There is no need for a Ph.D. in history to do a good report on some aspect of manufactured housing presently or in years gone by. But it wouldn’t hurt an ambitious and fearless bachelors, masters, or doctoral degree candidate(s) credentials in history (or economics, politics, legal, etc.) to dig into the topic. America has a widely acknowledged affordable housing crisis. The past is a prologue to the present. What’s happened before obviously means it is possible it could occur again. But also, what’s happened before is how we got to where we NOW are as an industry. Or something similar can be said about our nation and world, the past sheds light on how current circumstances came to be. If no degree in history or other field is needed to write a report like this one, what is useful to do a proper job? Basic journalistic skills, and/or the nose of a researcher willing to look through prior reports and remarks, apply some common sense and intellectual curiosity, and then see how those remarks frankly compare to present knowledge and circumstances.

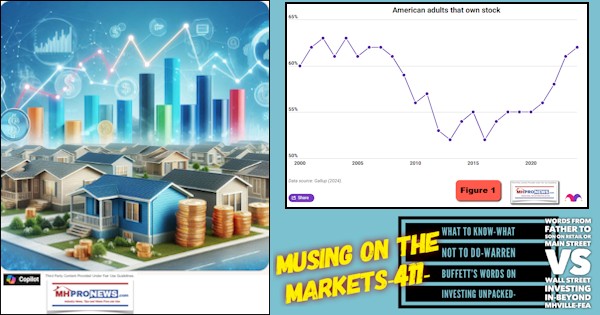

Philip L. Graham, former President and Publisher of the Washington Post is credited with saying that, “Journalism is the first rough draft of history.” Applying that notion is an example of how insights like those which follow can come to life. Let’s note anew that even if someone strongly disagrees with some of Warren Buffett’s politics or “moat” building and other practices, he has repeatedly credited reading with being an important part of his success. Buffett is said to spend 5 to 6 hours daily reading and has for decades. He is said to read history. Not just a business or industry’s history, but other history too.

Restated, Buffett’s experience is a real-world example of the ancient Latin maxim: “scientia potentia est” – which can be translated as knowledge is potential power. Sure, it helps to have billions behind that knowledge, but Buffett didn’t start out with those billions. The thirst to know combined with patience, persistence, and are part of how our industry and/or society can advance.

With that backdrop, this flashback will shed significant light on issues of importance TODAY and for what is yet to come.

Part I

Per then CBS owned MarketWatch is the following dated 11.23.2002. It is edited for length, and brackets and ellipsis (…) are added by MHProNews.

Warren Buffett apparently has his eye on a new double-wide, judging from news that his holding company just ponied up help for a bankrupt mobile-home manufacturer.

On Saturday, Oakwood Homes OKWH said that Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway…along with two other firms, have agreed to provide $215 million in debtor-in-possession financing to the troubled company, bringing its new liquidity facilities to a total of $415 million.

Oakwood announced it would take the Chapter 11 route on Nov. 15, citing “the continued poor performance of loans we originated in 2000 and before, as well as the deteriorating terms in the manufactured housing asset-backed securitization market into which we sell our loans.”

The company also said it was suffering from a declining recovery rate in the repo world, with all factors combining to result in its “loan servicing income being substantially eliminated,” while increasing the rates it has to pay for guarantees on paper it has previously issued.

Oakwood has been busily shuttering various manufacturing operations and turning out the lights on some retail operations in an attempt to stanch its losses, which totaled $119.8 million, or $12.61 per share, in its fiscal third quarter — wider than a loss of $50.2 million and $5.33 per share it recorded for the same period of 2001. …

In addition, Oakwood said it has cut a deal in principle that would give it access to an existing $200 million loan purchase facility, allowing it to continue originating loans as usual.

“We believe that the proposed $415 million of credit facilities should provide Oakwood with ample liquidity throughout the bankruptcy proceedings,” Standish said.

Under terms of the deal, when and if the company crawls out of Chapter 11, Berkshire Hathaway will become its largest shareholder. Current investors, meanwhile, will “receive a nominal value, consisting solely of out-of-the-money warrants for approximately 10 percent of the post-restructuring common shares.”

Founded in 1946, Oakwood went public 31 years ago, according to Hoover’s Online. This is its second major restructuring after a late 1980s crisis brought on by its heavy investments in Texas that went sour with the crash in oil prices. With over $1 billion in sales last year, Oakwood competes for its share of the mobile home market with companies including Fleetwood FLE, and Champion CHB…

The entire industry has been under pressure of late, even in the face of a strong housing market. Factors weighing on the sector include its higher, less competitive interest rates on loans and a propensity to go after the low-hanging fruit, i.e. customers who are typically the first to suffer the effects of an economic downturn. …”

Part II – Additional Information with More MHProNews Analysis and Commentary

As MHProNews has previously reported, there may be background evidence hiding in plain sight that the loss of the secondary market in manufactured housing was not coincidental. To update that, this question was put to Bing’s AI Chat function.

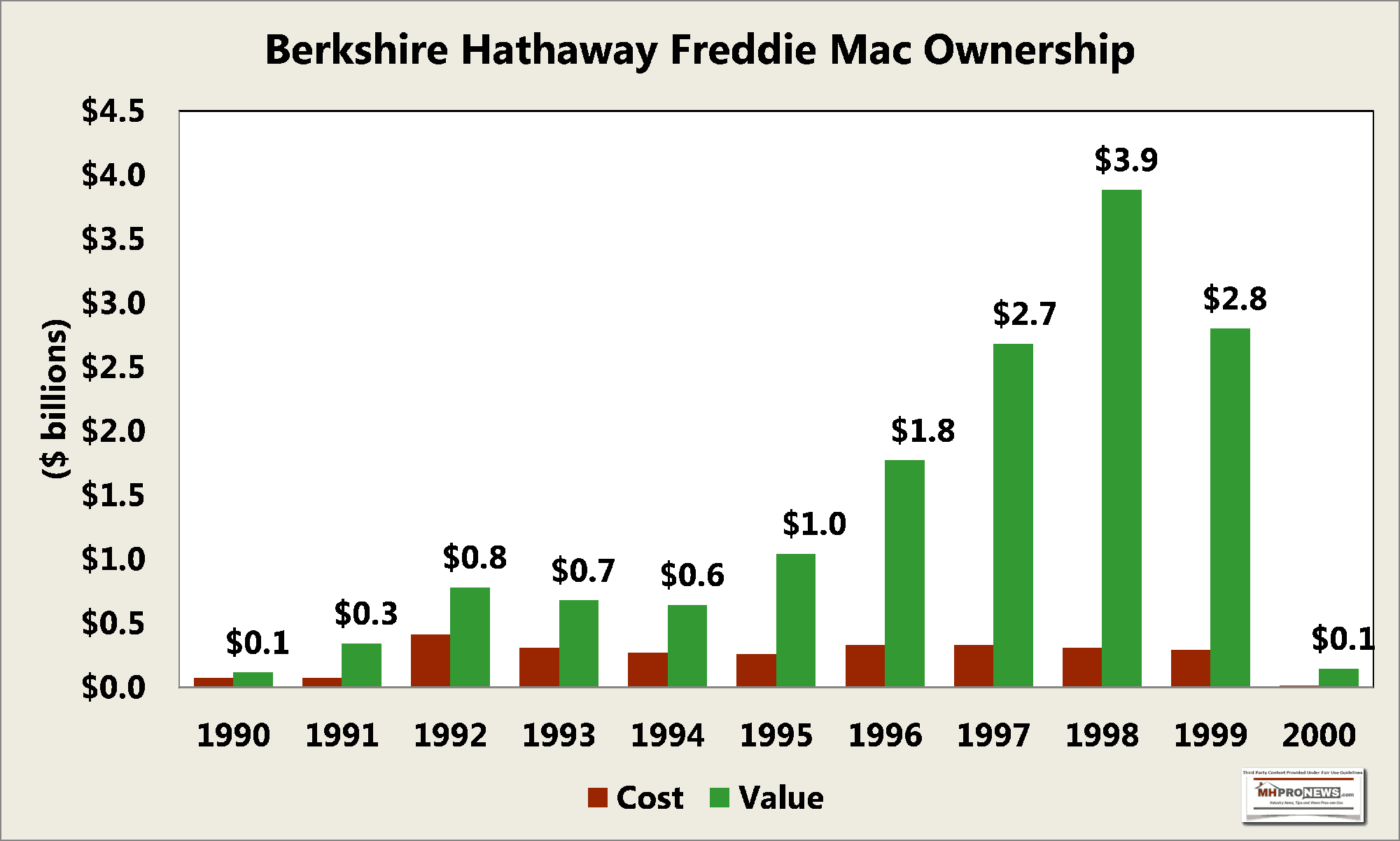

>> When did Berkshire Hathaway dump stocks in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac?

According to a Yahoo Finance article, Warren Buffet, the CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, sold nearly all of his shares in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in the year 2000. He testified to the U.S. Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission in May 2010 that he became “concerned” about their management 1.”

Buffett’s firm reportedly made healthy profits from Fannie and Freddie for years. Then he sold the shares well in advance of the financial crisis that later struck conventional housing, but which in some ways were proceeded by a similar crisis in manufactured housing.

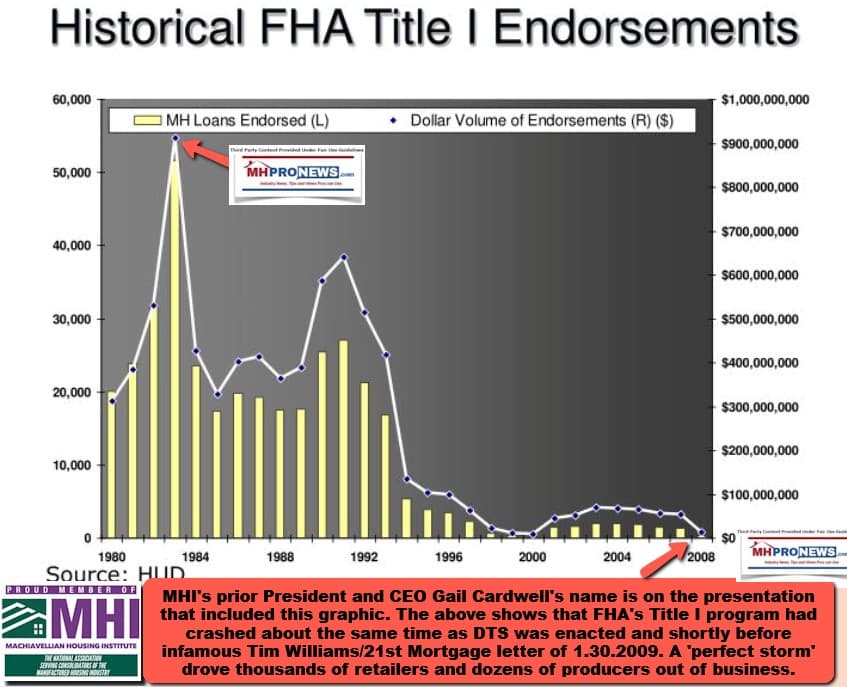

There is little doubt that ‘liar loans’ and poor underwriting standards were part of the meltdown of the manufactured housing market. That is often said about the crash of the industry in the post 1998 era. But what is often missed is that the crash of the conventional housing market was far worse. The impact on the economy and housing was devastating, as those who recall the 2008 mortgage/finance crisis will recall. Despite the high costs and deep harms, liquidity returned to the conventional housing market. Which begs the question. Why didn’t liquidity return to manufactured housing?

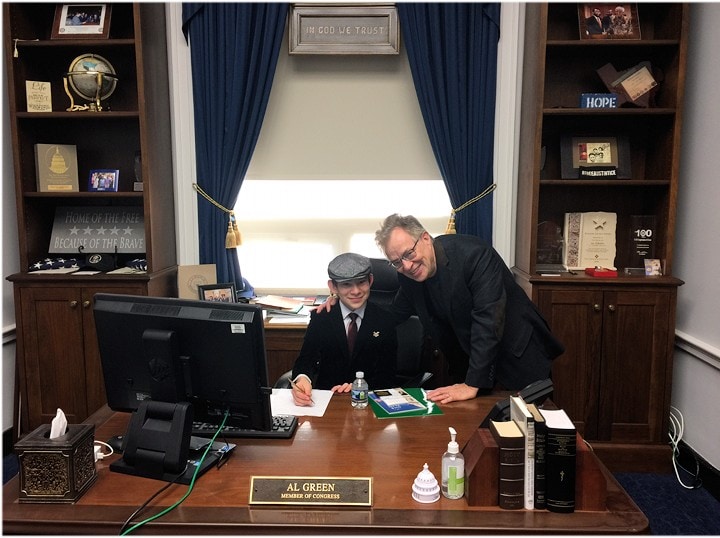

F.R. (Frances) “Jayar” Daily made remarks to Congress in 2016, in part on behalf of the Manufactured Housing Institute (MHI) in support of the then Preserving Access to Manufactured Housing Act. Daily is still on the MHI board of directors on this date, per MHI. At the time of his remarks to Congress, Daily was: “Chief Operations Officer (COO), American Homestar Corporation Director, Board of Directors of the Manufactured Housing Institute Chairman, National Modular Housing Council Immediate Past Chairman, the Manufactured Housing Division of the Manufactured Housing Institute.”

Some of what Daily said to Congress is as follows.

“Over the past eight years, the Enterprises have done little to support manufactured housing.”

Daily cited the CFPB’s 2014 research as part of your reason for saying: “In large part this disparity is due to the additional risks the lender takes on: a lack of a significant secondary market for chattel loans which may account for 100 to 150 basis points, concomitant interest rate risk, which combined may account for an additional 150 to 200 basis points, higher servicing costs and very limited risk sharing with lenders by either the private or government sectors, which may account for an additional 150 basis points.” One should presume that because those remarks were made on behalf of MHI, that MHI had lender input on those remarks. Furthermore, Daily’s firm is vertically integrated. Meaning, they may have known from their own internal data what the higher costs would be due to the lack of FHA Title I and/or Duty to Serve (DTS) mandated lending that the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) is supposed to impose and regulate on manufactured housing.

Lending is the life blood of mainstream housing and manufactured housing, as seasoned and well-informed industry pros know, and as then Harvard fellow Eric Belsky said in remarks.

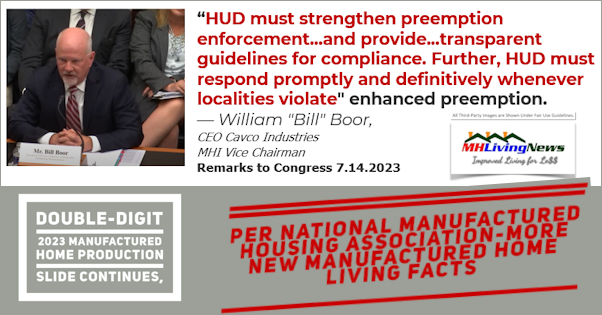

Per informed sources, FHFA Director Sandra Thompson reportedly asked for statistical information to support the case for DTS chattel lending. If so, there is something obviously wrong. Because Kevin Clayton in his remarks to Congress said that MHI and MHI members have provided such data to federal officials and others years ago.

Furthermore, the fact that Triad Financial Services, Cascade Financial, and others have been making loans profitably and sustainably for years should make it self-evident that the GSEs can do the same.

As the second article linked above indicated, there are those in manufactured housing that see possible risks and dangers in the manufactured housing market from the Skyline-Champion (SKY)-ECN Capital-Triad Financial Services (TFS) moves. Given the history of the manufactured home industry, particularly in the late 20th and the 21st centuries periodically been recalled here on MHProNews and our MHLivingNews sister site, the concern about limited financing options ought to be near top of mind and clearly must be addressed. MHI claims to be interested in that, though Doug Ryan with Prosperity Now (previously known as CFED) and others don’t buy their sincerity. Ryan, for example, has said that the status quo benefits Buffett’s brands like Clayton Homes, 21st Mortgage Corporation (21st), and Vanderbilt Mortage and Finance (VMF).

Hold those thoughts, as we pivot to insights from Jennifer Reingold via Fast Company on 1.1.2004. This flashback, is arguably as – or perhaps more – interesting now as it was when she first published this approaching 20 years ago. As with the MarketWatch flashback report above, ellipsis (…) are items edited out for length. “Jennifer Reingold…is a Fast Company senior writer.”

The Ballad of Clayton Homes

Berkshire Hathaway’s $1.7 billion acquisition of a mobile-home company seemed like a perfect match. Then shareholders got a look, and a folksy tale suddenly turned ugly.

Warren Buffett sat in Omaha, Nebraska, bushy eyebrows knitted as he tried to get his voice in tune, via speakerphone, with a guitar in Maryville, Tennessee. On the other end of the line, strumming away, was the affable, homespun Jim Clayton, chairman of the $1.2 billion manufactured-housing giant Clayton Homes, the latest catch in Buffett’s billion-dollar acquisition net. The two were practicing for a musical meeting that would introduce Buffett to Clayton’s employees and, hopefully, pave the way for a smooth transaction.

It was a fitting scene. If it were a country song, the saga of how Warren Buffett managed to take control of the company might be the kind of downbeat ditty that would have listeners crying in their beer. It’s a story of love gone wrong for many outside shareholders, who believed their company was worth far more than what Buffett offered for it and who fought passionately for their prize only to find betrayal and heartache at the bitter end. The notes of this song ring truer for those connected to the Clayton family. In their eyes, it’s a blood-pumping anthem of triumph over adversity. Clayton, 69, a helicopter-piloting musician and son of a sharecropper from the Tennessee sticks, made it big–real big. Then, against all odds, he and his son Kevin sold the publicly traded company to the world’s most respected investor, saved the community, and got to live happily ever after.

The truth, as in most ballads, bar fights, and divorces, lies somewhere in the middle. Here, then, is the tale of a prominent Tennessee family, rich in stock but relatively poor in cold hard cash, that bit and bit hard when the oracle of Omaha suddenly decided that there was mobile-home gold in the rolling hills outside Knoxville. The struggle that ensued entangled an angry bunch of Denver-based butchers, the most shark-toothed class-action lawyers in the business, and even former vice president Dan Quayle before the deal finally went through (although investors have filed a lawsuit against Clayton and its board).

What we are left with is a darn good yarn about how what began as a cordial meeting of the minds quickly turned into one of Buffett’s toughest acquisitions. The Clayton story shows how Buffett’s gimlet eye for a good buy is a great thing–as long as you’re on the right end of the deal. For the Clayton family, the buyout was the ultimate validation of an enterpreneurial dream; for the outside shareholders, it reeked of a sweetheart setup that couldn’t possibly be fair if the world’s sharpest value investor wanted in. No one lost it all–the shareholders were paid in cash and the company continues onward–but did anyone other than the Clayton family and Warren Buffett really win?

The battle for the hearts and minds of a company better known for double-wides than charges of double-dealing began back in February of 2003, when a group of students at the University of Tennessee B-school prepared for the most important professional day of their young lives. Thanks to a relationship cultivated over the years by UT finance professor Al Auxier, 40 members of the school’s Financial Management Association had flown to Omaha to visit Warren Buffett himself. Buffett is known for his low profile, but for the past six years, he has invited the group to spend a day at Berkshire Hathaway sipping Cherry Cokes, nibbling on See’s Candies, and chatting about investments, the economy, and whatever else strikes their fancy. The 2003 meeting was held on February 3, in the middle of a blizzard that had some students fretting–or perhaps hoping–they’d be stranded in Omaha. “We weren’t used to seeing that kind of snow,” laughs Angel Norman, an MBA student.

Although Buffett had recently dipped a toe into the manufactured-housing market by investing more than $200 million in the debt of bankrupt Oakwood Homes, the UT students knew more than he did about Clayton Homes, which is headquartered just outside Knoxville, in neighboring Maryville. Jim Clayton, a UT alum, has contributed generously to the school and donated funds for the students’ group to use in investment contests. Professor Auxier and Jim Clayton are friends. And one of the students visiting Omaha, Richard Wright, was actually working part-time as an intern for Clayton.

So when the group was searching for a gift for Buffett, they seized on First a Dream (FSB Press, 2002), Clayton’s folksy, chatty 2002 autobiography detailing his rise from the feed-sack-wearing son of a cotton farmer to a mainstay on the Forbes 400 list of the wealthiest Americans. Clayton started the company in 1966 with one charred mobile home that he and his parents renovated and resold. By 2002, Clayton Homes reached $1.2 billion in sales and was the pride of its industry.

“We had run out of ideas” for gifts, says Auxier, whose previous presents to Buffett included an autographed football from the coach of the 1998 UT national champions, Phil Fulmer. This time, Wright, a senior, was the official emissary. “After [the Q&A], we went to go and take pictures, and I handed him Mr. Clayton’s book,” said Wright. “I said, ‘I’ve been working with Mr. Clayton. These are your types of people.’ ”

As the legend goes, Buffett was so inspired by Jim Clayton’s book that he decided to buy his company. But as with so much else in this story, there’s a harder-edged reality beneath the folksy myth.

Buffett’s response: “Well, tell [Clayton] he deserves a raise.” By the time Wright brought Jim Clayton an autographed picture of Buffett holding the book, Buffett had already read it. As the legend goes, and as local papers and The Wall Street Journal have reported, Buffett was so inspired that he called Kevin Clayton, Clayton Homes’ CEO, to begin serious discussions about buying the company, which by all accounts had never been for sale. (Buffett’s code name in the talks: Mr. Sunshine.)

But as with so much else in this story, it turns out that there’s a harder-edged reality beneath the folksy mythmaking. Buffett did not come across Clayton Homes completely by charming happenstance. Kevin Clayton initiated the contact, Auxier says, asking him to tell Buffett that the company was interested in exploring “a business relationship.” That relationship quickly blossomed into Buffett’s all-cash offer on April 1 to buy Clayton Homes for $12.50 a share, a 12.3% premium over the March 31 price. The Claytons leaped at the chance to become part of the Berkshire Hathaway empire. And Wright woke up one morning to see a picture of himself handing Buffett the book splashed across the front page of the business section of the Knoxville News-Sentinel, with the headline “Gift of Book Sparks Transaction.”

Clayton’s management and board has portrayed the offer as being as serendipitous as the sudden appearance of a rainbow on a gloomy day. Certainly, it made sense for Jim Clayton himself, who had turned over the day-to-day reins of the company to Kevin in 1999 but remained chairman; it allowed him a way to monetize the 28% of the stock he and his family foundation controlled for $470 million in cash without dumping his holdings on the open market. “They were rich, but rich on paper,” says Greg Taxin, CEO of proxy adviser Glass, Lewis & Co. “The minute they sell a single share, the thing would tank. Along comes Warren Buffett.” For Clayton’s other executives, Berkshire’s reputation for buying well-run family businesses and leaving them be seemed like ideal job security in a time of relative trouble. Also appealing was Berkshire Hathaway’s AAA debt rating, a huge edge for a company as dependent on financing as Clayton.

Certainly, things in manufactured housing were not going smoothly. The industry had fallen into one of its worst down cycles in decades, as its overly aggressive lending practices sparked a boom that low interest rates for “real” houses helped turn into an enormous bust. The stock had fallen from a high of $19 in 2002 to its current $11, and earnings in 2003’s third fiscal quarter were down 10%. The company’s dependence on its financial-services unit, which had provided most of its profits in recent months, was seen as a risk. And the Iraq war, which began March 18, had driven down the overall stock market as well. It looked like a good time for value hunting.

At least that’s what Buffett, the master of the no-hassle bargain-basement deal, thought. But country songs are filled with twists and turns, and this one was no different. Investors considered Clayton Homes to be the premier player, boasting an efficient vertical model with 20 manufacturing plants, almost 300 company-owned stores, hundreds of independent retailers, 86 manufactured-housing communities, and mortgages for some 168,000 people. Even the homes themselves have a superior look and feel. No tornado traps, they often sit on basements, boast slanted roofs, and, if you weren’t there on drop-off day, could fool anyone. A five-bedroom Norris Home, one of Clayton’s high-end brands and priced at about $60,000, features a working fireplace, a whirlpool bath, stainless steel sinks, a surround-sound stereo system, and GE appliances.

Certainly, the Claytons hadn’t signaled a major problem: At the second (fiscal) quarter conference call for 2003 in January, Kevin Clayton, while bemoaning the state of the industry as being in a “full-fledged meltdown,” also took pains to differentiate his own company’s prospects. “We have a better model,” he said. “You’re not comparing apples to apples.” Indeed, investors had held on to Clayton precisely because it had for years pursued a careful strategy while rivals such as Oakwood Homes lent their way into bankruptcy. At Clayton, dealers were required to bear much of the financing risk of their sales–giving them an incentive to find good customers, not just customers. Investors also believed in management and in the company’s relatively pristine balance sheet.

…

Clayton was anything but a sucker. He never overpaid for an asset, prided himself on giving his customers good value, and even outsmarted his way out of bankruptcy when a local bank that had overextended itself suddenly foreclosed on his car lot. (Clayton was savvy enough to buy back the repossessed cars in an auction, using cash committed by customers who trusted him.) With Clayton Motors, and later Clayton Homes, he became famous throughout the South as a master of the deal who prided himself on rooting out the diamond chips in other people’s trash piles. From cars, Clayton moved to homes, where he grew with a strategy of careful expansion, decent pricing, and high quality. “He’s value-driven in everything he buys,” says Tom Gunnels, a friend and tennis partner of Clayton. “Whether it’s a pair of tennis shoes or a helicopter, he shopped around until he found the best deal.”

Never had he accepted the first bid on anything–until now. So how was it, wondered many shareholders, that such shrewd businessmen as Jim and Kevin Clayton would leap at what seemed to be such a low offer when the industry had already hit bottom? Why not try to beat the bushes for a better bid? Could it be that the family’s interests had diverged from those of its other shareholders? “I was in shock that night,” says Carl Tash, CEO of Cliffwood Partners, a real-estate investment firm that held 1.2 million Clayton shares. “For a year we had been telling our investors that it would be a $20 stock. I thought it was an April Fools’ joke.” Tash was particularly upset because the previous October, he had offered Kevin Clayton help financing some newly purchased loan portfolios. “His point to us,” says Tash, “was that it’s a lucrative business, and we will do it ourselves.” Both Claytons refused to comment on this point or any others, citing the ongoing litigation.

Quickly, opposition to the deal began to form. One criticism centered on the quality of the fairness opinion of Morgan Keegan, a local investment bank. Orbis Investment Management, the fourth largest holder of the stock with some 5%, complained that the bank didn’t appropriately value the company. Proxy adviser Glass, Lewis & Co. figured the company was worth between $15.80 and $17.20 a share, well above Buffett’s offer. Shareholders also noted that the stock prices of both Clayton and its peers had risen significantly since the offer was made, as the stock market surged. Clayton itself traded above Buffett’s offer for the entire month of June, indicating that people expected either a better price or that the deal wouldn’t close.

Dan Quayle showed up–representing a hedge fund named for the three-headed dog guarding the gates of hell.

Suddenly, the Claytons found themselves in the rather unusual position of having to convince investors of how bad their business was. Complicating matters was the general sense that if Buffett bids for something, it must, by definition, be undervalued. Michael Winer, portfolio manager of the Third Avenue Real Estate Value Fund, called Buffett as a courtesy before he issued a press release blasting the deal. “He tried to convince me that I was wrong,” Winer says. “We agreed to disagree, but it was interesting to hear Warren Buffett say how bad a business it was, and he’s paying $1.7 billion.” Buffett wouldn’t comment.

Shareholders were also worried about Clayton’s record of corporate governance. In 2002, the Council of Institutional Investors put Clayton on its “focus list” of underperforming companies and criticized the company’s independence standards. Of the then-seven directors, three were Claytons, there was no nominating committee and a compensation committee board member, Thomas McAdams, was a partner at the company’s primary law firm. Another outside member, C. Warren Neel, who currently heads up the UT’s new Center for Corporate Governance, is a scuba-diving and skiing buddy of Jim Clayton and his wife Kay, and advised Clayton on the purchase of some local banks. Clayton calls McAdams “my special friend” in his autobiography and includes several photographs of Neel and his wife in social situations. “There was reason to doubt that this company had in its DNA the right level of care and responsibility to shareholders,” says Glass Lewis’s Taxin.

An episode recounted in First a Dream adds to those doubts. About a decade ago, an independent board member enraged Clayton by demanding an investigation into a dispute with an outside auditor. Dismissing the investigation as a pretext for steering business to a local law firm, Clayton persuaded the board to vote, six to two, to suspend it. The two dissenters resigned. From then on, the board was peopled with friendlier types, all of whom supported the Buffett offer. After the failure of separate attempts by Orbis and others to block the sale or require that it go through only if a majority of independent shareholders voted for it, the Clayton shareholders meeting was set for July 16, 2003 at 11 a.m. The sense was that the vote would be very close. Strangely, proxy adviser Institutional Shareholder Services supported the deal while its own subsidiary, Proxy Voting Services, opposed it. No one knew what to expect when they walked past the two black stone lions proudly guarding the Clayton Homes headquarters that morning.

What followed was a shareholder meeting like no other. The appointed hour came and went with no executives to be found. The crowd began to grow restless, until finally, at about 11:25, Jim Clayton entered the room. Gone was the fun-loving man who enjoyed getting people in the mood with a tune or two. This time, says Steve Parham, a shareholder and attendee, he looked “somber.” “These things can get complicated,” Clayton said, explaining that Kevin wasn’t there because he was on the phone with some shareholders.

Although the first item on the agenda was the vote, Clayton suddenly decided to take investor questions. “He was clearly nervous and clearly stalling,” says William B. Gray, president of Orbis. According to attendees, virtually all of the questions that followed were negative in tone. Finally, Tash, the head of the firm that held a chunk of Clayton stock, stood up. “The purpose of this meeting was to have a vote,” he announced, “and I’m asking you to call for a vote.” Clayton’s reaction, according to the affidavits of several people there, was bizarre. He looked at a colleague standing by the door and asked, “Is there any change?” The man shook his head no. Clayton, rather than responding to Tash’s request, immediately announced an adjournment for lunch. In a deposition, Clayton later testified that he had no recollection of the request for a vote.

…

Kevin Clayton announced that three large institutional shareholders had asked for a two-week adjournment so the company could have a chance to attract other bidders. Gray later said he talked to two of the investors and they both denied making the request. He also charges that Clayton set voting rules on the motion to adjourn that guaranteed it would pass. Gray, furious, asked for a vote on the merger itself, but Clayton said that the motion to adjourn superseded that vote. The meeting ended in confusion.

Behind the scenes, it turned out, Kevin Clayton had learned that Fidelity–which as of March 31 had been the second largest shareholder with 8.5% of the vote–had accidentally voted in favor of the deal, despite its policy in contested mergers of withholding votes until the last second, and wanted to pull back its support. Suddenly, the Claytons were looking at possible defeat rather than a narrow victory. That day, according to the deposition of Berkshire CFO Marc Hamburg, Clayton executives spoke with Buffett’s people, who agreed to put off the deal a little bit longer in return for a $5 million fee. Buffett reiterated that he wasn’t going higher. The company hadn’t pressed him before. Why should he change now?

Allen Goolsby, an attorney representing Clayton Homes at Hunton & Williams based in Richmond, Virginia, says the adjournment was simply a way to be responsive to shareholders and give other bidders a chance. But angry shareholders believe that Clayton adjourned the meeting rather than hold a vote the company knew it was about to lose. “We came prepared on the 16th and we won,” says Tash. “We played by their rules, and they moved the goal line.”

“It was interesting to hear Warren Buffett say how bad a business it was, and he’s paying $1.7 billion.”

By now, all that sweet music Buffett and Clayton had made together was a distant memory. On July 25, an institutional shareholder, the Denver Area Meat Cutters and Employers Pension Plan, which held some 45,000 shares, suddenly filed suit in Blount County Circuit Court, charging “self-dealing, abusive control, and lack of candor” on the part of Clayton Homes. Who was representing this heretofore-unknown group of red-blooded activists? Milberg, Weiss, Bershad, Hynes & Lerach LLP, the New York law firm whose name strikes fear in the heart of any public company executive. “They sold the company in a way that hurt our members,” says Ernest L. Duran Jr., president of the United Food and Commercial Workers Local 7 in Wheat Ridge, Colorado, the umbrella union that includes the Meat Cutters (which still has a separate pension fund). “Our larger concern is to keep corporations more accountable.” Darren Robbins, the tough-talking Milberg attorney, puts it more bluntly. “Their shutting down the meeting,” he says, “was akin to [former California governor] Gray Davis ordering the National Guard to shut down the polls. It’s a well-known fact that they committed a fraud.” Other suits continued in Delaware, creating still more confusion because there were similar cases in different jurisdictions.

Then, another potential suitor emerged–a secretive hedge fund called Cerberus Capital Management, named for the three-headed dog guarding the gates to Hades. Cerberus, which in partnership with others had recently outbid Buffett by spending more than $650 million for Conseco’s mobile-home lending unit, had written to Clayton expressing possible interest a few days before the meeting. On July 21, Cerberus and its chairman of global operations, former vice president Dan Quayle, showed up to kick the vinyl siding. Some 50 due diligence specialists spent more than a week holed up in high-end double-wides adjoining the main offices and pored over the books. Quayle played the good-cop role, shaking hands and assuring the community that Cerberus’s intentions were true. “This is an important company to Knoxville, and we understand that,” he told the Knoxville News-Sentinel. “You’ve got good management–the issue is capital.”

But if Clayton was in earnest about attracting bids to rival Buffett’s, it also must have known that there was one big roadblock to any other transaction. According to the proxy, competing bids could be considered for just a little over a month. If another bid came in after that, the 28% stake owned by Jim Clayton and his foundation would still remain committed to Buffett’s deal for another 12 months. With only about 80% of shareholders likely to vote, virtually every single remaining vote would have to support an alternative bid for it to have any hope of going through. In the end, Cerberus decided not to bid.

On July 30, the adjourned meeting finally came to order, starting on time and following the set agenda. The deal barely passed, with just 52.3% of shareholders voting in favor, including the 29% owned by the family/management block. That meant outside shareholders voted against the deal by more than two-to-one, points out Jerry V. Bruni, president of J.V. Bruni & Co., a Colorado-based money-management firm that held about 308,000 shares. “Opposing anything management supports is unusual,” Bruni says.Buffett would take control of Clayton Homes, at the original offer of $12.50 per share, even as the S&P 500 rose 15% and the manufactured-housing industry had bottomed out, although it hasn’t yet gone into recovery.

Just to be sure, after an August 6 ruling in Blount County allowed the deal to go forward, Clayton filed merger documents at the crack of dawn allowing it to delist the stock. “The filing was done carefully and consciously,” says Goolsby, the Clayton attorney. The company knew that it would be incredibly difficult to reverse a merger once the stock had stopped trading. A flurry of appeals and counterappeals by the Meat Cutters and Clayton followed, leaving the merger in a legal no-man’s land where the stock no longer traded, but Buffett hadn’t paid the shareholders, either. Finally, on September 3, the appeals court ruled that there was “not a scintilla” of evidence of fraud that should keep the merger from being consummated. Said a jubilant Kevin Clayton in a statement: “I hope this puts a stop to the character assassination that has been all too common in this lawsuit.” A final appeal failed, but the court did allow the plaintiffs to pursue a class-action suit to try to recover damages from the Claytons and the board. It’s in process today.

…Buffett returned to Knoxville on October 14 to thank the 40 UT students who had visited him in Omaha the previous winter. In the University Center Ballroom, he gave a speech, then donned a mortarboard and pulled out a stack of leather binders. As he called the name of the students, he handed each a certificate that bestowed an honorary PhD “to this phenomenally hardworking deal maker in appreciation for your insights and advice in the Clayton Homes acquisition,” signed by “Dean/Chairman Warren E. Buffett.” Along with each diploma was one share of Class B Berkshire Hathaway stock, valued at about $2,700. For Professor Auxier, there was an even better prize: a Class A share, worth about $81,000. The students were thrilled, although Wright jokes that a proper finder’s fee for the deal would have been more like 1%, or $17 million. And so ends the ballad of Clayton Homes–once again with a pleasing, homespun passage that seems to conceal a sour note. Was Clayton Homes sold for a fair price, or for a song? ##

Per Kevin Clayton in a video with transcript linked here, the suit was “ugly.” In that same video interview, Clayton defended the deal made with “Warren.”

Note that the above from Reingold via Fast Company mentioned, among other things, “Third Avenue Real Estate Value Fund.” Third Avenue was part of the picture in the history of Cavco Industries too.

No report, no matter of what length, can possibly cover everything related to even a focused topic. That said, among the points the Fast Company article didn’t mention is that the #3 and #4 companies in manufactured housing were being united via the Clayton deal with Berkshire. Oakwood would get rolled into the Clayton ‘family of brands’ as they sometimes colloquially say.

Due in part to the lack of lending following the GSEs withdrawal from the manufactured housing marketplace, with Berkshire’s backing, Clayton no longer had a need to raise capital to make loans, as Kevin himself said. Likely thousands today involved in manufactured housing did not work in the industry in the 2009-2010 timeframe, much less then 2000-2003 timeframe. They may not know or recall the possibility how the past loss of manufactured home lending could occur once more. Reingold didn’t mention the Buffett-Clayton “moat” either.

The point previously made by Kevin Clayton about sustainability for manufactured home lending have been reported in articles like the ones posted below.

These are just some of the articles and factoids that could be presented for industry professionals, investors, public officials, attorneys, and affordable housing advocates to consider when it comes to the history of manufactured housing in the 21st century. With that backdrop and encouraging all readers to check out the headlines for the week in review from 9.9 to 9.17.2023 that follow and today’s postscript. With no further adieu, here are those headlines and linked reports. Each in various ways shed light on aspects impacting our nation and industry.

What’s New on MHLivingNews

What’s New from Washington, D.C. from MHARR

What’s New on the Masthead

What’s New on the Daily Business News on MHProNews

Saturday 9.15.2023

Friday 9.14.2023

Thursday 9.13.2023

Wednesday 9.12.2023

Tuesday 9.11.2023

Monday 9.10.2023

Sunday 9.9.2023

Part IV – Postscript

“News through the lens of manufactured homes and factory-built housing.” ©

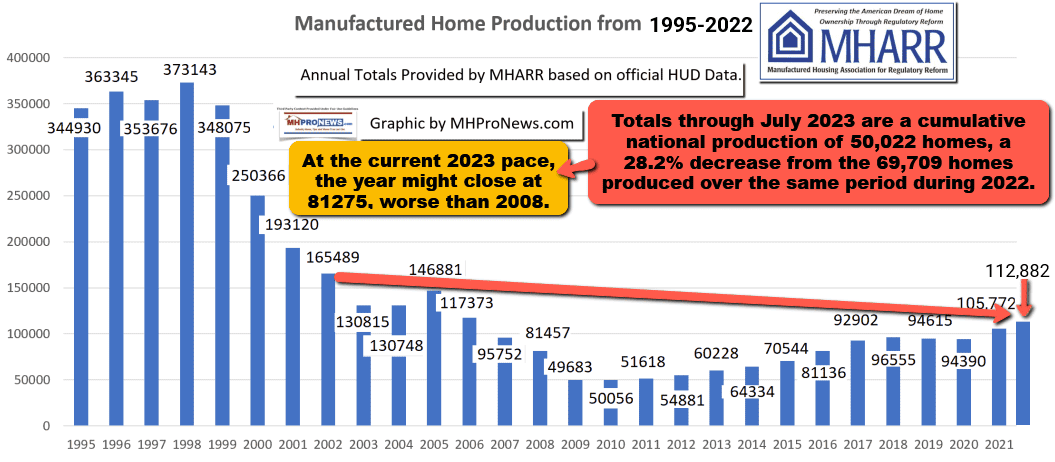

That is an aspect of our reports rarely, if ever, found on some of our would be rivals that tend to be closely aligned with MHI. The industry is in yet another 21st century downturn. There seems to be no real sense of urgency at MHI to change the industry’s current dynamics. They may, from time to time, have a staff or corporate leader say something that sounds good and may seem similar to what – for instance – MHARR has been saying for years. But the fact that MHI leaders don’t seem to routinely go beyond mere words, photo ops, and mutual or self-praise yields the status quo. That status quo benefits consolidators.

MHI staff or corporate insiders/outside attorneys/key members have thus far been silent on the issue of the class action antitrust lawsuit. That big class action suit in some ways underscores concerns raised by MHProNews/MHLivingNews for years. So, the suit is ‘no surprise’ – other than perhaps, what took you so long?

In fairness, it takes time to prepare such a suit. So, when MHProNews reported last year that the industry could be facing a new era of litigation, keep that foreshadowing in mind. Because since it has happened before, it can happen again.

The Skyline Champion- (SKY) Regional Homes deal is a reminder that consolidation is continuing. An apparent consequence of the Buffett entry into MHVille has been the tidal shift away from industry growth which resulted in steady consolidation. Presuming the accuracy of Reingold’s report for Fast Company, apparently, the Buffett-Clayton nexus felt there was a need to have a ‘cover story’ in place to cement that deal. If there was nothing to hide, why the folksy ruse Reingold laid out?

The industry is once again in reverse. There has been talk for months by the multiple MHI-linked statements produced by the Texas Real Estate Research Center (TRERC) and the TMHA saying that a turn-around is coming. Where is it? Is that just another Preserving Access style head fake? Is it like a decade-plus talk of more lending, while lending is once more apparently contracting?

Or is it like years of talking about the “enhanced preemption” provision of the MHIA 2000, with MHI still giving no indication of launching litigation to enforce that aspect of federal law? MHARR’s Mark Weiss, J.D., called MHI and their related ‘partners’ in this status quo mess a “shell game.”

Danny Ghorbani, ex-MHI vice president and MHARR’s founding president and CEO, pointed out the years of talk, photo ops, and posturing without measurable and performance-based behavior from MHI.

There is a need to shake up the status quo. A fresh, multi-pronged push is underway to disrupt the status quo, apparent through litigation and the possible formation of a new post-production trade group that can team up with MHARR to push for authentic growth instead of talking about it. Check into the related reports to learn more and watch for fresh data and insights in the week ahead.

Again, our thanks to free email subscribers and all readers like you, as well as our tipsters/sources, sponsors and God for making and keeping us the runaway number one source for authentic “News through the lens of manufactured homes and factory-built housing” © where “We Provide, You Decide.” © ## (Affordable housing, manufactured homes, reports, fact-checks, analysis, and commentary. Third-party images or content are provided under fair use guidelines for media.) See Related Reports, further below. Text/image boxes often are hot-linked to other reports that can be access by clicking on them.)

By L.A. “Tony” Kovach – for MHProNews.com.

Tony earned a journalism scholarship and earned numerous awards in history and in manufactured housing.

For example, he earned the prestigious Lottinville Award in history from the University of Oklahoma, where he studied history and business management. He’s a managing member and co-founder of LifeStyle Factory Homes, LLC, the parent company to MHProNews, and MHLivingNews.com.

This article reflects the LLC’s and/or the writer’s position and may or may not reflect the views of sponsors or supporters.

Connect on LinkedIn: http://www.linkedin.com/in/latonykovach

Related References:

The text/image boxes below are linked to other reports, which can be accessed by clicking on them.’