essentially calculates the total 10-year energy savings minus the total 10-year cost increases for implementing the energy efficiency measures. See 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,793. Assuming duct testing costs $1,500 on average per home, then manufactured housing consumers will lose money over 10 years based on the DOE’s Final Rule. Again, this analysis relates only to duct system testing and not the total cost of testing procedures for all of the Final Rule’s energy standards.

- DOE specifically stated that its cost-effective analysis requires that the Final Rule’s standards create savings for consumers after 10 years. See 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,786 (“DOE continues to rely on the 10-year time period as a reasonable representation of the ownership period of the first homebuyer for the overall manufactured housing market . . . .”). Yet, when accounting for only some of the costs that DOE willfully ignored, consumers will not see any savings within the first 10 years after their purchase of a manufactured home.

- During rulemaking, DOE was fully aware of the significant costs that testing procedures are likely to impose on manufacturers, but nonetheless elected to ignore these additional costs. Plaintiff MHI raised this issue with DOE during the public comment period, noting in a letter that “the required testing for the duct leakage limitation is also unknown at this time and therefore has not been included in the DOE cost analysis.” See Final Rule Admin. Record,

EERE-2009-BT-BC-0021-1592. The unknown burden on the industry associated with DOE’s failure to develop testing procedures and consider their costs was explained in this same letter:

For multi-sectional units where ductwork is installed on-site, the rule does not establish enforcement procedures for testing. More specifically, what qualifications are required for those performing the testing? Can installers certify their own work? What training is required for installer personnel performing this work? How are the test results documented? Is the installer responsible for any remedial work that may be required after the testing is performed? These questions must be answered in order to determine the additional costs which may be attached to such.

Id.

- As to compliance and enforcement, Plaintiffs’ members similarly have no way to know the costs that DOE’s enforcement and compliance mechanisms will impose without knowing what those mechanisms will be. For reference, HUD’s inspection agencies and HUD labeling requirements cost manufacturers approximately $180 to $360 per home. If DOE develops its own enforcement mechanism, manufacturers would presumably have to pay additional fees to DOE’s inspection agencies on top of the HUD-specific inspection fees. Those DOE inspection fees will only further increase the purchase price of manufactured housing. Again, because the Final Rule fails to develop or identify any compliance and enforcement mechanisms, DOE did not factor the costs of such mechanisms into the Final Rule’s assessment of purchase price or life-cycle cost

increases to manufactured housing.

B. In Requiring Manufacturers to Comply with the New Energy Standards by May 31, 2023, DOE Failed to Account for Current Economic Conditions and Supply Chain Realities.

72. The defects in DOE’s rulemaking do not end with its failure to consider testing procedures and compliance and enforcement costs. The Final Rule also fails to account for actual market conditions.

73. To determine 2023 materials cost for the newly required energy efficiency measures, the Final Rule arbitrarily and capriciously took outdated 2014 cost estimates and applied a hypothetical nominal materials cost increase of 2.3% annually from 2014 to 2023. However, this assumption fails to comport with actual cost increases caused by the Covid-19 pandemic as well as other macroeconomic factors. As was well-known at the time DOE published the Final Rule in

May 2022, the cost of construction materials has actually increased by 6.5% annually between 2014 and 2021—driven mostly by materials cost increases of 35.1% from 2020 to 2021. Another economic study concluded that construction materials increased on average 41% from March 2020 to March 2022. The manufactured housing construction costs may be even higher.

- Additionally, in assessing financing for manufactured homes—which is a component of the DOE’s LCC model—DOE assumed that real estate mortgage loans would have a 5% interest rate. The current 30-year fixed mortgage rate is now 6.3%, meaning that DOE woefully underestimated the borrowing cost to finance these newly required energy efficiency measures.

- Economists conclude that if DOE’s 10-year LCC model appropriately considered the actual annual cost increase for construction materials since 2014 and considered the actual cost of borrowing, DOE’s own 10-year LCC model would fail completely for Tier 2 manufactured homes. This analysis accounts for the increased energy savings that may also result from inflation. Fixing only these two inputs to reflect actual materials cost increases and actual interest rates, based on DOE’s own 10-year LCC model for Tier 2 homes, the average 10-year LCC is negative— meaning that the average purchaser of a Tier 2 home will lose money over a 10-year period.

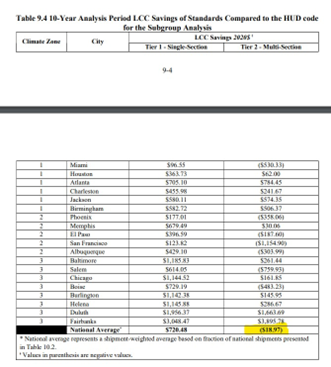

- In terms of geographic distribution, approximately 60% of Tier 2 shipments will have a negative 10-year LCC. Of the 19 “representative” cities chosen by the DOE to analyze in the Final Rule, nine cities will have a negative 10-year LCC for Tier 2 homes.

- Again, DOE specifically stated that the legitimacy of its cost-effective analysis depends on the Final Rule’s standards creating savings for consumers after 10 years. See 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,786. But when appropriate, realistic economic assumptions are made, the vast majority of Tier 2 manufactured home consumers will actually lose money in this time period as a result of the Final Rule.

- Moreover, DOE also arbitrarily assumed that existing supply chains could support the materials necessary for manufacturers to comply with the Final Rule by May 31, 2023. In the Final Rule, DOE undertook no meaningful analysis to determine whether supply chains could in fact support the increased demand for the materials needed to satisfy the Final Rule’s standards in

such a short time frame.

- As one commentator to the Final Rule stated during the rulemaking period, the new standards would “require manufactured homes to have significantly more insulation, which would cause the demand for fiberglass insulation to overwhelm a market that is already under substantial stress from the current insulation shortage, which is projected to continue for a few more years.” See 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,774. As a result, the effect of the proposed rule would significantly limit the number of new homes starts in America while increasing national building costs.

- To illustrate, one 2022 study found a 40-50 week lead time for roofing insulation, which represents a 667% increase over the past two years. The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’ Producer Price Index (PPI) for insulation materials establishes that insulation costs have increased by over 35% since 2020.

- The industry fully expects that production ramp-ups from insulation supply manufacturers will lag behind the Final Rule’s May 31, 2023 compliance date. Thus, in the short to medium term, the cost of insulation will almost certainly increase substantially above DOE’s projected materials cost, and new home starts in America may be severely limited by the current insulation shortage until supply chain issues are resolved.

- DOE’s response to these serious and specific concerns in the Final Rule was severely underwhelming. DOE stated simply that “the performance path, i.e., Uo[[13]] method, gives manufacturers the flexibility in using any combination of energy efficiency measures as long as the minimum Uo is met. Manufacturers do not need to meet both the prescriptive and the performance method; rather they have the option to only meet one. As such, manufacturers can continue to use current insulation types and techniques to meet the energy conservation standards. DOE is not restricting the type of insulation being used, as long as the standards (either prescriptive or performance) are met.” 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,774. But the “performance path” will still require sourcing additional insulation. If fiberglass insulation is not available, manufacturers may be forced to substitute spray foam insulation for parts of the production process, which will further increase costs and will reduce the total number of homes that can be produced per day.

- DOE also failed to assess whether the “performance path” described above is actually achievable for the manufactured housing industry using existing construction methods. It may not be for many Tier 2 homes especially in climate Zone 3, which covers the northern part of the United States. At no point in the Final Rule did DOE meaningfully grapple with the severity of the market impact from supply shortages.

- For example, manufacturers likely cannot meet Tier 2 requirements using 2×4 wall constructions. Rather, for Tier 2 homes, manufacturers must change to 2×6 wall constructions. See, e.g., Final Rule Admin. Record, EERE-2009-BT-BC-0021-1592 (estimating a “cost increase of over $7,000 for a multi-section home located in climate zone 3 – without including the costs of energy testing or compliance”—almost double the $4,111 incremental cost increase estimated by DOE).

- As yet another example, the Final Rule’s approach to equipment sizing is flawed. Absent the Final Rule, a Zone 2 home can be placed in Zone 1 because Zone 2 is more restrictive than Zone 1. However, the Final Rule adopts Manual S, and under Manual S, a Zone 2 home cannot be placed in Zone 1 because the equipment sized for Zone 2 would be oversized for Zone 1. In this regard, the Final Rule severely restricts current sales practices, especially for retailers located near the zone boundaries. See Final Rule Admin. Record, EERE-2009-BT-BC-0021-1592.

- The Final Rule also fails to account for increased transportation costs. Additional insulation and framing requirements may increase the weight of manufactured homes, requiring an additional axle, which may cost at least $400 for Tier 2 homes. Even without these considerations, transportation costs have generally increased dramatically during the Covid-19 pandemic with increased fuel and labor costs due to shortages. DOE did not account for the economic realities imposed by these additional costs despite the DOE being required to do so as part of its creation and implementation of the Final Rule.

C. Many Consumers will be Priced Out of the Manufactured Housing Market.

87. Beyond the fact that many consumers will be forced to purchase energy efficiency measures that will not pay for themselves even over a 10-year period, these unaccounted-for costs will mean that thousands of consumers are simply priced out of the manufactured home market altogether. As stated by Plaintiff MHI in its November 23, 2021 letter to DOE, “the proposed energy standards ignore the large number of homebuyers that will no longer be able to buy a manufactured home, because they no longer qualify for an FHA, GSE, or non-agency mortgage loan, due to the impact of increased mortgage payments on debt-to-income ratios.” See Final Rule Admin. Record, EERE-2009-BT-BC-0021-1592.

88. To assess how many customers would be priced out of home ownership given the estimated increased purchase price associated with the newly mandated energy efficiency measures, DOE relied on a 2008 study that cited a -0.48 price elasticity of demand for manufactured housing. Price elasticity of demand measures how many customers will no longer be willing to purchase a product as the product’s price increase. DOE also performed a sensitivity analysis relying upon another study which suggested a -2.4 price elasticity of demand. Another 2021 study found a -0.8 price elasticity of demand. Based on purchase price increases, economists estimate that the Final Rule could lead to between 1,703 and 5,101 fewer manufactured home sales each year over the next ten years (for a total of between 17,030 and 51,010 fewer homes).

89. Consumers cannot reap any benefits of energy standards if they are priced out of home ownership to begin with. DOE’s Final Rule therefore only exacerbates an already dire affordable housing crisis facing many millions of American families. And in that regard, the Final

Rule cuts against the current Administration’s affordable housing initiative to “boost the supply of manufactured housing.”[14]

D. The Final Rule Will Disproportionally Impact Minority and At-Risk Purchasers.

90. DOE acknowledges that most manufactured home buyers finance their purchases through personal property loans that resemble vehicle financing rather than traditional mortgage financing. See 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,742. In the Final Rule, DOE noted that personal property loans typically carry significantly higher interest rates than traditional mortgage loans. And DOE recognized that, for manufactured home buyers who do not own the land on which they reside, personal property financing is usually the only type of financing available. See id. at 32,788.

91. Data from the CFPB, which DOE relied upon extensively throughout the Final Rule, indicates that manufactured home buyers from underrepresented groups are disproportionately likely to obtain personal property loans rather than traditional mortgage loans. See CFPB, Manufactured Housing Finance: New Insights from the Home Mortgage

Disclosure Act Data (May 2021), at 5 (noting that “Hispanic, Black and African American, American Indian and Alaska Native, and elderly borrowers are more likely than other consumers to take out chattel loans,” and that “Black and African American borrowers are the only racial group that are underrepresented in manufactured housing lending overall compared to site-built, but overrepresented in chattel lending compared to site-built”).

- Given the prevalence of personal property loans among underrepresented groups, one might expect that DOE would have taken special care to ensure that manufactured home buyers who finance their purchases with personal property loans will not be negatively affected by its new energy standards. But DOE’s own data reveals quite the opposite—it shows that personal property loan borrowers will be especially negatively affected. The Final Rule thus makes affordable housing even more difficult for people in these underrepresented groups.

- In supporting technical documentation released in conjunction with the Final Rule, DOE openly admitted that, although it projects the “national average” manufactured home buyer to recoup the higher purchasing and operating costs associated with the new energy standards within the first 10 years of homeownership, DOE fully expects that consumers who purchase Tier

2 manufactured homes with personal property financing will on average lose money in the first 10 years as a result of the new standards.

Final Rule Admin. Record, EERE-2009-BT-BC-0021-1999, at 9-4 & 9-5.

- Thus, not only will DOE’s Final Rule not advance the goal of improving racial equity in homeownership—it will actively work against it by disproportionately harming a large sector of the manufactured housing market in which minority groups are overrepresented.

E. The Final Rule’s One-Year Compliance Period Is Unreasonable.

95. Strikingly, when DOE substantially overhauls energy standards for household appliances, it generally provides a five-year compliance period. Notwithstanding the fact that the process for manufacturing homes is far more complex than a single appliance manufacturing processes, in the Final Rule, DOE capriciously shortened and compressed the typical compliance deadline to one year (and less than one year from the Final Rule’s effective date). Every home design currently being utilized by the manufactured housing industry—of which there are thousands—would need to be redesigned and reapproved during this brief time period.

96. Indeed, despite never regulating manufactured housing before, DOE’s Final Rule is based on standards from the 2021 IECC. In doing so, DOE bypassed incremental upgrades to energy efficiency measures from the 2015 and 2018 versions of the IECC and disregarded the existing regulations that HUD has established over decades. The Final Rule therefore condensed almost a decade of incremental energy efficiency upgrades into the Final Rule and demanded that the manufactured housing industry comply with such expansive requirements within 12 short months.

97. DOE ignored these concerns as raised by Plaintiff MHI in its February 28, 2022 comment letter:

In the draft EIS, the DOE proposes a one-year implementation period. However, when the DOE makes changes to appliance standards there is at least a five-year compliance period. For example, on January 6, 2017, the DOE published a final rule to establish energy conservation standards for residential central air conditioners and heat pumps with a compliance date of January 1, 2023 (Docket Number EERE-2014-BT-STD-0048-0200). Additionally, on April 16, 2010, the DOE published amendments to the existing energy conservation standards for residential water heaters, gas-fired direct heating equipment, and gas-fired pool heaters. While the effective date of the rule was June 15, 2010, compliance with the standards was not required until April 16, 2015 (Docket Number EE–2006–BT– STD–0129).

Final Rule Admin. Record EERE-2009-BT-BC-0021-1990.

- DOE also ignored comments from HUD as expressed through MHCC on this topic, which “commented that major changes to the manufacturer’s process, facilities, home designs, and supply chains would be required to comply with the DOE standards and a more realistic time frame for implementation would be a minimum of 5 years.” 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,759. Similarly, Plaintiff TMHA “requested that any effective date consider having backlogs and supply-chains to have returned to normal.”

- In the Final Rule, DOE did not consider whether manufacturers could actually meet the May 31, 2023 compliance deadline for the new energy standards. Instead, DOE arbitrarily assumed, without any support, that because manufacturers have had to comply with HUD’s energy requirements, they can also comply with the Final Rule’s dictates within a year. See 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,759. DOE made that uninformed determination without considering the compliance runway provided by such other energy standards applicable to the manufactured housing industry.

- The arbitrariness of the May 31, 2023 compliance date is further underscored by the fact that DOE has demanded compliance with the new energy standards on an aggressive timetable before it has adopted or even developed any testing procedures or compliance and enforcement mechanisms.

F. DOE Failed to Consult with HUD About the New Energy Standards

101. In developing the Final Rule, DOE also failed to meaningfully consult with HUD as is required by the EISA.

102. Years ago, when it prepared a different set of proposed (and never-adopted) energy standards culminating in the 2016 Proposed Rule, DOE appears to have interacted with HUD to at least some minimal extent. Leading up to the 2016 Proposed Rule, it appears the following events may have taken place: (a) DOE purportedly provided a draft notice of proposed rulemaking and technical support document for HUD to review; (b) HUD attended the MH working group meetings (even though it was not a member of the MH working group); (c) DOE met with HUD’s

MHCC; (d) DOE’s and HUD’s general counsels spoke by phone several times; and (e) HUD participated in the interagency review of the 2016 Proposed Rule coordinated by OIRA. See, e.g., Final Rule Admin. Record EERE-2009-BT-BC-0021-0146, at 11.

- However, even if DOE’s efforts to consult with HUD regarding the 2016 Proposed

Rule were sufficient to satisfy the EISA’s consultation requirement—and they were not—DOE undertook no such efforts to consult with HUD in promulgating the Final Rule, which materially differs from the 2016 Proposed Rule. See, e.g., 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,763.

- With regard to the energy standards set forth in the Final Rule, DOE never met with the MH working group. In technical documentation it prepared in conjunction with the new energy standards, DOE acknowledged that the Final Rule is based on the 2021 IECC, not the 2015 IECC.

And, DOE concedes that “the 2015 edition of the IECC was the latest edition of the IECC at the time of the MH working group meetings.” Final Rule Admin. Record EERE-2009-BT-BC-00210590, at 3-1.

- While the Final Rule cites DOE meetings with HUD and the MHCC, those citations generally refer to meetings related to the 2016 Proposed Rule, see, e.g., 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,737, not the materially different Final Rule published six years later. DOE cannot reasonably claim that

DOE complied with the EISA’s consultation requirement when DOE’s cited consultation relates to a completely different set of proposed energy standards. At best, the Final Rule cites in passing that some representatives from DOE “attended” a MHCC meeting in June 2021. Sitting at one meeting does not constitute a consultation about the substance of the energy standards proposed by DOE.

- Indeed, as to the Final Rule, the MHCC commented that “they believe the energy efficiency requirements from the 2021 IECC, as currently proposed, are not the appropriate resource to be used in updating manufactured housing energy requirements, as the 2021 IECC was not developed or intended for these homes.” 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,748 (emphasis added).

- The MHCC met again in October and November 2022 after DOE promulgated the

Final Rule, and the MHCC flatly rejected the DOE’s Final Rule. See supra at ¶ 10.

- The Final Rule indicates that HUD voiced concerns about the 2016 Proposed Rule. See, e.g., 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,729. But there is no record of DOE consulting with HUD to actually develop the Final Rule. Rather, DOE pays lip service to HUD, stating: “DOE remains cognizant of the HUD Code, as well as HUD’s Congressional charge to protect the quality, durability, safety, affordability, and availability of manufactured homes.” 87 Fed. Reg. at 32,736. Remaining “cognizant” of the HUD Code is a far cry from actually consulting with HUD to obtain HUD’s expertise in manufactured housing, especially considering that the MHCC adamantly opposes adoption of the Final Rule.

- In cursory fashion and with no information as to the substance of any such meeting,

DOE states that it “consulted HUD in the development of the August 2021 SNOPR, the October 2021 NODA and this final rule.” 87 Fed. Reg at 32,756. No additional information is provided and the administrative record is devoid of any evidence of those cited “consultations.” The Final Rule’s administrative record contains no documentation memorializing any meeting between HUD and DOE about the Final Rule.

- Similarly, there is no indication in the Final Rule that HUD participated in the interagency review of the 2021 Proposed Rule coordinated by OIRA. Indeed, six months after receiving FOIA requests on this specific subject from MHI, DOE has provided no responsive documentation.

- The MHCC did provide public comments to DOE regarding the Final Rule, but offering public comments does not equate to consultation. Public comment is always available for agency rulemaking, so the EISA’s consultation requirement must mean something more.

CLAIMS FOR DECLARATORY AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF

Count I – the Final Rule Violates the APA and the EISA (Contrary to Law)

- Plaintiffs incorporate the foregoing allegations by reference.

- The APA authorizes courts to hold unlawful and set aside agency action, findings, and conclusions that are “in excess of statutory jurisdiction, authority or limitations, or short of statutory right.” 5 U.S.C. § 706(2)(C). Additionally, agency action must be set aside where it is

“without observance of procedure required by law.” Id. § 706(2)(D).

- In promulgating the Final Rule, DOE acted contrary to the EISA in several ways, including in the following respects:

- First, by failing to consider any costs related to testing procedures or compliance and enforcement, DOE failed to satisfy its statutory obligation to consider the impact of the Final Rule’s energy standards on the “purchase price of manufactured housing and on total life-cycle construction and operating costs.” 42 U.S.C. § 17071(b)(1). “There can be no ‘hard look’ at costs and benefits unless all costs are disclosed.” Sierra Club v. Sigler, 695 F.2d 957, 979 (5th Cir.

1983); Gas Appliance Mfrs. Ass’n, Inc. v. Dep’t of Energy, 998 F.2d 1041, 1047–49 (D.C. Cir. 1993) (holding that DOE had entirely failed to consider the cost to manufacturers of installing new devices such as flue dampers necessary to meet the new standards’ requirements, and that those costs “must be included if the cost-benefit analysis is to be a coherent marginal analysis”).

- Second, by woefully understating the actual costs necessary to comply with the

Final Rule due to current economic conditions, DOE failed to satisfy its statutory obligation to consider the impact of the Final Rule’s energy standards on the “purchase price of manufactured housing and on total life-cycle construction and operating costs.” 42 U.S.C. § 17071(b)(1). Cf. Gas Appliance Mfrs. Ass’n, Inc. v. Sec’y of Energy, 722 F. Supp. 792, 795 (D.D.C. 1989) (“Increased energy efficiency must be weighed against potential increases in overall dollar costs arising from new standards under some articulated formula.”).

- Third, the Final Rule violates EISA because DOE failed to consult meaningfully with HUD. See Campanale & Sons, Inc. v. Evans, 311 F.3d 109, 116–21 (1st Cir. 2002)

(“[C]onsultation, within the parameters of the Atlantic Coastal Act, must mean something more than general participation in the public comment process on environmental impact statements, otherwise the consultation requirement would be rendered nugatory.”).

- Plaintiffs’ members will suffer irreparable harm if the Final Rule is not set aside. Despite the fact that the Final Rule is invalid, Plaintiffs’ members will be forced to redesign all of their homes and retool all of their factories in an effort to comply with the Final Rule. Yet, Plaintiffs’ members will have no way to ascertain compliance in the absence of testing procedures and compliance and enforcement provisions. In addition, a true cost assessment of the purchase price of homes and the life cycle of construction costs—as informed by actual consultation with

HUD—may result in a substantially different set of energy standards. Plaintiffs’ members would then be forced to redesign all of their homes and retool all of their factories again for compliance with purportedly valid energy standards.

- The public interest will in no way be harmed, and to the contrary, will be greatly served if the Final Rule is set aside. If a stay is not granted, the public interest will be harmed through the adverse effects on consumers that will result from a loss of affordable housing.

Maintaining the affordability of this sector is crucial to addressing the housing crisis sweeping the nation.[15] Yet the Final Rules threatens to do just the opposite. As it stands, tens of thousands of American families will be priced out of purchasing a manufactured home due to purchase price increases mandated by the Final Rule. For those who can still afford a manufactured home even after absorbing these purchase price increases, the Final Rule will result in a net cost to the vast majority of manufactured home purchasers within the first 10 years of their purchase. Plaintiffs, and the public at-large, support energy efficiency measures—but those energy efficiency measures must be balanced against their cost. Where, as here, the energy efficiency measures result in consumer harm, they should not be mandated by a governmental agency. That was the EISA’s

directive for which DOE failed to comply.

Count II – the Final Rule Violates the APA (Arbitrary and Capricious)

- Plaintiffs incorporate the foregoing allegations by reference.

- The APA authorizes courts to hold unlawful and set aside agency action, findings, and conclusions that are “arbitrary, capricious, and abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law.” 5 U.S.C. § 706(2)(A). To satisfy this standard, an agency must “examine the relevant data and articulate a satisfactory explanation for its action including a rational connection between the facts found and the choice made.” Motor Vehicle Mfrs. Ass’n of U.S., Inc. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 463 U.S. 29, 43 (1983) (quotation omitted). An agency acts arbitrarily and capriciously if it “has relied on factors which Congress has not intended it to consider, entirely failed to consider an important aspect of the problem, [or] offered an explanation for its decision that runs counter to the evidence before the agency[] or is so implausible that it could not be ascribed to a difference in view or the product of agency expertise.” Id. at 43.

- In promulgating the Final Rule, DOE acted arbitrarily and capriciously in the following ways:

- First, it was arbitrary and capricious for DOE to mandate compliance with the Final Rule before it establishes any testing procedures or a compliance and enforcement scheme related to the Final Rule. See Gas Appliance, 998 F.2d at 1045 (requiring “a discernible path to compliance” “where the agency must perform a direct balance of costs and benefits”). In the 2016 Proposed Rule, DOE stated that test procedures are “necessary” for any promulgated energy standards. But now in the Final Rule, DOE reverses course and demands industry compliance with energy standards that have no corresponding test procedures. That unexplained about-face in the agency’s approach to this important topic was arbitrary and capricious.

- In fact, with regard to other energy efficiency standards, DOE has refused to mandate compliance unless and until test-procedure rulemaking has been finalized. For example, on July 8, 2014, with regard to “Off Mode Standards for Central Air Conditioners and Central Air Conditioning Heat Pumps,” DOE issued a policy statement that: “In light of the lack of a final test method for measuring off mode electrical power consumption for CAC/HP, DOE will not assert civil penalty authority for violation of the off mode standard for CAC/HP specified at 10 C.F.R. § 430.32(c)(6) until 180 days following publication of a final rule establishing a test method for measuring off mode electrical power consumption for CAC/HP.” Based on DOE’s own policy guidance, it is arbitrary and capricious for DOE to demand a compliance deadline before finalizing rulemaking for test procedures and methodologies.

- Second, by failing to consider any costs related to testing procedures or compliance and enforcement, DOE failed to consider an important aspect of the problem—that is, whether the

Final Rule’s energy standards will too greatly impact the purchase price of manufactured housing or the total life-cycle construction and operating costs of manufactured housing. See Business Roundtable v. SEC, 647 F.3d 1144, 1148–52 (D.C. Cir. 2011) (“[B]y ducking serious evaluation of [these] costs,” the agency “acted arbitrarily.”).