Before diving into the concept outlined and ways that it might benefit manufactured housing and our American home-buying public in general, let’s define the legal term, “writ of mandamus.”

From Princeton’s WordNet:

“mandamus: an extraordinary writ commanding an official to perform a ministerial act that the law recognizes as an absolute duty and not a matter for the official’s discretion; used only when all other judicial remedies fail.” –

http://wordnetweb.princeton.edu/perl/webwn?s=writ of mandamus

Without giving away any of the story-line of his page-turning novel, let me observe that the book Writ of Mandamus by MHI’s VP and General Counsel – Rick Robinson, JD – indirectly brought this notion to mind.

MHProNews asked 4 attorneys – each one directly engaged and seasoned in manufactured housing issues – about this concept. Some of their off-the-record-comments will be shared herein.

The premise of the writ is noted above. A judge is asked via a pleading to issue a writ of mandamus commanding an official to do something in his or her official capacity. Wikipedia says:

“Mandamus may be a command to do an administrative action or not to take a particular action, and it is supplemented by legal rights. In the American legal system it must be a judicially enforceable and legally protected right before one suffering a grievance can ask for a mandamus.”

“Legal Requirement:

“The applicant pleading for the writ of mandamus to be enforced should be able to show that he or she has a legal right to compel the respondent to do or refrain from doing the specific act. The duty sought to be enforced must have two qualities: It must be a duty of public nature and the duty must be imperative and should not be discretionary. Furthermore, mandamus will typically not be granted if adequate relief can be obtained by some other means, such as appeal.”

Perhaps the most famous case requesting such a writ was the case of Marbury vs. Madison, in 1803. Wikipedia says:

“Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case in which the Court formed the basis for the exercise of judicial review in the United States under Article III of the Constitution. The landmark decision helped define the boundary between the constitutionally separate executive and judicial branches of the American form of government.

“The case resulted from a petition to the Supreme Court by William Marbury, who had been appointed Justice of the Peace in the District of Columbia by President John Adams but whose commission was not subsequently delivered. Marbury petitioned the Supreme Court to force the new Secretary of State James Madison to deliver the documents. The Court, with John Marshall as Chief Justice, found firstly that Madison’s refusal to deliver the commission was both illegal and remediable.

“Nonetheless, the Court stopped short of compelling Madison (by writ of mandamus) to hand over Marbury’s commission, instead holding that the provision of the Judiciary Act of 1789 that enabled Marbury to bring his claim to the Supreme Court was itself unconstitutional, since it purported to extend the Court’s original jurisdiction beyond that which Article III established. The petition was therefore denied.”

Having established the concept of a mandamus action, let’s suggest the following ways such an action might be used to protect Manufactured Housing specifically, or Americans in general.

1. Mandamus to FHFA to implement HERA 2008’s DTS

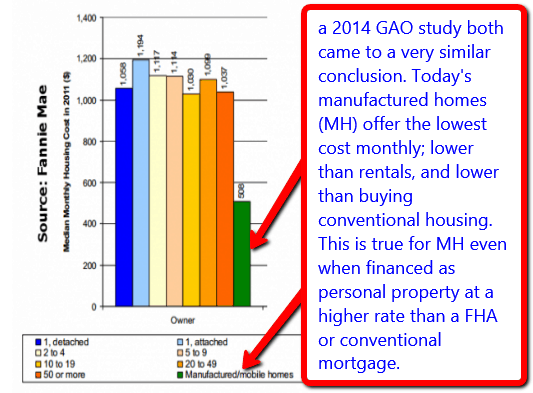

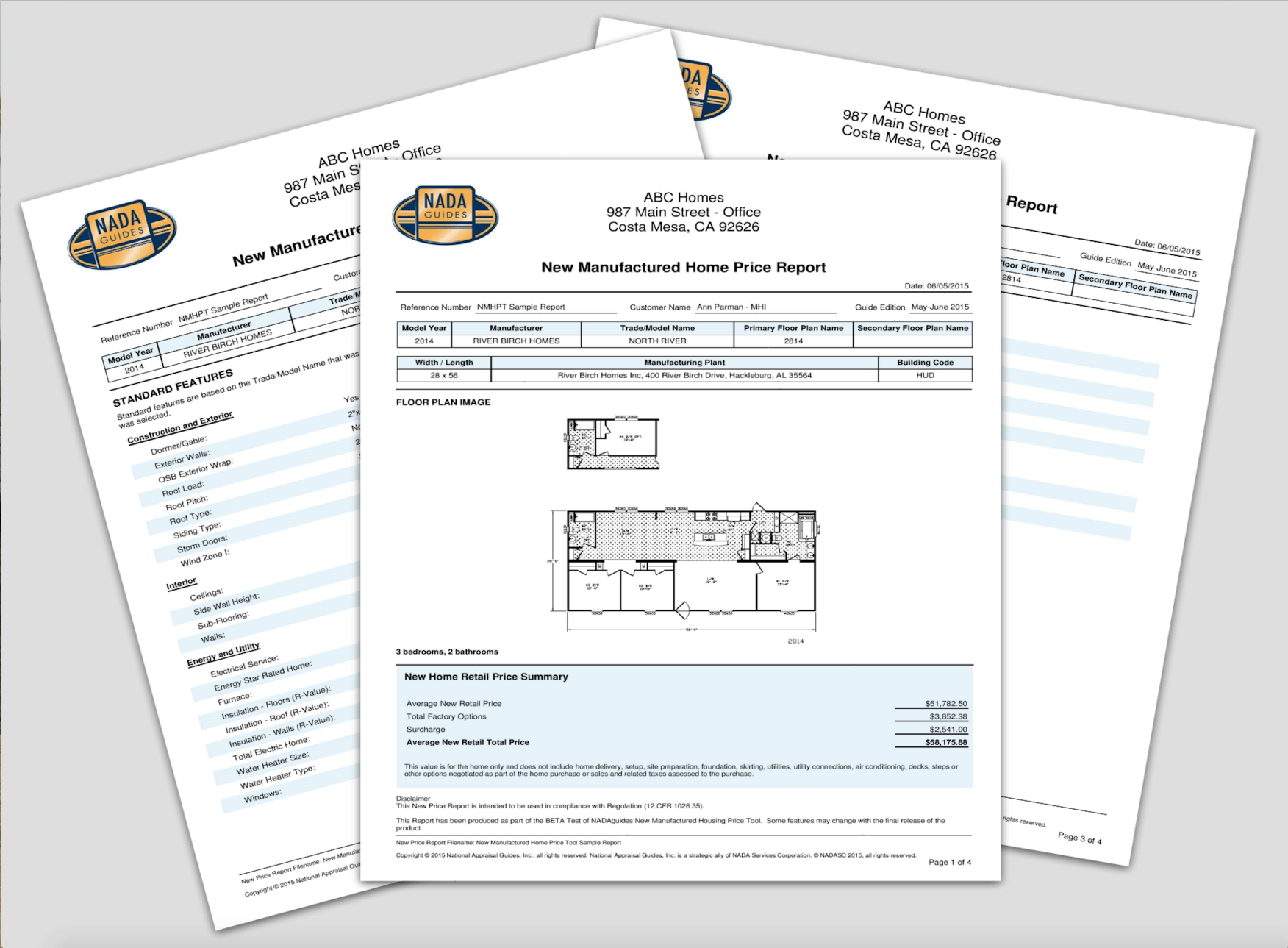

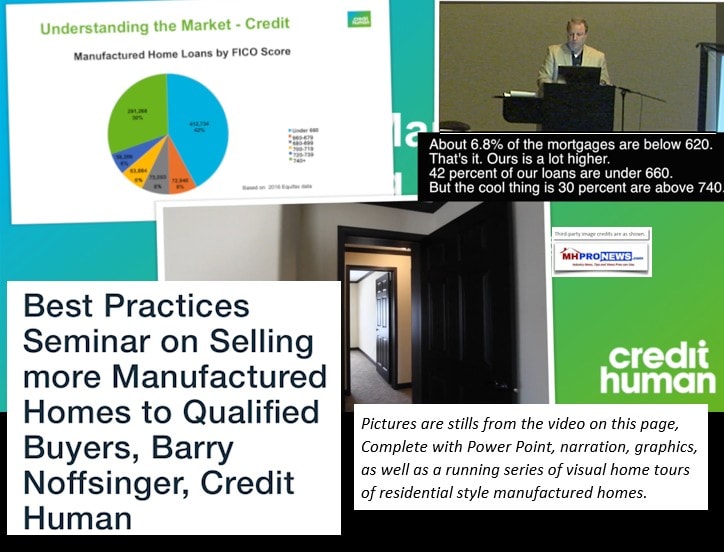

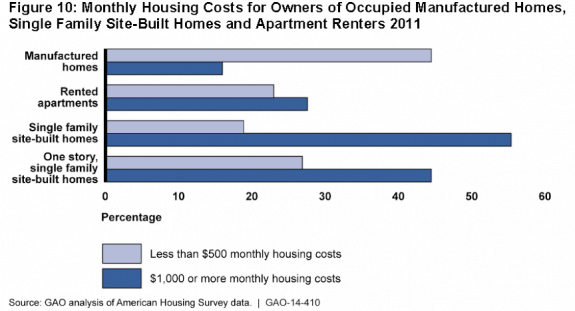

Do we want more financing? HERA 2008 established the so-called Duty to Serve undeserved markets, specifically including manufactured housing.

2. Mandamus to HUD fully implement the MHIA of 2000

Do we want less of a regulatory choke hold over manufactured housing? The Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000 (MHIA 2000) has been in place for some 13 years, and is not yet fully implemented.

While mandamus is not often used, we are in rather extraordinary times and circumstances.

Comments from seasoned and respected Manufactured Housing connected Attorneys

The first draft of this article included 3 items that might be options for a Writ of Mandamus. The two shown above are what this attorney’s comments refer to:

“Mandamus would work for either of the…” two which remain in this revised article. That attorney went onto state:

“The devil (as always) is in the details. First there may well be federal administrative steps (file a complaint or petition with this or that governmental body, etc.) that may be a jurisdictional prerequisite to filing in federal court.”

“Next, the bureaucrats will claim they ‘..are working on it’ and the courts may ‘defer’ to the administrative agency.”

“Finally where is the $$$ to pursue such a strategy going to come from?”

Another attorney stated in part as follows. Like the attorney above, this counselor thought the third topic ought to be dropped entirely (which as noted, we did drop that from this report). We pick up this lawyer’s thought here:

“…That being said, there may be a tiny bit of hope under the MH specific provisions. The federal courts have been very reluctant to use Mandamus, and even then it’s mostly used within the federal court system as a tool for Orders that go beyond proper bounds.”

“However, back in August, the DC Circuit issued a Writ of Mandamus in the Yucca Mountain case which required the agency to meet its statutory responsibility. I haven’t looked at the Duty to Serve or MHIA provisions to know whether they would fall under ministerial duty or discretion. I also don’t know what their funding looks like, which could also be a factor.”

“I would keep a close eye on what happens with the Yucca Mountain case to see if it provides any additional ammunition to use.”

Attorney Three wrote…”…a viable legal option.”

The third attorney said in part,

“Several attorneys I have spoken to have agreed that a Writ of Mandamus for FHFA to implement the HERA 2008 DTS. There is a mandate to serve underserved demographics such as low income housing.”

“The question is who would file the case? Ideally, it would be MHI’s call to action since it would be federal and nationally applied. It could be done.”

In a follow up from the same attorney, came this comment.

“It’s about time we looked at this as a viable legal option.”

Attorney Four statement included the following…

“…I do like the outside the box thinking on this. Very original…”

“I will say I also subscribe to the school of thought that there (are) multiple reasons for filing a law suit and only one of those is to win it. Profile. A suit does elevate the profile of an issue, so there could be some benefit there. “

All of the four attorneys asked gave cautionary notes as well as varying degrees of qualified to strong endorsements of the idea, as the samplings from the legal comments they made demonstrated.

At the end of the day, be it the industry seeking:

-

a Writ of Mandamus, or

-

the popular read and off the grid comments about MH Strikes suggested in this December column,

-

Other PR efforts,

-

all while pursing as a parallel path the passage of HR 1779 and S 1828,

clearly relief action on behalf of consumers and professionals by the manufactured housing industry is needed.

Perhaps some like minded group suffering from the above or a group of associations may decide to seek a Writ of Mandamus to compel certain acts such as the implementation of HERA 2008’s DTS or MHIA 2000. One thing is certain, 2014 is here and the time to act as the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau regulations kick that threaten sizable parts of manufactured housing lending is now. ##

The images above are from WikiCommons, and the image immediately above had this caption:

Pacific Rail Road Bond $1000 (No. 93) issued by the City & County of San Francisco (1865)

Source: The Cooper Collection of American Railroadiana

This Bond is one of the 400 issued to the Central Pacific Rail Road Company of California and 200 to the Western Pacific Rail Road Company in 1865 under the Act of the California Legislature passed on April 22, 1863 (as amended by Section Five of the “Compromise Act of April 4, 1864”), and approved by the electors of the City and County of San Francisco by a vote of 6,329 to 3,116 at a highly controversial (and subsequently litigated) Special Election held on Tuesday, May 19, 1863. The issuance of the Bonds was delayed for two years because the Mayor of San Francisco, Henry P. Coon, and then the County Clerk, Wilhelm Loewy, each refused to countersign the Bonds until ordered to do so by the Supreme Court of the State of California which granted Writs of Mandamus against Coon in 1864 (“The People of the State of California on the relation of the Central Pacific Railroad Company vs. Henry P. Coon, Mayor; Henry M. Hale, Auditor; and Joseph S. Paxson, Treasurer, of the City and County of San Francisco” (25 Cal 635) and Loewy in 1865 (“The People ex rel The Central Pacific Railroad Company of California vs.The Board of Supervisors of the City and County of San Francisco, and Wilhelm Lowey, Clerk” 27 Cal 655) directing that the Bonds be countersigned and delivered. All sixty of the interest coupons are attached to Bond #93 of which the first thirty-five had each been individually redeemed for semi-annual interest payments of $35.00. Coupon #1 was redeemed and cancelled on November 2, 1865, and coupon #35 on November 2, 1882, at which time the principal of $1,000.00 in gold coin was also paid from the Treasury of the City and County of San Francisco and the Bond was cancelled. ##

(Image credits, WikiCommons)

ManufacturedHomeLivingNews.com | MHProNews.com |

Business and Public Marketing & Ads: B2B | B2C

Websites, Contract Marketing & Sales Training, Consulting, Speaking:

MHC-MD.com | LATonyKovach.com | Office 863-213-4090

Connect on LinkedIN:

http://www.linkedin.com/in/latonykovach